History > World War I

World War I

The outbreak of World War I on July 28, 1914, was met with anxiety and fear by the Volga German colonists living in Russia and their family and friends who had immigrated to the United States.

The war exacerbated Russia’s Germanophobia and Slavophile tendencies. Even though the Volga Germans had lived peacefully in Russia for 150 years, Russian Foreign Minister Zazonov called for a “final solution” to the ethnic German problem in Russia, noting that the time had come "...to deal with this long over-due problem, for the current war has created the conditions to make it possible to solve this problem once and for all.” Russian General Polivanov wrote in a pamphlet that was distributed among Russian soldiers on the order of Grand Duke Nicholas, the Tsar's uncle:

The war exacerbated Russia’s Germanophobia and Slavophile tendencies. Even though the Volga Germans had lived peacefully in Russia for 150 years, Russian Foreign Minister Zazonov called for a “final solution” to the ethnic German problem in Russia, noting that the time had come "...to deal with this long over-due problem, for the current war has created the conditions to make it possible to solve this problem once and for all.” Russian General Polivanov wrote in a pamphlet that was distributed among Russian soldiers on the order of Grand Duke Nicholas, the Tsar's uncle:

"Russia's Germans must all be driven out, without respect of age, sex, any supposed usefulness, or their many years of residence in the empire."

Despite their loyalty to Russia, the following insult was not uncommon:

"You are Germans--Nemski," they were charged. We are going to fight the barbarians, your brothers. Woe to you, you scoundrels, if you make any effort to help your Kaiser Wilhelm."

Despite the rhetoric, thousands of Volga German men were conscripted to serve in the Russian military. However, they were not allowed to speak German or sing German songs. They were watched closely as if they were the enemy. Their situation worsened in 1915 after the German forces' major defeat of the Russian army. Without evidence, the ethnic Germans serving in the Russian army were conveniently blamed for the defeat.

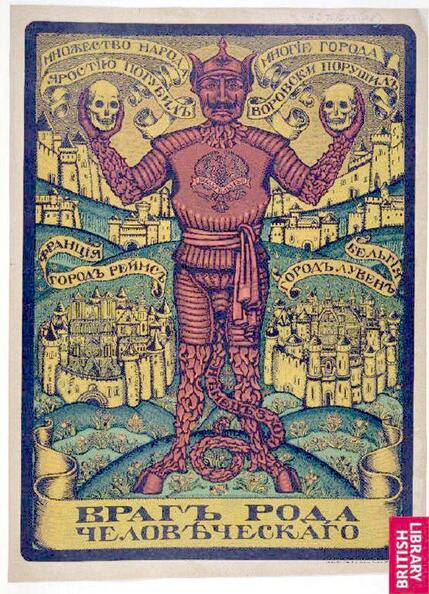

War hysteria was spread by vilifying publications and widespread rumors. The millions of semi-literate and non-literate Russians could not ascertain the facts and readily accepted the absurd propaganda. For example, it was claimed that a Volga German flour mill magnate was shipping a weekly trainload of flour from Saratov to Riga for Kaiser Wilhelm's forces. No one asked, and it was never explained, how an entire trainload of flour could travel hundreds of miles through Russia and across a war front manned by Russian troops every week.

War hysteria was spread by vilifying publications and widespread rumors. The millions of semi-literate and non-literate Russians could not ascertain the facts and readily accepted the absurd propaganda. For example, it was claimed that a Volga German flour mill magnate was shipping a weekly trainload of flour from Saratov to Riga for Kaiser Wilhelm's forces. No one asked, and it was never explained, how an entire trainload of flour could travel hundreds of miles through Russia and across a war front manned by Russian troops every week.

Even though there was no documented case of a German colonist being charged with treason or sabotage, the anti-German campaign continued. Most German-language newspapers were closed or suppressed. Approximately 190,000 to 200,000 ethnic Germans living in Russia were deported to Siberia from 1915 to 1916, including several pastors. The number of losses is unknown, but a mortality rate of one-third to one-half (63,000-100,000) is estimated.

In 1916, an order was issued to deport the entire Volga German population (around 650,000 at the time) to Siberia. The 1917 Socialist Revolution prevented the wholesale deportation from being carried out. About this turn of events, the author and poet Peter Sinner wrote:

In 1916, an order was issued to deport the entire Volga German population (around 650,000 at the time) to Siberia. The 1917 Socialist Revolution prevented the wholesale deportation from being carried out. About this turn of events, the author and poet Peter Sinner wrote:

When the storm had subsided, our German colonists saw themselves betrayed once more. The temporary government immediately halted the fierce expulsion law, but they did not rescind it. The general quartermaster of the temporary government renewed the prohibition of the German language. The war would be continued,

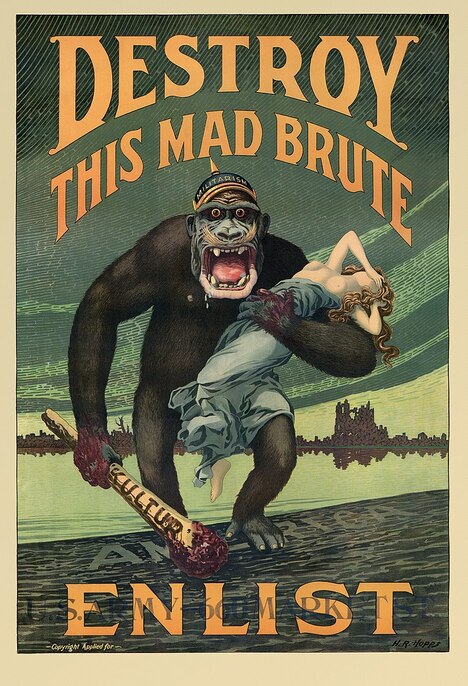

The situation was also growing dire for ethnic Germans living In the United States. Anti-German sentiment and propaganda reached extreme levels after America entered the war in April 1917. The German language was forbidden to be used in many places. German language newspapers were closed, and several editors were sent to internment camps. Germans were tarred and feathered in 13 states, including Oregon. German books were banned in libraries and burned in public ceremonies. Popular publications, such as Life Magazine, frequently featured German propaganda caricatures. At least one of these illustrations, titled "Der Oudtlaw" [sic], encouraged mob lynching of Germans suspected of being unpatriotic. Sadly, a German immigrant named Robert Paul Prager was hung by a group of vigilantes in 1918 outside of Collinsville, Illinois. The vigilantes were applauded in court for "doing their part." The jury deliberated for 10 minutes before acquitting those responsible for the murder despite the fact there was no evidence supporting the claims against Prager. Such was the anti-German hysteria of this period.

Given the strong anti-German mood across the country, the war years were an anxious time for the Volga Germans living in Portland. Although they valued their ethnic German heritage and language, they also considered themselves loyal Americans. Their ancestors migrated from the Germanic-speaking parts of western Europe in the mid-1760s. Since Germany did not become a unified country until 1871, the Volga Germans had no allegiance to this recently formed empire. Most Volga Germans living in Portland no longer knew where their family had come from in German-speaking Europe.

Regardless, most Americans did not differentiate between Germans who had immigrated directly from Germany and the Volga Germans who had only a distant connection to their ancestral homeland.

Anti-German pressure caused some families to anglicize the spelling of their surnames, for example from. Schmidt to Smith or Grün to Green. Name changes were often recommended to parents by public school officials. Children were forbidden to speak German in school and were disciplined if they did. In Portland, teaching the German language in schools was banned by the fall of 1918. Individuals and churches were put under surveillance. Government employees and self-appointed "patriots" frequently monitored church services from the sanctuary's back row, listening for "subversive" activities. Individuals were coerced to buy Liberty Bonds to demonstrate their loyalty.

The Volga Germans stayed within their community as much as possible during the war years. They wanted the outside world to understand and accept them as ethnic Germans who had lived in Russia and were now loyal citizens of the United States. One of their own, Jacob Volz, Jr., had been recently awarded the Medal of Honor based on his actions during the Moro Rebellion in the Philippines in 1911.

Regardless, most Americans did not differentiate between Germans who had immigrated directly from Germany and the Volga Germans who had only a distant connection to their ancestral homeland.

Anti-German pressure caused some families to anglicize the spelling of their surnames, for example from. Schmidt to Smith or Grün to Green. Name changes were often recommended to parents by public school officials. Children were forbidden to speak German in school and were disciplined if they did. In Portland, teaching the German language in schools was banned by the fall of 1918. Individuals and churches were put under surveillance. Government employees and self-appointed "patriots" frequently monitored church services from the sanctuary's back row, listening for "subversive" activities. Individuals were coerced to buy Liberty Bonds to demonstrate their loyalty.

The Volga Germans stayed within their community as much as possible during the war years. They wanted the outside world to understand and accept them as ethnic Germans who had lived in Russia and were now loyal citizens of the United States. One of their own, Jacob Volz, Jr., had been recently awarded the Medal of Honor based on his actions during the Moro Rebellion in the Philippines in 1911.

Newspaper columnist Karl Klooster wrote about the dilemma faced by Portland's Volga German community in a 1987 Round the Roses column:

World War I produced a strange paradox for the former Volga villagers. Anti-German sentiment ran deep in Portland but these folks were hybrids. Better, they undoubtedly reasoned, to be a "damned Rooshun" than a hated "Hun."

Hundreds of men living in Portland's Volga German community registered for the military draft. Young men like Charlie Bauer, Jacob Kanzler and Adam Lewis Jorg, proudly served in the U.S. military during World War I. It is ironic that despite anti-German sentiment in Russia and the USA, Volga German men in both countries fought against Imperial Germany and her allies.

Charlie Bauer is seated in the center of the front row of this group of U.S. soldiers who served in World War I. Charlie was the son of Heinrich and Katherine Bauer from Norka and was born in Oregon in 1894. This photograph was taken in Trier, Germany in 1917 and was provided courtesy of Kris Dillman.

World War I and the Russian Revolution ended the migration of Volga Germans to the United States. Without a continual influx of immigrants from Russia, the forces of assimilation grew stronger in the Portland community. As anti-German hysteria receded, the fear of Soviet communism was on the rise. This created another dilemma for the Volga Germans, who now had to reject their Russian identity for fear of being labeled as Bolsheviks or Communists.

For the Volga Germans living in Russia, the war's end was a welcome relief. However, the devastating impacts of the Russian Revolution, Civil War, and famine were close at hand. These tragic events would sever the ties between family and friends living in Russia and Portland for decades.

For the Volga Germans living in Russia, the war's end was a welcome relief. However, the devastating impacts of the Russian Revolution, Civil War, and famine were close at hand. These tragic events would sever the ties between family and friends living in Russia and Portland for decades.

Sources

Hagwood, John A. The Tragedy of German America: The Germans in the United States of America During the Nineteenth Century - and After. New York: Putnam, 1940.

Kirschbaum, Erik. Burning Beethoven: the Eradication of German Culture in the United States during World War I. Berlinica, 2015. Pages 103 and 141. Print.

Klooster, Karl. "Round the Roses Column: Notes and Anecdotes", This Week Magazine (a supplement to The Oregonian), October 28, 1987.

Koch, Fred C. The Volga Germans: In Russia and the Americas, from 1763 to the Present. University Park: Pennsylvania State UP, 1977. 221-240. Print.

Little, Becky. When German Immigrants Were America’s Undesirables. History.com, 18 May 2018.

Long, James. From Privileged to Dispossessed. Lincoln, Nebraska: U of Nebraska, 1988. 14-15. Print.

Sallet, Richard. Russian-German Settlements in the United States. Fargo: North Dakota Institute for Regional Studies, 1974. Print.

Schwabauer, Wanda J. "The Portland Community of Germans from Russia." Diss. Portland State U, 1974. Print.

Sinner, Peter. Germans in the Land of the Volga. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1989. Print.

Sinner, Samuel D. "The German-Russian Genocide: Remembrance in the 21st Century." Presentation to the Oregon Chapter, American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, August 28, 2005, Portland, Oregon

Kirschbaum, Erik. Burning Beethoven: the Eradication of German Culture in the United States during World War I. Berlinica, 2015. Pages 103 and 141. Print.

Klooster, Karl. "Round the Roses Column: Notes and Anecdotes", This Week Magazine (a supplement to The Oregonian), October 28, 1987.

Koch, Fred C. The Volga Germans: In Russia and the Americas, from 1763 to the Present. University Park: Pennsylvania State UP, 1977. 221-240. Print.

Little, Becky. When German Immigrants Were America’s Undesirables. History.com, 18 May 2018.

Long, James. From Privileged to Dispossessed. Lincoln, Nebraska: U of Nebraska, 1988. 14-15. Print.

Sallet, Richard. Russian-German Settlements in the United States. Fargo: North Dakota Institute for Regional Studies, 1974. Print.

Schwabauer, Wanda J. "The Portland Community of Germans from Russia." Diss. Portland State U, 1974. Print.

Sinner, Peter. Germans in the Land of the Volga. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1989. Print.

Sinner, Samuel D. "The German-Russian Genocide: Remembrance in the 21st Century." Presentation to the Oregon Chapter, American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, August 28, 2005, Portland, Oregon

Last updated October 21. 2023