Garbage Haulers

Collecting garbage in the City of Portland was often a family affair and a Volga German one at that. Although some Italians and Germans operated garbage routes, nearly all of the garbage collection businesses in Portland were operated by families with Volga German ancestry.

The garbage business was unregulated in the late 1800s and early 1900s, and it gave the Volga German immigrants, many of whom could not speak English, an opportunity to begin a business with a modest investment. The Volga Germans were accustomed to hard work and long hours and fared well in the competitive garbage-hauling business.

The garbage business was unregulated in the late 1800s and early 1900s, and it gave the Volga German immigrants, many of whom could not speak English, an opportunity to begin a business with a modest investment. The Volga Germans were accustomed to hard work and long hours and fared well in the competitive garbage-hauling business.

In the early years of settlement, the garbage business was an unregulated free market. Each owner went door to door to persuade the homeowner or business owner to use their service. As a result, numerous companies served the same block. This kept pricing low and competitive tensions between haulers high. The men worked six days a week from dawn to dark.

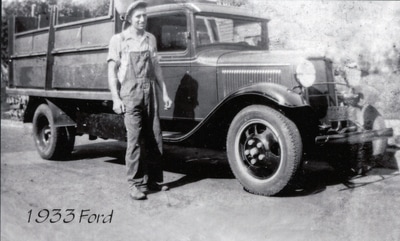

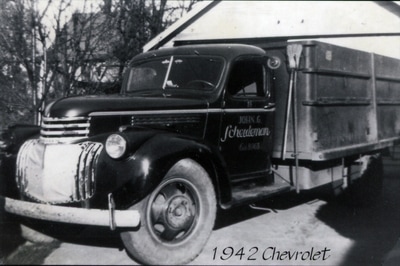

Collection equipment in the early days included horses, wooden wagons, and a strong back. The horses were often grazed in the open fields, including what is now Irving Park, and the wagons were stored in a large garage adjacent to the hauler's home.

Some early Volga German pioneers who settled in Portland, such as John Leel, are listed in the City Directories as "scavengers" as early as 1894. Scavenger was the term used in the 1800s and early 1900s to describe people who collected, hauled away, and resold discarded materials.

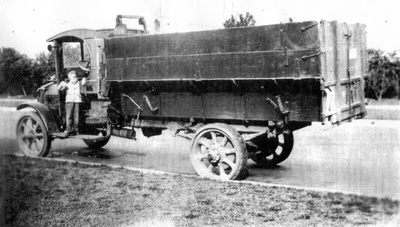

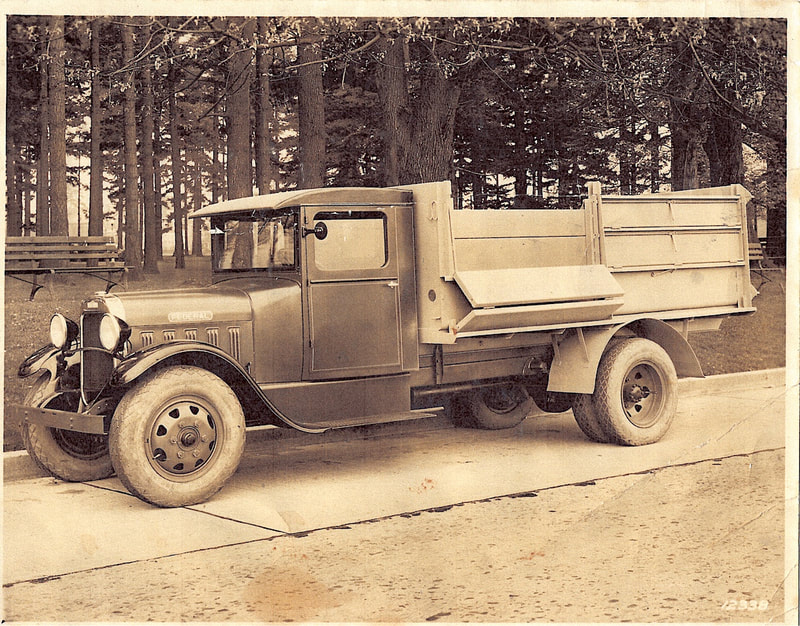

Johnny Walker (changed from Wacker), Sr. started hauling trash in a horse-drawn wagon in the early 1900's. He was the first trash hauler in Portland to use a motorized truck, a 1917 Garford. Rather than grow and take on employees, Johnny would sell what work he and his family could not do themselves. One of his first sales developed into a large corporation named MDC Disposal, which later became USA Waste and is now Waste Management Inc.

One of the earliest settlers in Portland, Adam Schwindt, is listed as a scavenger in the 1901 Portland City Directory. Henry Aschenbrenner was in the business by 1910.

In 1907, Glanz Bros. Co. and the John Deines Company were started with a one-horse and wagon. The Glanz Bros. were considered one of the most progressive operators pioneering the use of elevators on trucks and the drop box system.

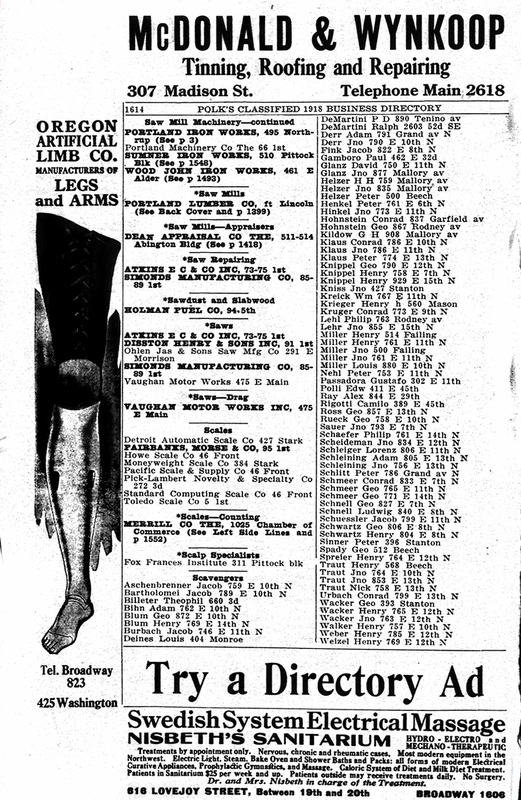

The list of "Scavengers" published in the 1918 Portland City Directory shows that nearly all of the garbage haulers at that time were Volga Germans. One of those listed, George Schmeer, had the distinction of being arrested by the Mayor of Portland in 1919, but he ended up having the last laugh.

Acting as “scavengers,” the garbagemen found items thrown away by more affluent folks that could be reused. They called it “skibby”.

Collection equipment in the early days included horses, wooden wagons, and a strong back. The horses were often grazed in the open fields, including what is now Irving Park, and the wagons were stored in a large garage adjacent to the hauler's home.

Some early Volga German pioneers who settled in Portland, such as John Leel, are listed in the City Directories as "scavengers" as early as 1894. Scavenger was the term used in the 1800s and early 1900s to describe people who collected, hauled away, and resold discarded materials.

Johnny Walker (changed from Wacker), Sr. started hauling trash in a horse-drawn wagon in the early 1900's. He was the first trash hauler in Portland to use a motorized truck, a 1917 Garford. Rather than grow and take on employees, Johnny would sell what work he and his family could not do themselves. One of his first sales developed into a large corporation named MDC Disposal, which later became USA Waste and is now Waste Management Inc.

One of the earliest settlers in Portland, Adam Schwindt, is listed as a scavenger in the 1901 Portland City Directory. Henry Aschenbrenner was in the business by 1910.

In 1907, Glanz Bros. Co. and the John Deines Company were started with a one-horse and wagon. The Glanz Bros. were considered one of the most progressive operators pioneering the use of elevators on trucks and the drop box system.

The list of "Scavengers" published in the 1918 Portland City Directory shows that nearly all of the garbage haulers at that time were Volga Germans. One of those listed, George Schmeer, had the distinction of being arrested by the Mayor of Portland in 1919, but he ended up having the last laugh.

Acting as “scavengers,” the garbagemen found items thrown away by more affluent folks that could be reused. They called it “skibby”.

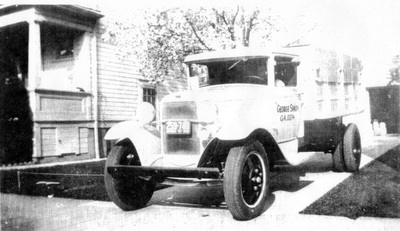

Around 1921, the first trucks with spoked wheels and solid rubber tires were purchased to make the work more efficient. Philip Leichner was the first garbageman in Portland to own a truck with a steel box. Leichner went on to establish the Vancouver Sanitary Service.

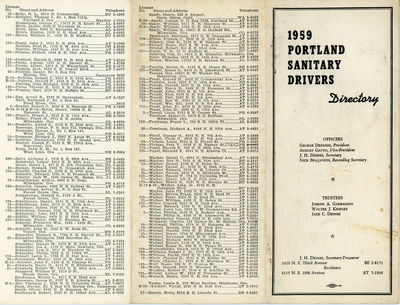

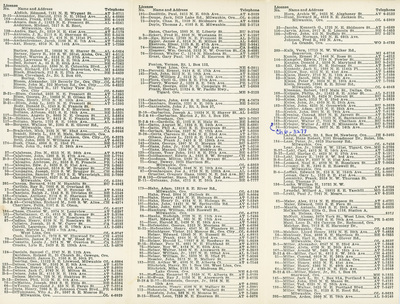

The garbage haulers took great pride in forming their union, Local 220, in late 1920. The newly formed local, representing about 75 drivers, was part of the Joint Council of Teamsters No. 37. The Teamsters Local No. 162 website states:

"The camaraderie and brotherhood among these early sanitary drivers is legendary - they were a rough bunch."

In those early days after the garbage truck drivers formed an association, they held their first meetings in the basement of various member's houses and wrote their minutes in German. One of their first achievements was to buy chairs, which were shifted from basement to basement each year. As the industry grew with the addition of new members, the meeting locations changed and, for many years, were held at the old Steuben Hall on Williams Avenue and Ivy Street.

In later years, many of the Volga German "G-Men" gathered regularly at Henry "Dixie" Wunsch's home to socialize, drink and share stories. Summer picnics were held in local area parks and were always fun-filled events.

While the garbage haulers had their rough side, they also had soft hearts. Most could be found in church on Sunday mornings, and they generously supported the needs of their congregations. They were also strong supporters of the Volga Relief Society in the early 1920s, providing aid to family and friends suffering from a severe famine in Russia.

Many of Portland's finest homes and parks sit atop landfills "scientifically" designed by the City of Portland's Bureau of Refuse Disposal. In their own way, the Volga German garbagemen did their part to aid in the sculpting and development of the city.

The earliest dump sites were located outside the city limits. The "scavengers" went on strike in 1884, protesting the long hauling distances. A dumpsite was established near Guild's Lake, located on the city's northern edge at that time. No improved roads led to the site, making it difficult for garbage haulers to access, especially during Portland’s rainy season. In 1888, the city hired a contractor to build a garbage incinerator (also called a crematory) on the western shore of Guild’s Lake near the existing garbage dump. At this time, the city began collecting a licensing fee to use the dump site. The incinerator was completed in 1889 but was soon deemed a failure as unburned garbage piled up. Several other incinerators were constructed in the late 1800s, but they all suffered from mechanical problems and were shut down. In December 1889, The Oregonian published an article that asked a recurring question in Portland, "What shall we do with our garbage?"

Depleted gravel pits located at NE 33rd and Fremont (1923), between NE 37th and 38th and Klickitat and Siskiyou Streets, and south of the Rose City Golf Course at NE 65th and Tillamook were put to use as dumpsites. Next came the Penn Street gulch, which provided roadway access to the new Swan Island Airport. A small sand pit in St. Johns was also filled with garbage, as was a small gulch at Alberta and Greeley. Another gravel pit was filled at Alberta and 39th, followed by a gulch on Interstate Avenue in an area that is now Overlook Park. The Oregon Journal claimed that garbage hauler Ludwig Deines did as much as any man to make Overlook Park a reality. A large landfill at East 90th was filled and closed in 1946.

In later years, many of the Volga German "G-Men" gathered regularly at Henry "Dixie" Wunsch's home to socialize, drink and share stories. Summer picnics were held in local area parks and were always fun-filled events.

While the garbage haulers had their rough side, they also had soft hearts. Most could be found in church on Sunday mornings, and they generously supported the needs of their congregations. They were also strong supporters of the Volga Relief Society in the early 1920s, providing aid to family and friends suffering from a severe famine in Russia.

Many of Portland's finest homes and parks sit atop landfills "scientifically" designed by the City of Portland's Bureau of Refuse Disposal. In their own way, the Volga German garbagemen did their part to aid in the sculpting and development of the city.

The earliest dump sites were located outside the city limits. The "scavengers" went on strike in 1884, protesting the long hauling distances. A dumpsite was established near Guild's Lake, located on the city's northern edge at that time. No improved roads led to the site, making it difficult for garbage haulers to access, especially during Portland’s rainy season. In 1888, the city hired a contractor to build a garbage incinerator (also called a crematory) on the western shore of Guild’s Lake near the existing garbage dump. At this time, the city began collecting a licensing fee to use the dump site. The incinerator was completed in 1889 but was soon deemed a failure as unburned garbage piled up. Several other incinerators were constructed in the late 1800s, but they all suffered from mechanical problems and were shut down. In December 1889, The Oregonian published an article that asked a recurring question in Portland, "What shall we do with our garbage?"

Depleted gravel pits located at NE 33rd and Fremont (1923), between NE 37th and 38th and Klickitat and Siskiyou Streets, and south of the Rose City Golf Course at NE 65th and Tillamook were put to use as dumpsites. Next came the Penn Street gulch, which provided roadway access to the new Swan Island Airport. A small sand pit in St. Johns was also filled with garbage, as was a small gulch at Alberta and Greeley. Another gravel pit was filled at Alberta and 39th, followed by a gulch on Interstate Avenue in an area that is now Overlook Park. The Oregon Journal claimed that garbage hauler Ludwig Deines did as much as any man to make Overlook Park a reality. A large landfill at East 90th was filled and closed in 1946.

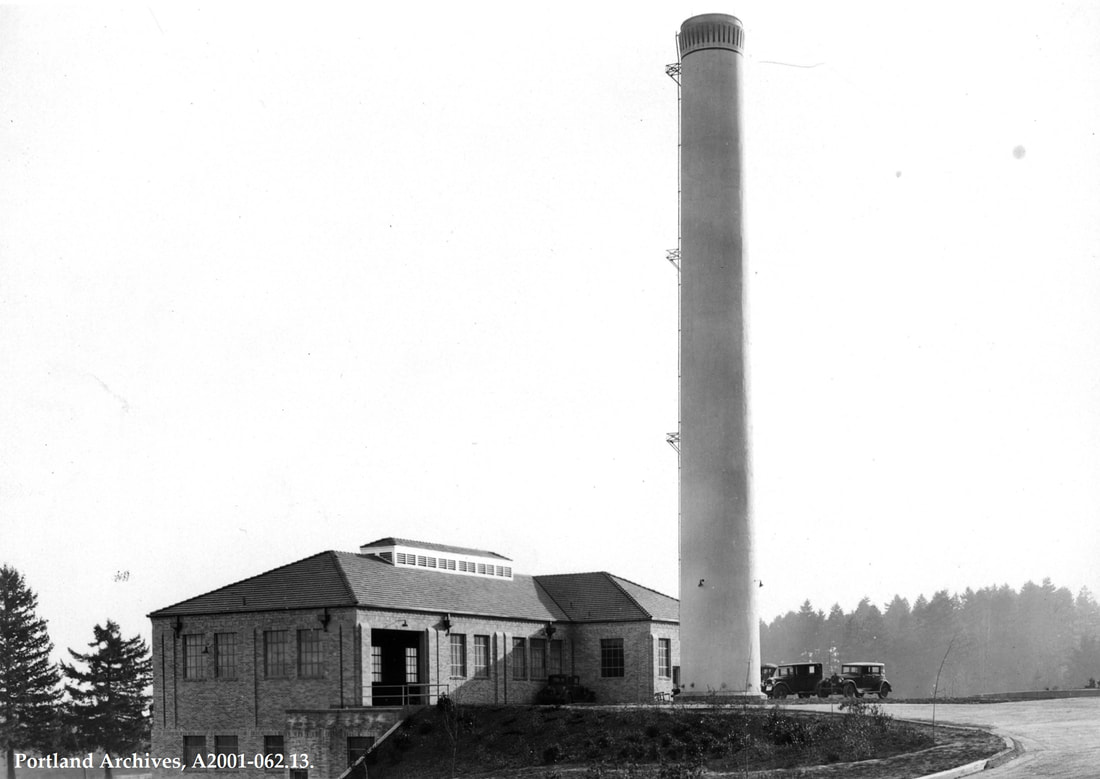

In 1932, the city returned to incinerator technology to solve Portland's garbage disposal problems. A large incinerator was built in St. Johns (at 9360 Swift Blvd. between the Columbia Slough and Smith and Bybee Lakes) adjacent to a 296-acre dumping ground. The city required the haulers to wash their trucks after dropping each load. After nearly 60 years of use, the St. Johns landfill was closed by Metro in 1990. Chimney Park now occupies the site of the incinerator, acquiring its name from the incinerator's chimney, which has since been removed for safety reasons.

The City of Portland built this incinerator facility on N. Columbia Blvd. in 1932. Air quality standards forced its closure in 1970 and the building became the Archives and Records Center for the City of Portland in the 1980s. The Archives and Records Center was later moved to a climate-controlled facility on the Portland State University campus but this building still remains in North Portland. This site is now called Chimney Park although ironically, the chimney was removed in 1990. This view looks west with N. Columbia Blvd. on the right. Vintage Portland website May 30, 2012. Photo source: City of Portland Archives.

Some of the garbagemen were known to stop for a drink at the Blow Fly Inn after the end of a long work day. The Blow Fly was located on Swift Avenue (now Columbia Blvd.) between the St. Johns Landfill and the City of Portland incinerator.

My name is Nicholas Harry Hohnstein. My father, Nicholas Hohnstein was in the garbage business until about 1945. We lived at 6522 N. Kerby Avenue.

I remember going to John Deines' house when I was very young. My father always referred to his truck as the "Sugar Wagon" and the men would always stop at the Blow Fly Inn which was located near the city dump for a beer at the end of the day.

In winter, the garbage haulers frequently came to the city's rescue by helping dispose of tons of accumulated snow that threatened to bring Portland to a halt.

The garbage business was featured on the front page of the Oregonian in October 1938 when Ed Weber innocently hauled away a valuable piece of radium.

In July 1941, members of the sanitary truck drivers union volunteered (at no cost to the federal government) to collect all the garbage left behind by a 6,500 troop military encampment at the Swan Island Airport.

During the Vanport Flood in 1948, the garbage haulers were among the first responders to help people in need. Upon receiving notification about the rising waters in Vanport, many men drove their trucks from Albina to the flood zone. The men opened the back and side gates of the specially made boxes of their trucks and hauled everything from people to household goods out to higher ground. According to Harold Kammerzell, the St. John's landfill was closed during the flood, and a temporary site was opened around NE 135th and Halsey.

In July 1941, members of the sanitary truck drivers union volunteered (at no cost to the federal government) to collect all the garbage left behind by a 6,500 troop military encampment at the Swan Island Airport.

During the Vanport Flood in 1948, the garbage haulers were among the first responders to help people in need. Upon receiving notification about the rising waters in Vanport, many men drove their trucks from Albina to the flood zone. The men opened the back and side gates of the specially made boxes of their trucks and hauled everything from people to household goods out to higher ground. According to Harold Kammerzell, the St. John's landfill was closed during the flood, and a temporary site was opened around NE 135th and Halsey.

Many of the family-founded businesses continued to expand as Portland grew. Sons were brought into existing businesses or started their own companies. As of the mid-1950s, around 250 companies were operating in Portland. While most haulers operated in the greater Portland metropolitan area, including the downtown commercial districts, men like Bud Walker, Henry Schaefer, and George Lehl set up businesses in towns on the Oregon coast and as far south as Eugene-Springfield. Ezra and Fred Koch established a collection business in McMinnville. Art Rossman began operations in Lake Oswego, and George Rossman owned a landfill near Oregon City. Art and Don Schauermann established themselves in Forest Grove. Ben Koch and Al Usinger established collection routes in The Dalles. Ed Brandt set up collection services in Monmouth. The Maiers went to Hillsboro, and Bill Schmitt moved to Salem. Others set up successful businesses in Washington, Idaho, and California. Philip Hohnstein left Portland for southern California; Henry Koch, Peter Koch, and Ray Schauermann started businesses in Kennewick; Walter Pauley in Pullman and Jim Hinkle in Ellensburg. The Leichners expanded into Vancouver, and John Urbach was successful in Idaho Falls. Arne Markstaller established a business in Moscow, Idaho, and John Miller established routes in Prosser, Idaho.

The unregulated nature of the garbage hauling business created closer scrutiny beginning in the late 1940s with concerns about it being a "closed corporation of employers and the union." In the mid-1950s, the City Club of Portland formed a committee to study Portland's garbage collection and disposal system. The committee's 63-page report raised concerns about the monopolistic nature of the garbage haulers in Portland. However, the report contained only three recommendations, one of which was to preserve the existing system.

More controversy struck the industry in the spring of 1963 when the Teamsters announced a 25-cent per can increase (on a base of $1.50 per can per week) for most residential and commercial customers. The complaints were directed to City Hall, although the City Council did not formally approve rates then. Some independent (non-union) operators chose not to increase rates and allegedly met with hostility from the union operators. A truck owned by the independent Lehl Sanitary Co. was burned, and the owner claimed he was being harassed by the union. John H. Deines, secretary of Local 220, made no comment about the truck burning but did say, "We've got 400 members, and who knows how each one of them feels about it." At this time, about 30 to 40 companies were operating 228 licensed trucks in Portland. Despite the controversy, City Commissioner William A. Bowes called Portland a "paradise" compared to other cities in garbage collection services and said the homeowners pay one of the lowest rates in the country for comparable cities. Bowes remarked, "Here, you not only don't have to separate it, but they even come to your backyard and pick it up."

In 1987, Portland began requiring all garbage and recycling companies to offer recycling services to their customers. Consolidation in the industry began, and by 1989, 112 companies were operating in Portland.

In 1992, Portland adopted a franchise system for the residential collection sector. The franchise system was also proposed for the commercial sector, but the business community expressed a strong desire to retain a free market system. The Residential Franchise Agreement, still in place today, assigned Portland garbage and recycling companies serving residential customers to specific areas of the city. When this system first started, there were 69 residential garbage and recycling companies. By 2013, there were only 18 franchised residential collection companies in Portland, many still owned by Volga German families.

No matter how bad business gets for others, the garbage haulers have a standard joke. For them, "business is always picking up." That's fortunate for all of us.

The unregulated nature of the garbage hauling business created closer scrutiny beginning in the late 1940s with concerns about it being a "closed corporation of employers and the union." In the mid-1950s, the City Club of Portland formed a committee to study Portland's garbage collection and disposal system. The committee's 63-page report raised concerns about the monopolistic nature of the garbage haulers in Portland. However, the report contained only three recommendations, one of which was to preserve the existing system.

More controversy struck the industry in the spring of 1963 when the Teamsters announced a 25-cent per can increase (on a base of $1.50 per can per week) for most residential and commercial customers. The complaints were directed to City Hall, although the City Council did not formally approve rates then. Some independent (non-union) operators chose not to increase rates and allegedly met with hostility from the union operators. A truck owned by the independent Lehl Sanitary Co. was burned, and the owner claimed he was being harassed by the union. John H. Deines, secretary of Local 220, made no comment about the truck burning but did say, "We've got 400 members, and who knows how each one of them feels about it." At this time, about 30 to 40 companies were operating 228 licensed trucks in Portland. Despite the controversy, City Commissioner William A. Bowes called Portland a "paradise" compared to other cities in garbage collection services and said the homeowners pay one of the lowest rates in the country for comparable cities. Bowes remarked, "Here, you not only don't have to separate it, but they even come to your backyard and pick it up."

In 1987, Portland began requiring all garbage and recycling companies to offer recycling services to their customers. Consolidation in the industry began, and by 1989, 112 companies were operating in Portland.

In 1992, Portland adopted a franchise system for the residential collection sector. The franchise system was also proposed for the commercial sector, but the business community expressed a strong desire to retain a free market system. The Residential Franchise Agreement, still in place today, assigned Portland garbage and recycling companies serving residential customers to specific areas of the city. When this system first started, there were 69 residential garbage and recycling companies. By 2013, there were only 18 franchised residential collection companies in Portland, many still owned by Volga German families.

No matter how bad business gets for others, the garbage haulers have a standard joke. For them, "business is always picking up." That's fortunate for all of us.

Listed below are current (updated January 2017) garbage hauling companies in the Portland area that were established by Volga German families:

Alberta Sanitary Service

Gresham Sanitary Service

Mel Deines Sanitary Service

Dan Walker Disposal

Deines Brothers Sanitary Service (now Hoodview Disposal & Recycling)

John P. Lehl (now Waste Management of Oregon)

Oak Grove Disposal (now Waste Management of Oregon)

P. Deines Sanitary Service

Gaylen Kiltow Sanitary Service

Rossman Sanitary Service (now Republic Services)

Borgens Disposal

Lehl Disposal

Miller's Sanitary

Mohr Refuse

Montavilla Sanitary Service

John G. Scheideman

Troudt Brothers Sanitary

Wacker Sanitary

Walker Garbage Service

Weber Disposal

Weitzel & Son Refuse

Fred Wunsch Sanitary Service

Victor Yuckert

Gresham Sanitary Service

Mel Deines Sanitary Service

Dan Walker Disposal

Deines Brothers Sanitary Service (now Hoodview Disposal & Recycling)

John P. Lehl (now Waste Management of Oregon)

Oak Grove Disposal (now Waste Management of Oregon)

P. Deines Sanitary Service

Gaylen Kiltow Sanitary Service

Rossman Sanitary Service (now Republic Services)

Borgens Disposal

Lehl Disposal

Miller's Sanitary

Mohr Refuse

Montavilla Sanitary Service

John G. Scheideman

Troudt Brothers Sanitary

Wacker Sanitary

Walker Garbage Service

Weber Disposal

Weitzel & Son Refuse

Fred Wunsch Sanitary Service

Victor Yuckert

Photo Gallery

Sources

"U.S. Camp Garbage Removal Donated." The Oregonian [Portland} 14 July 1941: 9. Print.

Hoover, Helen. "Where Does Your Garbage Go?" The Sunday Oregonian [Portland] 26 Jan. 1947: 4. Print.

"Park Story Began With Garbage Man." Oregon Journal [Portland] 31 Jan. 1977: 13. Print.

Tripp, Julie. "Cleaning Up Portland." The Oregonian [Portland] 26 Dec. 2005: n. pag. Print.

"Portland of Years Past - 50 Years Ago: 1949." The Oregonian [Portland] 17 Jun. 1999. Print.

"Garbage, Garbage, Garbage... System Handles Tons Daily." The Sunday Oregonian [Portland] 13 Jan. 1963. 47. Print.

"Private Enterprise Stirs Fuss Among Garbage Collectors." The Sunday Oregonian [Portland] 5 May 1963; 14 Print.

Hunter, Bob. "George Frank: Two Companies, Many Friends." Tigard Times [Tigard, Oregon] 25 Aug. 1981: 5A. Print.

Garbage Collection and Disposal in Portland. Publication. Portland, Oregon: City Club of Portland, 1955. Print.

Kammerzell, Harold. Oral interviews.

Kirkpatrick, Allison. "As Great a Nuisance as Garbage Itself". Oregon Historical Society Quarterly, Winter 2022.

Krieger, Marie. Oral interviews.

Schleining, Jerry. Oral interviews.

Koch, Norman. Emails dated December 8, 2015 and January 21, 2016.

Wunsch, Dixie. Oral interviews.

History of Portland's Garbage and Recycling System - City of Portland website (May 2015)

History of City Sanitary Service - City Sanitary website (May 2015)

Mill, Pennee. Email dated 12 Jan 2018 regarding Philip Leichner and the Vancouver Sanitary Service.

Hoover, Helen. "Where Does Your Garbage Go?" The Sunday Oregonian [Portland] 26 Jan. 1947: 4. Print.

"Park Story Began With Garbage Man." Oregon Journal [Portland] 31 Jan. 1977: 13. Print.

Tripp, Julie. "Cleaning Up Portland." The Oregonian [Portland] 26 Dec. 2005: n. pag. Print.

"Portland of Years Past - 50 Years Ago: 1949." The Oregonian [Portland] 17 Jun. 1999. Print.

"Garbage, Garbage, Garbage... System Handles Tons Daily." The Sunday Oregonian [Portland] 13 Jan. 1963. 47. Print.

"Private Enterprise Stirs Fuss Among Garbage Collectors." The Sunday Oregonian [Portland] 5 May 1963; 14 Print.

Hunter, Bob. "George Frank: Two Companies, Many Friends." Tigard Times [Tigard, Oregon] 25 Aug. 1981: 5A. Print.

Garbage Collection and Disposal in Portland. Publication. Portland, Oregon: City Club of Portland, 1955. Print.

Kammerzell, Harold. Oral interviews.

Kirkpatrick, Allison. "As Great a Nuisance as Garbage Itself". Oregon Historical Society Quarterly, Winter 2022.

Krieger, Marie. Oral interviews.

Schleining, Jerry. Oral interviews.

Koch, Norman. Emails dated December 8, 2015 and January 21, 2016.

Wunsch, Dixie. Oral interviews.

History of Portland's Garbage and Recycling System - City of Portland website (May 2015)

History of City Sanitary Service - City Sanitary website (May 2015)

Mill, Pennee. Email dated 12 Jan 2018 regarding Philip Leichner and the Vancouver Sanitary Service.

Last updated October 30, 2023