History > Migration to Portland

Migration to Portland

The earliest groups of Volga German immigrants arrived in the United States in 1875 and 1876, settling primarily in Rush and Barton counties in Kansas and Franklin, Clay, and Hitchcock counties in Nebraska. All of these counties are near each other.

The early settlers suffered from drought and locusts, resulting in three years of crop failure. Their cattle were starving from lack of food and water on the range. The settlers also experienced tornados and severe electrical storms on the plains, which were uncommon in Russia. Some wrote about the heavy and persistent winds described as "unendurable" and the terrible conditions living in dugouts or sod houses. If all of this were not enough, the Nebraska group found their settlement was near the Great Western Cattle Trail, which was used to move long cattle drives from Texas to northeastern markets. During the drives, the Volga German settlers' fields and gardens were overrun by cattle. By 1880, many families decided it was time to look elsewhere.

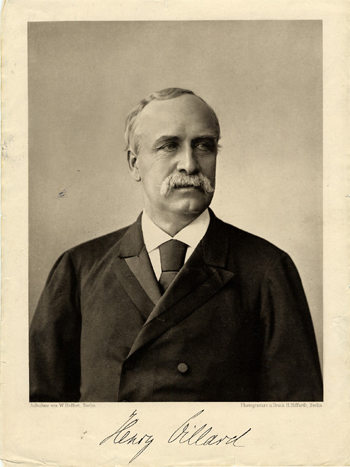

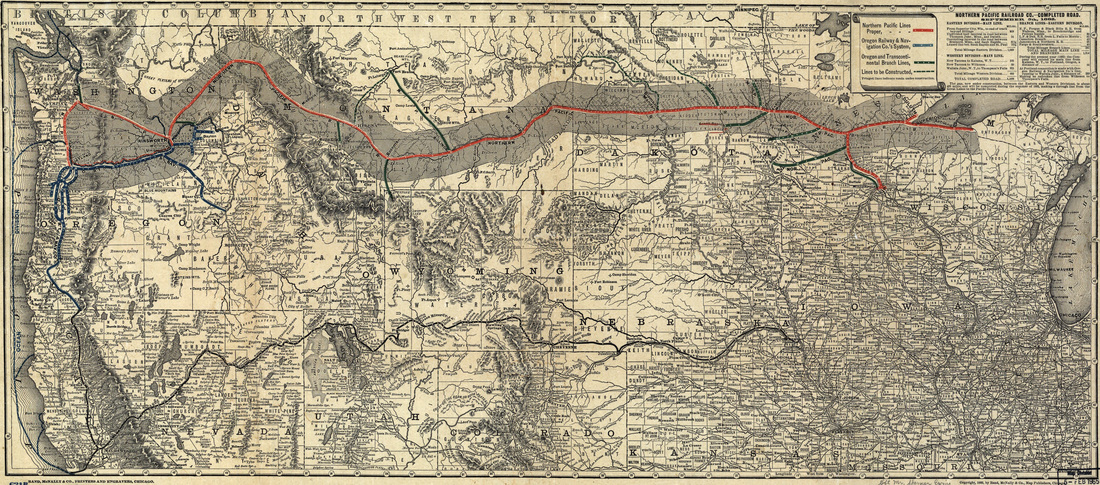

Groups from both Kansas and Nebraska were the first to migrate to Oregon in 1881 and 1882. The leaders of these groups were in contact with agents of Henry Villard's transportation and development companies. Villard, a German immigrant to the United States, was a pivotal figure in the growth and development of the Pacific Northwest. Villard's transportation companies, the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company (OR&N), Oregon Steam Navigation Company, and the Northern Pacific Railway, were principally responsible for the migration of the first Volga German settlers to the Pacific Northwest.

The early settlers suffered from drought and locusts, resulting in three years of crop failure. Their cattle were starving from lack of food and water on the range. The settlers also experienced tornados and severe electrical storms on the plains, which were uncommon in Russia. Some wrote about the heavy and persistent winds described as "unendurable" and the terrible conditions living in dugouts or sod houses. If all of this were not enough, the Nebraska group found their settlement was near the Great Western Cattle Trail, which was used to move long cattle drives from Texas to northeastern markets. During the drives, the Volga German settlers' fields and gardens were overrun by cattle. By 1880, many families decided it was time to look elsewhere.

Groups from both Kansas and Nebraska were the first to migrate to Oregon in 1881 and 1882. The leaders of these groups were in contact with agents of Henry Villard's transportation and development companies. Villard, a German immigrant to the United States, was a pivotal figure in the growth and development of the Pacific Northwest. Villard's transportation companies, the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company (OR&N), Oregon Steam Navigation Company, and the Northern Pacific Railway, were principally responsible for the migration of the first Volga German settlers to the Pacific Northwest.

Villard was designated "Oregon Commissioner of Immigration" in November of 1874 and set up offices in Boston, Omaha, and Topeka that worked in cooperation with the Northwest Immigration Bureau in Portland. Villard established the Oregon Improvement Company (OIC). Villard promoted Thomas R. Tannatt, a former advisor to President Abraham Lincoln, to serve as general agent of the OIC, and notable Portlanders C.H. Lewis, Henry Failing, C.J. Smith, J.N. Dolph, and C.H. Prescott were appointed as directors. In October 1880, the OIC purchased 150,000 acres in the heart of the Palouse country of Washington.

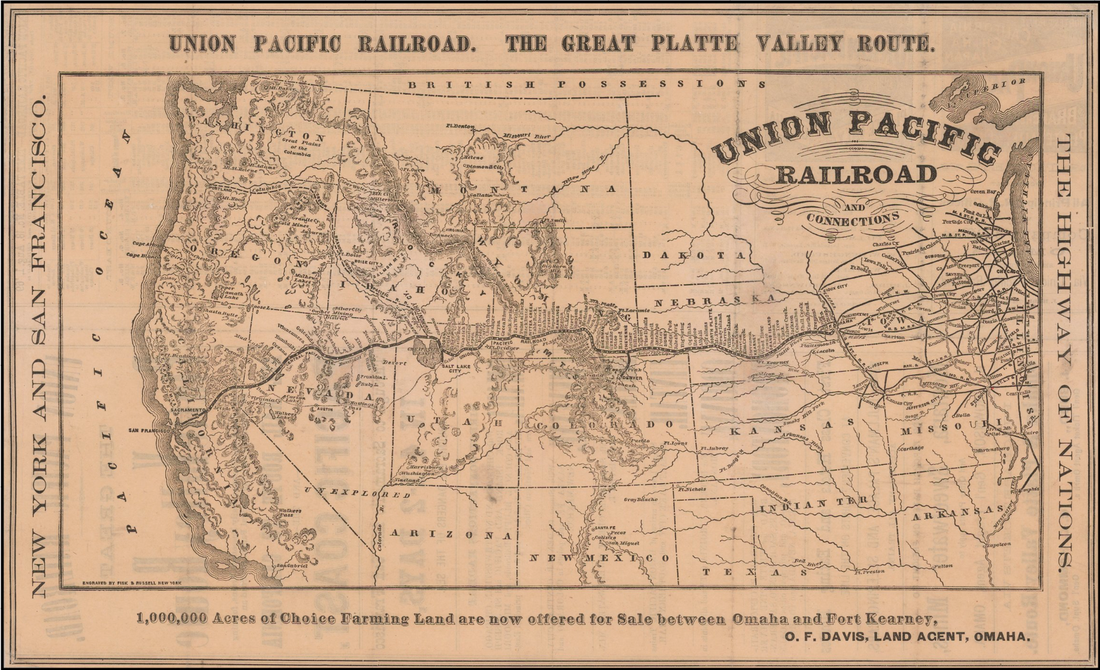

Men returning from railway survey work in the Pacific Northwest spoke to the settlers in the Midwest about the beautiful country and fertile land they had seen. Transportation companies such as the Union Pacific, Northern Pacific, and the OR&N soon provided favorable advertisements in German-language newspapers of the lush regions of the "Great Columbia Plain." They formed associations to offer reduced rates for those who wished to travel westward during the winter months. These companies hoped to profit from providing passenger services, tapping the immigrants as a labor source for constructing their railroads and as a market to sell their acreage. As the Oregon country developed, the railroads planned to benefit from the movement of people and commodities.

Freed from their five-year commitment under the Homestead Act and tempted by the promise of good farmland and jobs, many Volga Germans in Kansas and Nebraska looked favorably to the Pacific Northwest. The railroads benefited from laborers to help build and maintain the rail lines and infrastructure. These migrants would also settle on farmland acquired from the railroads. Shipment of their agricultural products to intended markets would depend on the railroads. It was a mutually beneficial arrangement.

Freed from their five-year commitment under the Homestead Act and tempted by the promise of good farmland and jobs, many Volga Germans in Kansas and Nebraska looked favorably to the Pacific Northwest. The railroads benefited from laborers to help build and maintain the rail lines and infrastructure. These migrants would also settle on farmland acquired from the railroads. Shipment of their agricultural products to intended markets would depend on the railroads. It was a mutually beneficial arrangement.

The Kansas Group

The Kansas contingent was the first to depart from the Midwest in 1881. The group included families from the Volga German colonies of Brunnental, Frank, Norka, Rosenfeld (a daughter colony of Norka), Neu-Yagodnaya Polyana, Schönfeld, and Schöntal. The last three were daughter colonies of Yagodnaya Polyana.

A contiguous rail line to Portland had yet to be completed. As a result, the Kansas party traveled on the Union Pacific Railroad to San Francisco.

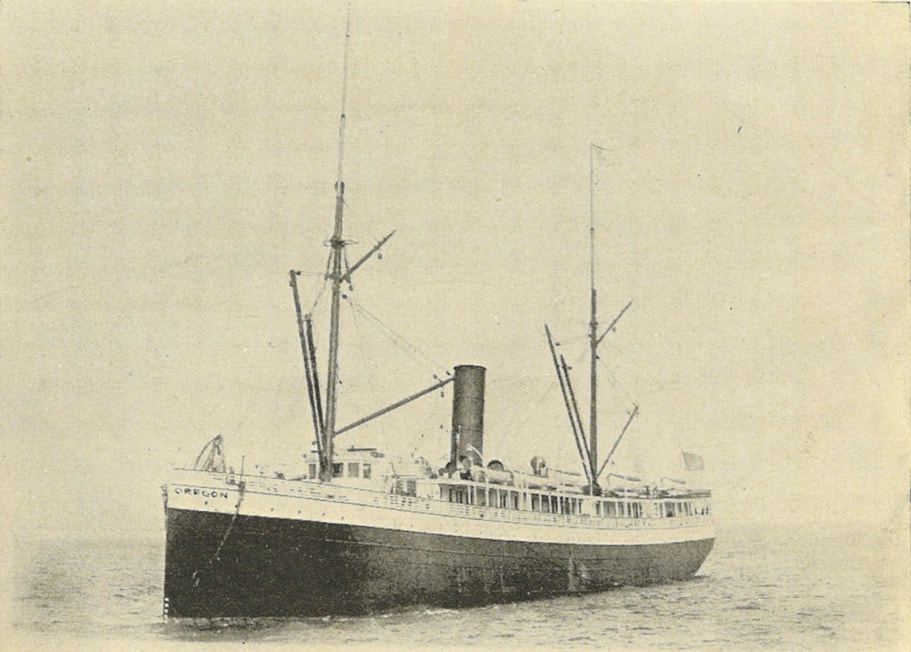

From San Francisco, the group sailed north aboard one of Villard's Oregon Steam and Navigation Company vessels, which touted service "every five days." The ship crossed the treacherous Columbia River bar and continued upriver to the confluence with the Willamette River and their final destination at the company docks in Portland.

The first Volga Germans to arrive in Portland from San Francisco possibly sailed on the "Steamer Oregon" (or a similar vessel) which was launched in 1878 and owned by the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company in 1881. Source: Photo of the "Steamer Oregon" in 1900 from a brochure titled "Seattle and the Orient" edited and compiled by Alfred D. Bowen. The photo is uncredited and in the public domain.

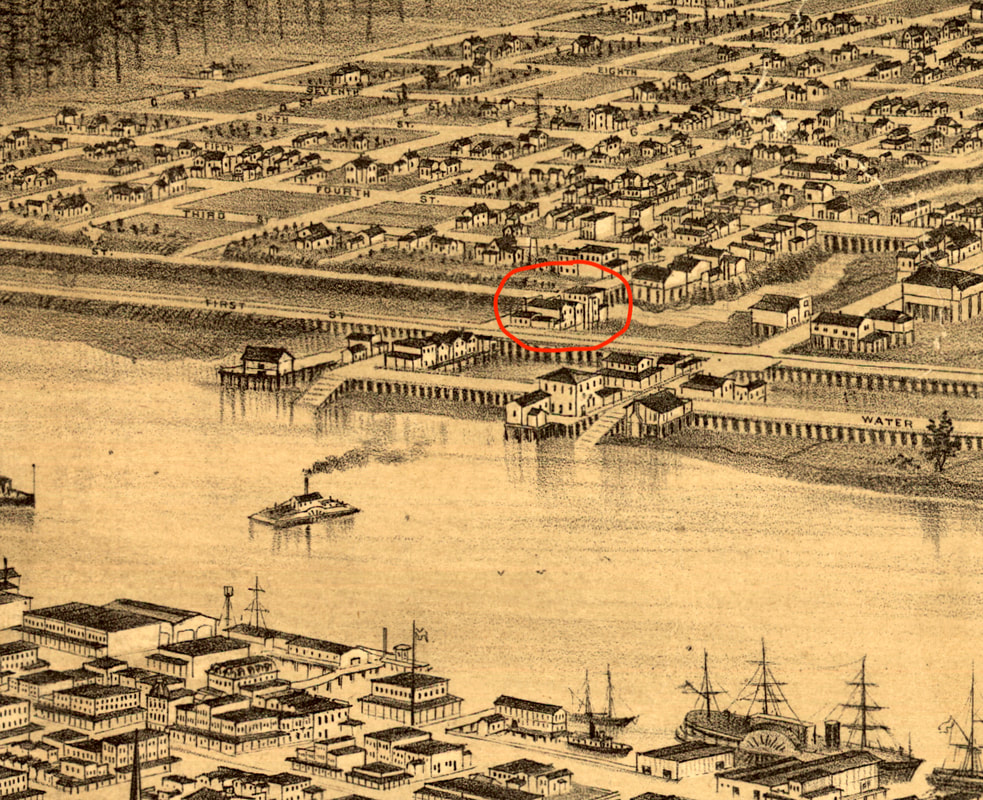

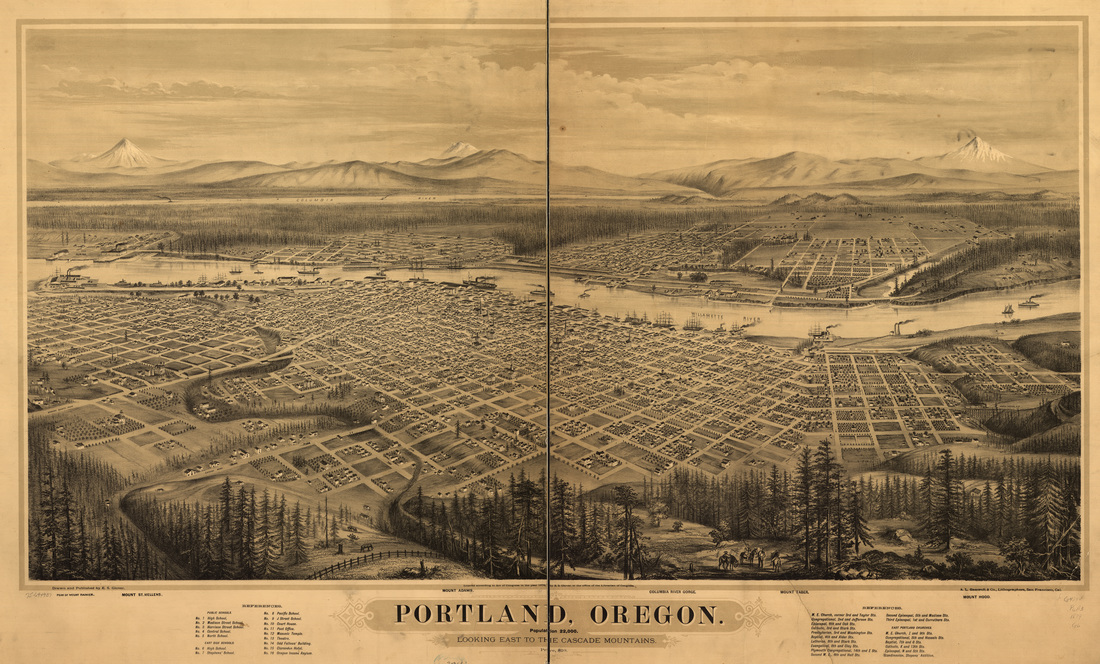

The Kansas group found temporary accommodation in East Portland, at that time an independent city. According to the 1882 Portland City Directory, most Kansas households apparently stayed at the Oriental Hotel, located near a ferry landing on the south side of J Street between First and Second (now SE Oak Street and SE 2nd Avenue). According to an 1878 advertisement published in The Oregonian, the hotel featured 12 sleeping rooms, a large sitting area, a dining room, and a kitchen.

The heads of the Volga German households were listed in the 1882 Portland City Directory as residents of the Oriental Hotel. This list of hotel residents was compiled by canvassers in the fall of 1881. The names represent the heads of household who occupied nearly all of the hotel's 12 sleeping rooms.

Some families, such as the Peter Ochs household, reportedly lived in houseboats or houses built atop pilings over the Willamette River. If so, they were not listed in the 1882 Albina or East Portland City Directories.

The heads of the Volga German households were listed in the 1882 Portland City Directory as residents of the Oriental Hotel. This list of hotel residents was compiled by canvassers in the fall of 1881. The names represent the heads of household who occupied nearly all of the hotel's 12 sleeping rooms.

- George Barth (listed as Bart)

- Henry Green (listed as Geine)

- John Helm

- Adam Hergert (listed as Herget)

- George Kleweno (listed as Kleaveno)

- John Kleweno (listed as Kleaveno)

- Philip Kleweno (listed as Kleaveno)

- John Ochs

- Adam Ruhl (listed as Ruhr)

- Conrad Schierman

- Henry Schierman

- John Schierman

- John Weigandt (listed as Viegand)

Some families, such as the Peter Ochs household, reportedly lived in houseboats or houses built atop pilings over the Willamette River. If so, they were not listed in the 1882 Albina or East Portland City Directories.

The men went to work at local sawmills and on the construction of the Albina fill project for the OR&N, which began in March 1882. The east Willamette waterfront was undergoing rapid industrial development at this time. The OR&N opened a gigantic 900-foot ocean shipping dock in 1882. In 1883, Plans were underway to construct a large consolidated rail works in Albina. William S. Ladd incorporated the Portland Flouring Mills. The seven-story mill was located near the rail yards and docks and became the largest mill in the Northwest.

Despite the abundance of work opportunities in Portland, the original intent of the Kansas group was to find prime farmland. To their disappointment, they soon discovered that much of the available land around Portland was heavily forested and unsuitable for their purpose. They were directed by officials of the Portland office of the OIC to consider settlement on land they had recently purchased in the Palouse country of Eastern Washington. Two scouts from the group, Phillip Green (the son of George Henry Green) and Peter Ochs (both conversant in English), were selected to view the area near the present-day town of Endicott. Thomas Tannatt hoped to sell them an entire township. Green and Ochs secured passes on the Union Pacific Railroad and traveled to Almota on the Snake River. From there, they went north to Colfax and to the present site of Endicott, which was undeveloped grassland then.

Green and Ochs observed that the land in this area was fertile and would make a very suitable home. The scouts quickly returned to Portland in late summer to organize their families and friends to move to the Palouse Country.

On a beautiful day in late September 1882, a group including members of the Green, Ochs, Litzenberger, and Batt families departed from East Portland aboard mule-drawn covered wagons. The weather on the Emigrant Road turned wet, snowy, and cold as they traveled to Walla Walla. On October 12th, the party arrived at the settlement site, pitched their tents, and began establishing homesteads.

Other party members departed from East Portland a few weeks later, traveling by rail to the terminus at Texas Ferry (now Ripiria, Washington) on the Snake River. This party was met by the group that had arrived earlier and by OIC teams who transported the new arrivals and their belongings to the settlement area. Some settlers lived in dugouts during the long, cold winter months. Some said it rained inside and outside - only a little longer inside.

A newspaper article published in The Oregonian's March 9, 1883 edition provides evidence that a few Kansas families remained at the Oriental Hotel in East Portland. The article describes a fire at the hotel the day before. It was noted that "through the exertions of the Russians who occupy the building, who rushed to the rescue with buckets of water, (the fire) did not spread beyond. The East Portland Fire Department will please take notice that no further danger is feared, and their services will not be needed. The Russians are ahead on 'first water' so far for the year 1883." Despite this report, no members of the Kansas party are found in the 1883 East Portland City Directory. The Oriental Hotel, which had opened in April 1871, again caught fire on May 1, 1883, and was presumed to be a total loss, according to the newspaper report.

Documents show that several households, including Philipp and Anna Margareth Hergert, Adam and Anna Maria Hergert, and Heinrich and Maria Elisabeth Scheuermann, remained in Oregon, where they found good farmland west of Portland near Cornelius. These families settled with other German immigrants and established the community of Blooming, Oregon. This community founded St. Peter's Lutheran Church.

George Henry and Anna Margaretha Green and many of their children moved to Silverton, Oregon, where they purchased 100 acres. George Henry established a store on his property. Initially, he named it Green’s Station, later changing it to Switzerland Station, likely due to the large number of immigrants from that country living there. George Henry would later return to Portland, operating a general store on Union Avenue.

All members of the Kansas party that permanently settled in Oregon were living in Rush County at the time of the 1880 U.S. Census.

Despite the abundance of work opportunities in Portland, the original intent of the Kansas group was to find prime farmland. To their disappointment, they soon discovered that much of the available land around Portland was heavily forested and unsuitable for their purpose. They were directed by officials of the Portland office of the OIC to consider settlement on land they had recently purchased in the Palouse country of Eastern Washington. Two scouts from the group, Phillip Green (the son of George Henry Green) and Peter Ochs (both conversant in English), were selected to view the area near the present-day town of Endicott. Thomas Tannatt hoped to sell them an entire township. Green and Ochs secured passes on the Union Pacific Railroad and traveled to Almota on the Snake River. From there, they went north to Colfax and to the present site of Endicott, which was undeveloped grassland then.

Green and Ochs observed that the land in this area was fertile and would make a very suitable home. The scouts quickly returned to Portland in late summer to organize their families and friends to move to the Palouse Country.

On a beautiful day in late September 1882, a group including members of the Green, Ochs, Litzenberger, and Batt families departed from East Portland aboard mule-drawn covered wagons. The weather on the Emigrant Road turned wet, snowy, and cold as they traveled to Walla Walla. On October 12th, the party arrived at the settlement site, pitched their tents, and began establishing homesteads.

Other party members departed from East Portland a few weeks later, traveling by rail to the terminus at Texas Ferry (now Ripiria, Washington) on the Snake River. This party was met by the group that had arrived earlier and by OIC teams who transported the new arrivals and their belongings to the settlement area. Some settlers lived in dugouts during the long, cold winter months. Some said it rained inside and outside - only a little longer inside.

A newspaper article published in The Oregonian's March 9, 1883 edition provides evidence that a few Kansas families remained at the Oriental Hotel in East Portland. The article describes a fire at the hotel the day before. It was noted that "through the exertions of the Russians who occupy the building, who rushed to the rescue with buckets of water, (the fire) did not spread beyond. The East Portland Fire Department will please take notice that no further danger is feared, and their services will not be needed. The Russians are ahead on 'first water' so far for the year 1883." Despite this report, no members of the Kansas party are found in the 1883 East Portland City Directory. The Oriental Hotel, which had opened in April 1871, again caught fire on May 1, 1883, and was presumed to be a total loss, according to the newspaper report.

Documents show that several households, including Philipp and Anna Margareth Hergert, Adam and Anna Maria Hergert, and Heinrich and Maria Elisabeth Scheuermann, remained in Oregon, where they found good farmland west of Portland near Cornelius. These families settled with other German immigrants and established the community of Blooming, Oregon. This community founded St. Peter's Lutheran Church.

George Henry and Anna Margaretha Green and many of their children moved to Silverton, Oregon, where they purchased 100 acres. George Henry established a store on his property. Initially, he named it Green’s Station, later changing it to Switzerland Station, likely due to the large number of immigrants from that country living there. George Henry would later return to Portland, operating a general store on Union Avenue.

All members of the Kansas party that permanently settled in Oregon were living in Rush County at the time of the 1880 U.S. Census.

The Nebraska Group

In 1880, a group in Culbertson, Nebraska, wrote to the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company (OR&N) in San Francisco, expressing their interest in moving 160 families to the "Washington Territory." Their letter was forwarded directly to Henry Villard.

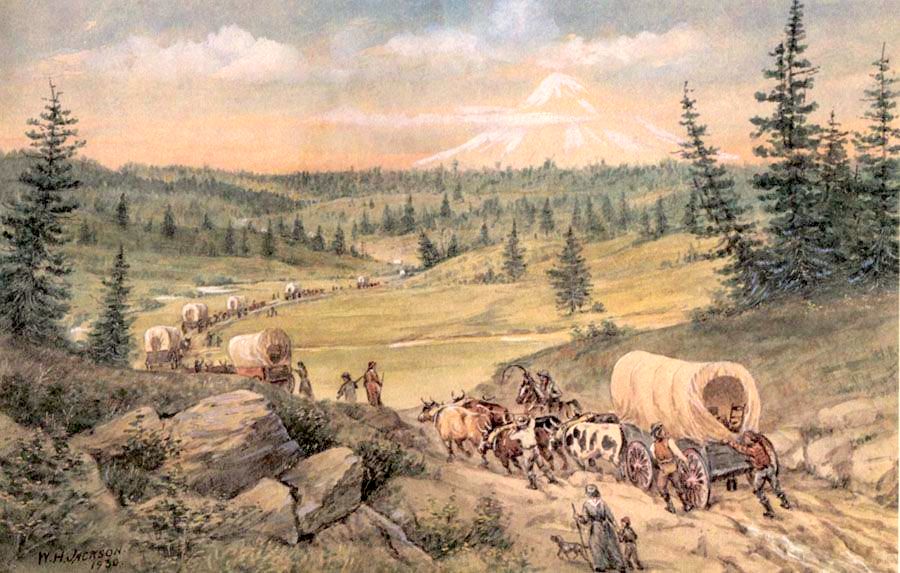

Although the Nebraska group had received a favorable response from the railroad officials in 1880, they delayed their decision to migrate to the Northwest until 1882. On March 17th, a caravan of 40 covered wagons, 28 of which belonged to Volga German families, began traveling west on the Oregon Trail along the Platte River. This was far less than the 160 families who indicated interest in 1880. There were 16 Volga German families from the colonies of Frank, Kolb, Messer, Norka, and Walter in the party. The Volga German families known to have been part of this group include Amen, Bastron, Bauer, Dewald, Kanzler, Kembel, Kiehn, Michel, Miller, Oestreich, Rosenoff, Schäfer, Schoessler, Theil, Wagner, and Wolsborn. The Thiel family alone had 4 wagons. Also traveling with the group was the Reverend F. Frucht.

Johann Frederich Rosenoff from the Volga German colony of Kolb was chosen as the group's leader. Johann Heinrich Oestreich and Georg Heinrich Kanzler were selected as scouts for locating the animals' water and pasture land. The group never traveled on Sundays, choosing to draw their wagons in a circle with lookouts posted as an elder read the church services in German. The Reverend Heinrich Franz Michel, born in the Volga German colony of Messer, Russia, served as minister to the party.

Upon arrival in North Platte, the party hired Union Pacific Railroad flatcars to transport them across the Rocky Mountains. All the wagons, animals, supplies, and people were loaded onto the railcars, which traveled to the end of the line at the Ogden, Utah station. The functional two-story wooden frame station was built in 1869 on a mud flat along the banks of the Weber River. In Ogden, the men worked to earn money for the next stage of their journey to Walla Walla, Washington.

Although the Nebraska group had received a favorable response from the railroad officials in 1880, they delayed their decision to migrate to the Northwest until 1882. On March 17th, a caravan of 40 covered wagons, 28 of which belonged to Volga German families, began traveling west on the Oregon Trail along the Platte River. This was far less than the 160 families who indicated interest in 1880. There were 16 Volga German families from the colonies of Frank, Kolb, Messer, Norka, and Walter in the party. The Volga German families known to have been part of this group include Amen, Bastron, Bauer, Dewald, Kanzler, Kembel, Kiehn, Michel, Miller, Oestreich, Rosenoff, Schäfer, Schoessler, Theil, Wagner, and Wolsborn. The Thiel family alone had 4 wagons. Also traveling with the group was the Reverend F. Frucht.

Johann Frederich Rosenoff from the Volga German colony of Kolb was chosen as the group's leader. Johann Heinrich Oestreich and Georg Heinrich Kanzler were selected as scouts for locating the animals' water and pasture land. The group never traveled on Sundays, choosing to draw their wagons in a circle with lookouts posted as an elder read the church services in German. The Reverend Heinrich Franz Michel, born in the Volga German colony of Messer, Russia, served as minister to the party.

Upon arrival in North Platte, the party hired Union Pacific Railroad flatcars to transport them across the Rocky Mountains. All the wagons, animals, supplies, and people were loaded onto the railcars, which traveled to the end of the line at the Ogden, Utah station. The functional two-story wooden frame station was built in 1869 on a mud flat along the banks of the Weber River. In Ogden, the men worked to earn money for the next stage of their journey to Walla Walla, Washington.

On May 20, 1882, the pioneers departed from Ogden and traveled on the California Trail to its junction with the Oregon Trail near the Snake River headwaters. In American Falls, Idaho. Here, the men were given temporary work constructing a new section of rail that would eventually pass through Boise, Idaho. Pleasant Valley, Oregon (arrived June 28, 1882), Baker City, Oregon and Pendleton, Oregon. In each frontier town, work was found, enabling them to earn money used to replenish supplies. The party reached Baker City on July 3, 1882, just in time for a Fourth of July celebration. When the party arrived in Pendleton, Oregon, most members decided to go on to Walla Walla, Washington, where they arrived on July 15th. A second part of the Nebraska group arrived in Walla Walla on August 20th. A handful of families remained in Baker City. They possibly wintered there, although some accounts state that they joined the group in Walla Walla in April of 1883.

Some families chose to remain in Walla Walla. Some families found work with Phillip Ritz, the founder of Ritzville, who encouraged them to consider his settlement. In 1883, many people did. Ritzville consisted of a railroad depot, a storage shed, and about 60 people. A metal wagon trail sculpture in Ritzville commemorates their pioneering journey.

Some families chose to remain in Walla Walla. Some families found work with Phillip Ritz, the founder of Ritzville, who encouraged them to consider his settlement. In 1883, many people did. Ritzville consisted of a railroad depot, a storage shed, and about 60 people. A metal wagon trail sculpture in Ritzville commemorates their pioneering journey.

Although many in the Nebraska party decided to settle in Walla Walla or Ritzville, a small number of families chose to continue to Portland. Continuing their journey by covered wagon over the Oregon Trail, the party had to decide how to pass through the Cascade Mountain Range when the Oregon Trail ended at The Dalles. The OR&NC rail line from Wallula Junction to Portland was not fully completed then. Ironically, the line was finished just months later, on November 20, 1882. There were two possible routes leading to Portland. The first route avoided the treacherous Columbia River cascades by traveling over the Barlow Road from The Dalles, around the south side of Mt. Hood, to the town of Sandy. From Sandy, they departed from the Barlow Road and followed Sandy Road (now Highway 26 and Sandy Boulevard) into Portland.

The second option was to continue down the Columbia River using the Oregon Steam Navigation Company system of sternwheelers and portage railroads. Which route the Nebraska pioneers chose is not known.

It was late summer or early fall of 1882 when the small splinter group from Kansas became the first Volga Germans to arrive in Portland.

Two Nebraska households are listed in the 1883 Portland, East Portland, and Albina City Directory, likely compiled in the winter of 1882. The Ludwig and Emma Yost family and the Johannes and Anna Maria Schnell family lived in the Albina Township near the intersection of Woods Street and Page Street (now approximately N. Albina Avenue and N. Page Street).

While they are not listed in the 1883 city directories, other evidence indicates that the Ludwig and Anna Elisabeth Spady, Conrad and Sophia Schwartz, Heinrich and Elisabeth Schreiber, and the George and Elisabeth Schreiber families arrived with the Nebraska group in 1882. These families settled in Albina except for the Schreiber's, who initially settled in rural Washington County near the Kansas families. Most of the Schreiber family later moved from the farm to Albina. It should be noted that the Conrad and Sophia Schwartz family lived in Kellogg, Iowa, in 1880 and likely had family ties to the Nebraska group through her Trüber family.

All of the Nebraska families listed above migrated from Norka, Russia, and may have known each other before they migrated to America. The Schnell, Schreiber, and Spady families lived adjacent to each other in Franklin County, Nebraska, in 1880.

Two Nebraska households are listed in the 1883 Portland, East Portland, and Albina City Directory, likely compiled in the winter of 1882. The Ludwig and Emma Yost family and the Johannes and Anna Maria Schnell family lived in the Albina Township near the intersection of Woods Street and Page Street (now approximately N. Albina Avenue and N. Page Street).

While they are not listed in the 1883 city directories, other evidence indicates that the Ludwig and Anna Elisabeth Spady, Conrad and Sophia Schwartz, Heinrich and Elisabeth Schreiber, and the George and Elisabeth Schreiber families arrived with the Nebraska group in 1882. These families settled in Albina except for the Schreiber's, who initially settled in rural Washington County near the Kansas families. Most of the Schreiber family later moved from the farm to Albina. It should be noted that the Conrad and Sophia Schwartz family lived in Kellogg, Iowa, in 1880 and likely had family ties to the Nebraska group through her Trüber family.

All of the Nebraska families listed above migrated from Norka, Russia, and may have known each other before they migrated to America. The Schnell, Schreiber, and Spady families lived adjacent to each other in Franklin County, Nebraska, in 1880.

From Small Beginnings

By the end of 1882, approximately 17 Volga German adults and children lived in Albina. About another 28 people lived in rural Washington County, and 9 people lived in rural Marion County. In total, about 54 Volga Germans were the small beginnings of a group that would grow much larger in the years to come.

Subsequent Arrivals 1883-1892

Villard's Northern Pacific Railway celebrated the first transcontinental train to arrive in Portland on September 11, 1883, about a year after the Nebraska party had arrived. The last section of the line initially utilized the OR&N track on the south side of the Columbia River to pass through the Cascades (see the blue line on the map below). Later, it used the northerly route from Wallula Junction to Tacoma and then turned south to Portland (see the red line in the map below).

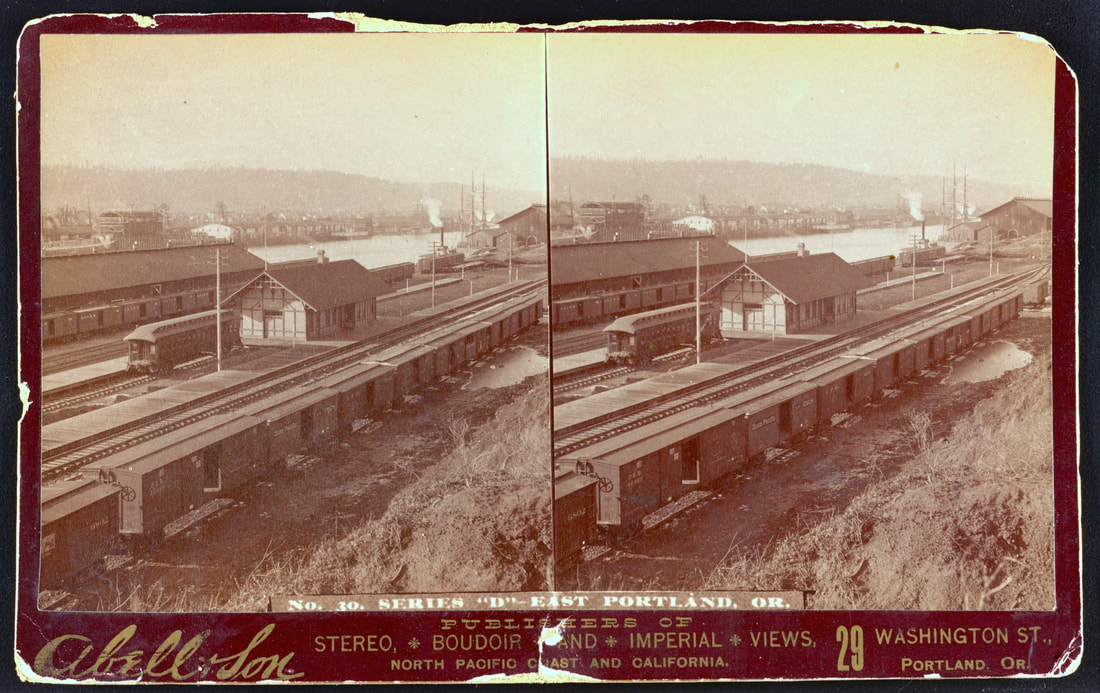

The triumphal completion of the transcontinental railroad opened the door for further migration. However, only a small number of Volga German pioneers initially followed the first two groups and settled in Portland between 1883 and 1889. During this period, those arriving by train disembarked at Portland's first passenger Union Depot, a humble wood structure building in East Portland near the east end of today's Steel Bridge. Today's Union Station, located on the west bank of the Willamette River, did not open until 1896.

Stereographic photo of the earliest train station built in East Portland, at the foot of Cedar Street, in the summer of 1883 at a cost $5,000. Union Station, located on the west bank of the Willamette River, opened in 1896. Source: Library of Congress (LCCN Permalink

https://lccn.loc.gov/2018652458).

Most Volga Germans who settled in Portland from 1883 until 1892 were from the colony of Norka, Russia. Many of these households were interconnected by a network of family relationships.

Letters were written to family members and friends living in Russia and the Midwest, encouraging them to come to Portland, where jobs and housing were readily available. As a result, larger groups of Volga Germans arrived in Portland between 1890 and 1895. Historian Richard Sallet documented that a group of Catholic Volga Germans from the colonies of Köhler and Semenovka arrived in Portland in 1892.

Migration from Russia during this time can also be attributed to the banning of the Brethren movement in Russia in 1888 and the disastrous Russian famine of 1891-1892, which hit the Volga region particularly hard.

One of the early settlers, Gottfried Geist from Kraft, Russia, provided a colorful recollection of the early settlement during an oral interview conducted by Wanda June Schwabauer:

"There was a large group in the early days. Some people lived down on the Willamette River in houseboats. Flooding wiped them out and they moved to the Albina area along Union Avenue. Mr. Geist said he would live anywhere but San Francisco."

Mr. Geist was likely referring to the great flood of 1894, which devastated the Portland area and Willamette Valley. Apparently, he traveled to Portland from San Francisco via steamship, much like the Kansas group in 1881.

The Volga Germans were not the first Germans to arrive in Portland. Germans were already one of the largest foreign-born ethnic groups in Portland by 1881. In 1870, it was estimated that 30 percent of Portland's business owners were Germans. Many prominent citizens included Henry Villard, Henry Weinhard, Henry Wemme, Frank Dekum, Jacob Kamm, Henry Saxer, and Louis Nicolai. Two men of German-Jewish descent, Bernard Goldsmith and Philip Wasserman, served as mayor of Portland between 1869 and 1873. Despite sharing elements of language and culture, the Volga Germans were viewed by immigrants from the German empire and other ethnic groups as either "Russians" or not wholly German. As they had done in Russia, the Volga Germans formed their own community with a shared language, culture, and religious beliefs. They tended not to attend churches or socialize with Germans who had come directly from Western Europe.

Many factors influenced the first Volga Germans to settle in Albina rather than other parts of Portland. At the time, Albina was essentially a company town, the company being the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company, which owned the extensive Albina railroad yards, car shops, and docks along the east side of the Willamette River. The Northern Pacific Railroad, completed two years after the first Volga Germans arrived, terminated their passenger service in East Portland. At the time, access to Portland on the west side of the river was by ferry only. Much of the productive farmland in the Portland area had already been claimed in prior decades, leaving the Volga Germans to seek work in the city. Land in the newly developing Albina area (which did not become a city until 1887) was relatively inexpensive to purchase, and it was very close to the railway workshops where many early immigrants found employment.

Since Albina was a very lightly populated area in the early 1880s (143 people in 1880), most people could build homes and live together as they had in Russia. Living in close proximity allowed the Volga Germans to maintain their language, culture, and identity in a new land. Establishing churches and businesses to serve the community was also made easier, given the compact nature of the settlement. This group of pioneers in Portland would grow to over 500 families by 1920.

Many factors influenced the first Volga Germans to settle in Albina rather than other parts of Portland. At the time, Albina was essentially a company town, the company being the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company, which owned the extensive Albina railroad yards, car shops, and docks along the east side of the Willamette River. The Northern Pacific Railroad, completed two years after the first Volga Germans arrived, terminated their passenger service in East Portland. At the time, access to Portland on the west side of the river was by ferry only. Much of the productive farmland in the Portland area had already been claimed in prior decades, leaving the Volga Germans to seek work in the city. Land in the newly developing Albina area (which did not become a city until 1887) was relatively inexpensive to purchase, and it was very close to the railway workshops where many early immigrants found employment.

Since Albina was a very lightly populated area in the early 1880s (143 people in 1880), most people could build homes and live together as they had in Russia. Living in close proximity allowed the Volga Germans to maintain their language, culture, and identity in a new land. Establishing churches and businesses to serve the community was also made easier, given the compact nature of the settlement. This group of pioneers in Portland would grow to over 500 families by 1920.

Sources

Eastwood, Harland. Herr Kanzler's Kinder. Harland Eastwood Publishing. 2006.

Craighead, Alexander B. Railway Palaces of Portland, Oregon. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2016. Print.

Galbraith, Jean and Schwisow, Joan. Obituaries of the Volga Germans on the 1882 Wagon Train. May 1998.

Green, Josie. History of the Rothe and Green Families. N.d.

Kelley, Barbara Camp. "Information about Phillip Green and Anna Rothe." Telephone interview. Aug. 2016. Barbara Camp Kelley (Milwaukie, Oregon) is the Great-granddaughter of Phillip Green and Anna Rothe.

Haynes, Emma S. My Mother's People. N.p.: 1959. Print.

Killen, John. "Past Tense Oregon: Vintage 1894 photos show floods nothing new to Portland." OregonLive, 09 Feb. 2015.

Klaus, Lois. "The Wagon Train". AHSGR Oregon Chapter Newsletter. Vol. 20. No. 6. November/December 1999.

Ochs, Grace Lillian. Up from the Volga; the Story of the Ochs Family. Nashville: Southern Pub. Association, 1969. Print.

Rath, George. Emigration from Germany through Poland and Russia to the U.S.A. Salt Lake City, UT: Genealogical Society of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1969. Print.

Robertson, Donald B. Encyclopedia of Western Railroad History: Volume III Oregon Washington. Caldwell, ID: Caxton Printers, 1995. Print.

Sallet, Richard. Russian-German Settlements in the United States. Fargo: North Dakota Institute for Regional Studies, 1974. Print.

Scheuerman, Richard D., and Clifford E. Trafzer. The Volga Germans: Pioneers of the Northwest. Moscow, ID: University of Idaho, 1980. Print.

Scheuerman, Richard D., and Clifford E. Trafzer. Hardship to Homeland Pacific Northwest Volga Germans. Pullman, WA: Washington State UP, 2018. Print.

Scheuerman, Richard D. "From Wagon Trails to Iron Rails: Russian German Immigration to the Pacific Northwest." Journal of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia 2.2 (1979): 37. Print.

Schwabauer, Wanda J. "The Portland Community of Germans from Russia." Diss. Portland State U, 1974. Print.

Tannatt, T.R. Correspondence of T.R. Tannatt, General Eastern Passenger and Immigration Agent, New York, mostly to Henry Villard, President.

Originals at: Harvard University Library. Photostatic copies. Washington State University Libraries.

Weitz, Anna Green. "Story of a Pioneer." Ed. P. D. Niles. Endicott Index [Endicott, Washington] 29 Nov. 1935: n. pag. Print.

Portland City Directory 1882. Embracing a Residence Directory of Portland and East Portland. Portland, Oregon. J.K. Gill & Co. 1 March 1882.

"Business Notices" The Oregonian [Portland], April 13, 1871.

"The O. R. and N. Co.'s Terminus. Work At Albina To Be Commerced Next Week". The Morning Oregonian [Portland], March 8, 1882.

"Northern Pacific Depot". The Morning Oregonian [Portland}, October 7, 1882, page 3.

"Albina. The Actual Terminus of Our Railway System." The Sunday Oregonian [Portland}. November 26, 1882, page 5.

"East Portland. Union Depot" The Morning Oregonian [Portland], July 16, 1883, page 5.

"From Last Spike to Portland" The Morning Oregonian [Portland}. September 11, 1883, pages 1, 3 and 4.

"The East Side. Fire". The Oregonian [Portland], March 9, 1883,

"East Portland Fire." The Morning Oregonian [Portland], May 1, 1883.

Obituary for Phillip Green, The Otis Reporter, Otis, Rush County, Kansas, Friday, August 28, 1914, Volume 3, Number 13, Page 1.

Craighead, Alexander B. Railway Palaces of Portland, Oregon. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2016. Print.

Galbraith, Jean and Schwisow, Joan. Obituaries of the Volga Germans on the 1882 Wagon Train. May 1998.

Green, Josie. History of the Rothe and Green Families. N.d.

Kelley, Barbara Camp. "Information about Phillip Green and Anna Rothe." Telephone interview. Aug. 2016. Barbara Camp Kelley (Milwaukie, Oregon) is the Great-granddaughter of Phillip Green and Anna Rothe.

Haynes, Emma S. My Mother's People. N.p.: 1959. Print.

Killen, John. "Past Tense Oregon: Vintage 1894 photos show floods nothing new to Portland." OregonLive, 09 Feb. 2015.

Klaus, Lois. "The Wagon Train". AHSGR Oregon Chapter Newsletter. Vol. 20. No. 6. November/December 1999.

Ochs, Grace Lillian. Up from the Volga; the Story of the Ochs Family. Nashville: Southern Pub. Association, 1969. Print.

Rath, George. Emigration from Germany through Poland and Russia to the U.S.A. Salt Lake City, UT: Genealogical Society of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1969. Print.

Robertson, Donald B. Encyclopedia of Western Railroad History: Volume III Oregon Washington. Caldwell, ID: Caxton Printers, 1995. Print.

Sallet, Richard. Russian-German Settlements in the United States. Fargo: North Dakota Institute for Regional Studies, 1974. Print.

Scheuerman, Richard D., and Clifford E. Trafzer. The Volga Germans: Pioneers of the Northwest. Moscow, ID: University of Idaho, 1980. Print.

Scheuerman, Richard D., and Clifford E. Trafzer. Hardship to Homeland Pacific Northwest Volga Germans. Pullman, WA: Washington State UP, 2018. Print.

Scheuerman, Richard D. "From Wagon Trails to Iron Rails: Russian German Immigration to the Pacific Northwest." Journal of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia 2.2 (1979): 37. Print.

Schwabauer, Wanda J. "The Portland Community of Germans from Russia." Diss. Portland State U, 1974. Print.

Tannatt, T.R. Correspondence of T.R. Tannatt, General Eastern Passenger and Immigration Agent, New York, mostly to Henry Villard, President.

Originals at: Harvard University Library. Photostatic copies. Washington State University Libraries.

Weitz, Anna Green. "Story of a Pioneer." Ed. P. D. Niles. Endicott Index [Endicott, Washington] 29 Nov. 1935: n. pag. Print.

Portland City Directory 1882. Embracing a Residence Directory of Portland and East Portland. Portland, Oregon. J.K. Gill & Co. 1 March 1882.

"Business Notices" The Oregonian [Portland], April 13, 1871.

"The O. R. and N. Co.'s Terminus. Work At Albina To Be Commerced Next Week". The Morning Oregonian [Portland], March 8, 1882.

"Northern Pacific Depot". The Morning Oregonian [Portland}, October 7, 1882, page 3.

"Albina. The Actual Terminus of Our Railway System." The Sunday Oregonian [Portland}. November 26, 1882, page 5.

"East Portland. Union Depot" The Morning Oregonian [Portland], July 16, 1883, page 5.

"From Last Spike to Portland" The Morning Oregonian [Portland}. September 11, 1883, pages 1, 3 and 4.

"The East Side. Fire". The Oregonian [Portland], March 9, 1883,

"East Portland Fire." The Morning Oregonian [Portland], May 1, 1883.

Obituary for Phillip Green, The Otis Reporter, Otis, Rush County, Kansas, Friday, August 28, 1914, Volume 3, Number 13, Page 1.

Last updated October 26, 2023