Community > Characteristics

Characteristics

There are several characteristics of the Volga German ethnic group that allow us to uniquely identify it from the time of their first arrival in 1881 up to the 1940s and 1950s when assimilation and dispersion broke down the community.

The Volga Germans were accustomed to living as a minority surrounded by a much larger majority. Far from their ancestral homeland in Germany and Western Europe, the Volga Germans evolved as an isolated group whose language, traditions, and beliefs separated them from the larger Russian population. They become comfortable living outside the mainstream in mostly self-supporting communities. They saw themselves as different from their neighbors.

The community in Portland began as if another colony were being formed in Albina. Most early pioneers came from the same colony of Norka, Russia. They chose to live in the same part of NE Portland, went to churches formed by Volga Germans, shopped in stores owned by Volga Germans, and generally married within the ethnic group. The clannish behavior common in Russia, was transferred to the new settlements in North America. Few outsiders clearly identified the Volga Germans as a distinct ethnic group. The Volga Germans kept to themselves and preferred a low profile, especially during the two world wars when people did not differentiate between Russian Germans and the Germans of imperial or fascist Germany. Although a few historical works, such as Kimbark MacColl's The Shaping of City, correctly locate the ethnic group on a map, the history of the Volga Germans in Portland, and more broadly in Oregon, has been largely overlooked by historians who are simply unaware of its existence. The Volga Germans, content to be "under the radar," did little to raise their profile in the broader community.

The Volga Germans were accustomed to living as a minority surrounded by a much larger majority. Far from their ancestral homeland in Germany and Western Europe, the Volga Germans evolved as an isolated group whose language, traditions, and beliefs separated them from the larger Russian population. They become comfortable living outside the mainstream in mostly self-supporting communities. They saw themselves as different from their neighbors.

The community in Portland began as if another colony were being formed in Albina. Most early pioneers came from the same colony of Norka, Russia. They chose to live in the same part of NE Portland, went to churches formed by Volga Germans, shopped in stores owned by Volga Germans, and generally married within the ethnic group. The clannish behavior common in Russia, was transferred to the new settlements in North America. Few outsiders clearly identified the Volga Germans as a distinct ethnic group. The Volga Germans kept to themselves and preferred a low profile, especially during the two world wars when people did not differentiate between Russian Germans and the Germans of imperial or fascist Germany. Although a few historical works, such as Kimbark MacColl's The Shaping of City, correctly locate the ethnic group on a map, the history of the Volga Germans in Portland, and more broadly in Oregon, has been largely overlooked by historians who are simply unaware of its existence. The Volga Germans, content to be "under the radar," did little to raise their profile in the broader community.

A common German dialect created the strongest bond. This was not modern German but an old Hessian dialect carried to Russia by the colonists who settled there in the mid-1760s. Immigrants from Germany often did not consider the Volga Germans as fellow Germans. They considered them Russians - a designation the Volga Germans did not warmly embrace. As a result, there seems to have been only limited interaction between the two German ethnic groups.

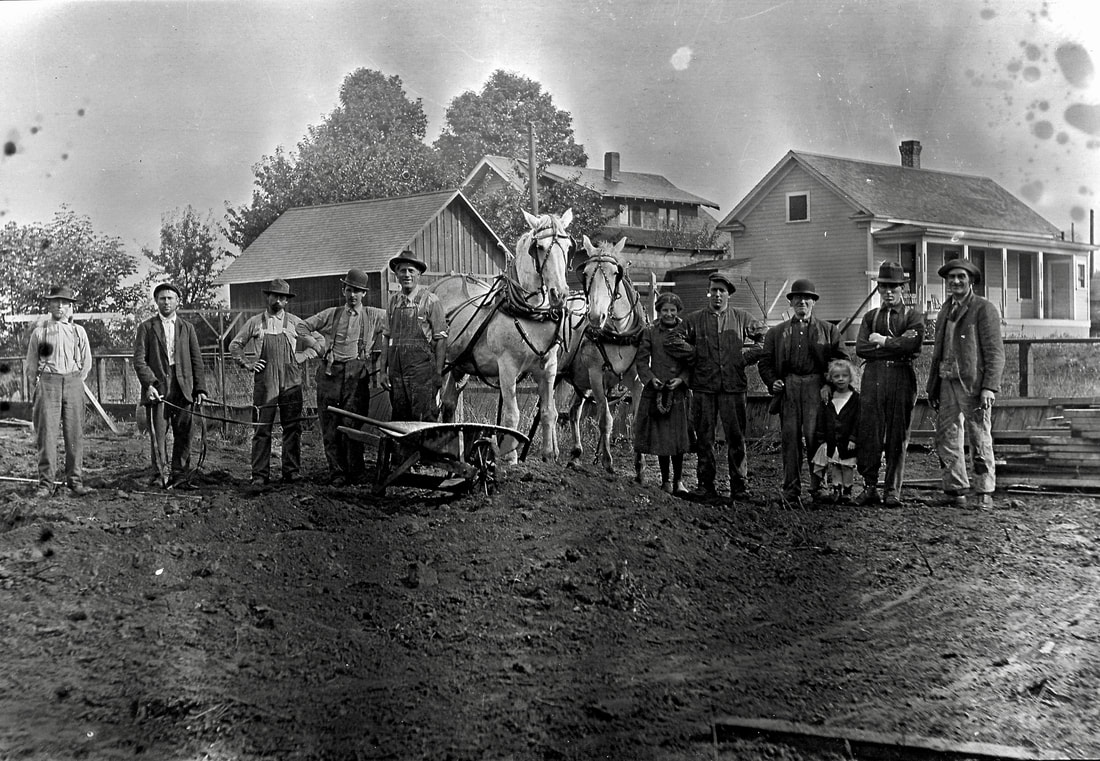

In the early decades of settlement in Portland, families were often large, as in Russia. It was not uncommon to have ten or more people in a single-family unit. Aging parents usually lived with one of their children. In preindustrial agricultural societies, children were a valuable, productive asset – even six-year-olds could carry out essential household tasks. In Russia, the need for helping hands and a lack of modern contraceptives led to large families despite relatively high infant mortality rates. As the community transitioned to an urban and industrial society in America, family sizes decreased over time.

Religious beliefs and practices were another vital element that bonded the community together. Most people attended church as it was not only the source of spiritual life but also served an equally important role as the center of social life.

Skepticism about the government was common. Given their sometimes unhappy experiences as subjects of German nobility and in Russia living under numerous Czar's, there was inbred distrust of officials and those in power. The Volga Germans typically did not engage in political activity.

In the early years, the Volga Germans wore traditional clothing typical to their lives on the Russian steppe. Women in black or brown shawls could be seen in the neighborhood or gathered outside the church on Sunday. The men more readily assimilated their clothing as they worked with people from other ethnic groups where conformity was more important than tradition. The temperate climate of Portland made heavy sheepskin jackets and felt or leather boots unnecessary.

The Volga Germans were typically very frugal. They bought or built their modest cottage homes in Albina and generally paid in cash. Richard Sallet states that based on the 1920 U.S. Census, over 95 percent of the Volga Germans residing in Portland owned their homes. Whatever the income level, it was always important to maintain your home and yard well.

In the early decades of settlement in Portland, families were often large, as in Russia. It was not uncommon to have ten or more people in a single-family unit. Aging parents usually lived with one of their children. In preindustrial agricultural societies, children were a valuable, productive asset – even six-year-olds could carry out essential household tasks. In Russia, the need for helping hands and a lack of modern contraceptives led to large families despite relatively high infant mortality rates. As the community transitioned to an urban and industrial society in America, family sizes decreased over time.

Religious beliefs and practices were another vital element that bonded the community together. Most people attended church as it was not only the source of spiritual life but also served an equally important role as the center of social life.

Skepticism about the government was common. Given their sometimes unhappy experiences as subjects of German nobility and in Russia living under numerous Czar's, there was inbred distrust of officials and those in power. The Volga Germans typically did not engage in political activity.

In the early years, the Volga Germans wore traditional clothing typical to their lives on the Russian steppe. Women in black or brown shawls could be seen in the neighborhood or gathered outside the church on Sunday. The men more readily assimilated their clothing as they worked with people from other ethnic groups where conformity was more important than tradition. The temperate climate of Portland made heavy sheepskin jackets and felt or leather boots unnecessary.

The Volga Germans were typically very frugal. They bought or built their modest cottage homes in Albina and generally paid in cash. Richard Sallet states that based on the 1920 U.S. Census, over 95 percent of the Volga Germans residing in Portland owned their homes. Whatever the income level, it was always important to maintain your home and yard well.

Street-cars were seldom used, because the five cent fare was considered too expensive. -- Emma Schwabenland Haynes

Reusing household items, composting, making their own clothes, and patching worn clothing were all common practices. Many people had their own gardens and fruit trees. Canning and pickling food was the norm. Many people also kept a few chickens for eggs and meat. A practice that's again become popular in Portland!

Many recall the annual ritual of transporting and stacking 10 to 12 cords of wood, which was moved from the curb to the basement, where it fueled a wood stove during the winter. The work often started in March and continued through August.

Hard work was one of the preeminent characteristics of the group. In the early years, advanced education was not highly valued. The women worked to maintain the household and often held jobs working as domestics or as laborers in factories. The men worked in the rail yards, street maintenance, collecting garbage, and other physical jobs. They lived by their motto, "Arbeit macht das Lebens süss" or "Work makes life sweet."

After escaping war, poverty, and famine in Germany during the 1760s and a century later fleeing from many of the same horrors in Russia, the Volga Germans indeed found Portland a sweet place to call home.

Hard work was one of the preeminent characteristics of the group. In the early years, advanced education was not highly valued. The women worked to maintain the household and often held jobs working as domestics or as laborers in factories. The men worked in the rail yards, street maintenance, collecting garbage, and other physical jobs. They lived by their motto, "Arbeit macht das Lebens süss" or "Work makes life sweet."

After escaping war, poverty, and famine in Germany during the 1760s and a century later fleeing from many of the same horrors in Russia, the Volga Germans indeed found Portland a sweet place to call home.

Sources

Brill, Conrad. "Memories of Norka." Journal of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia 8.2 (1985): 1-16. Web. 30 Mar. 2016.

Haynes, Emma S. My Mother's People. N.p.: 1959. Print.

MacColl, E. Kimbark. The Shaping of a City: Business and Politics in Portland, Oregon, 1885-1915. Portland, Or.: Georgian, 1976. Print.

Sallet, Richard. Russian-German Settlements in the United States. Fargo: North Dakota Institute for Regional Studies, 1974. Print.

Scheuerman, Richard D., and Clifford E. Trafzer. The Volga Germans: Pioneers of the Northwest. Moscow, ID: U of Idaho, 1980. Print.

Haynes, Emma S. My Mother's People. N.p.: 1959. Print.

MacColl, E. Kimbark. The Shaping of a City: Business and Politics in Portland, Oregon, 1885-1915. Portland, Or.: Georgian, 1976. Print.

Sallet, Richard. Russian-German Settlements in the United States. Fargo: North Dakota Institute for Regional Studies, 1974. Print.

Scheuerman, Richard D., and Clifford E. Trafzer. The Volga Germans: Pioneers of the Northwest. Moscow, ID: U of Idaho, 1980. Print.

Last updated October 21, 2023