History > History of Albina

A Short History of Albina

The area's earliest inhabitants that came to be known as Albina were the native tribes. The Albina area falls within the tribal grounds of the Clackamas people, whose lands extended from the Willamette River east to the Cascade mountains.

Many early European settlers reached Albina via the Barlow Road, which ended on the east side of the Willamette River, south of Albina.

Many early European settlers reached Albina via the Barlow Road, which ended on the east side of the Willamette River, south of Albina.

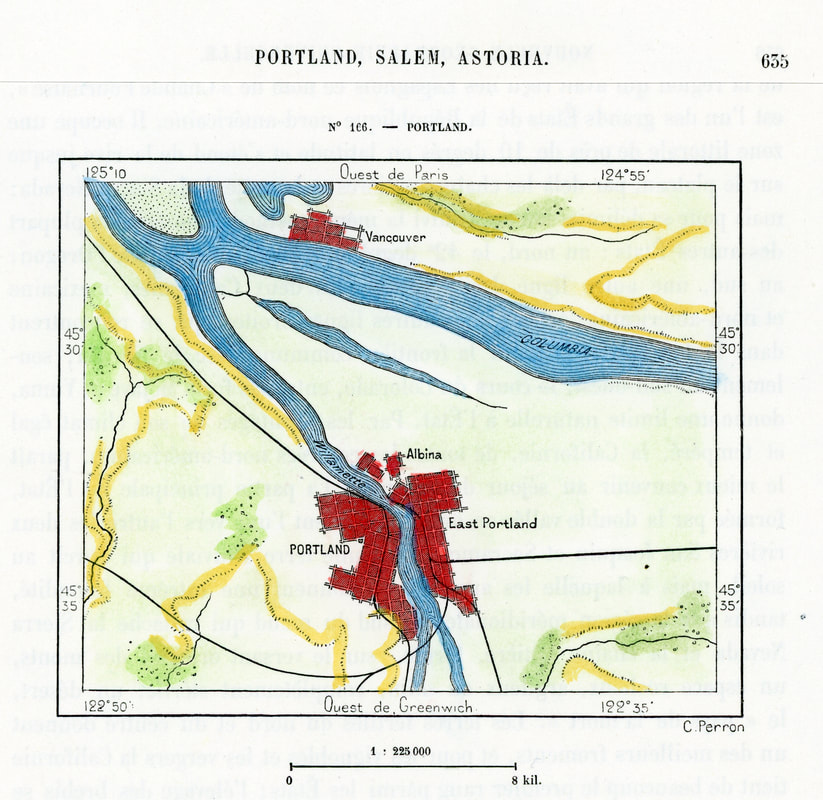

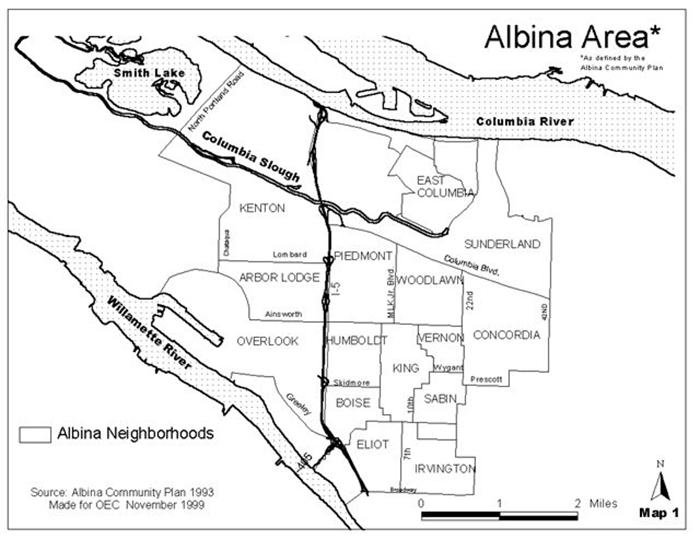

The original dimensions of Albina were modest, encompassing and area from Tillamook Street (then Grant Street) on the south, north to Russell and Morris Streets, and from the Willamette River to Margaretta Avenue. (This road later became Union Avenue and is currently Martin Luther King Boulevard).

The history of Albina reflects the tremendous economic opportunities available to and exploited by early settlers and businessmen in Portland. Many of Portland's pioneers acquired property at little cost through the Donation Land Act of 1850. The act granted free land to settlers who would agree to live upon and cultivate their claims for four consecutive years.

Albina was located on a donation land claim owned by J.L. Loring and Joseph Delay. The land was later sold to attorney William Winter Page. The original town site was named after the wife and daughter of William Page, who were both named Albina (pronounced Al-Bean-ah, according to the family).

In 1872, Page sold the land to Edwin Russell, manager of the Portland branch of the Bank of British Columbia, and George H. Williams, former senator, U.S. Attorney General, and future mayor of Portland. Today, Northeast Russell Street and Williams Avenue carry their names. Margaretta Avenue was the main north-south street that formed the original eastern boundary of Albina. It was named after Margaretta Russell, the wife of Edwin Russell. This street was the extension of Fourth Street in East Portland, and it again became Fourth Street (or Avenue) north of Albina. In 1892, Union Avenue was renamed to standardize the name and commemorate the consolidation of Albina, East Portland, and Portland in 1891. In 1989, the street was renamed Martin Luther King Boulevard to honor Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

A plat for the new town was filed in 1873 by Russell and Williams. At the time, the area was a virtual wilderness with no streets and heavily forested land to the east and north.

The history of Albina reflects the tremendous economic opportunities available to and exploited by early settlers and businessmen in Portland. Many of Portland's pioneers acquired property at little cost through the Donation Land Act of 1850. The act granted free land to settlers who would agree to live upon and cultivate their claims for four consecutive years.

Albina was located on a donation land claim owned by J.L. Loring and Joseph Delay. The land was later sold to attorney William Winter Page. The original town site was named after the wife and daughter of William Page, who were both named Albina (pronounced Al-Bean-ah, according to the family).

In 1872, Page sold the land to Edwin Russell, manager of the Portland branch of the Bank of British Columbia, and George H. Williams, former senator, U.S. Attorney General, and future mayor of Portland. Today, Northeast Russell Street and Williams Avenue carry their names. Margaretta Avenue was the main north-south street that formed the original eastern boundary of Albina. It was named after Margaretta Russell, the wife of Edwin Russell. This street was the extension of Fourth Street in East Portland, and it again became Fourth Street (or Avenue) north of Albina. In 1892, Union Avenue was renamed to standardize the name and commemorate the consolidation of Albina, East Portland, and Portland in 1891. In 1989, the street was renamed Martin Luther King Boulevard to honor Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

A plat for the new town was filed in 1873 by Russell and Williams. At the time, the area was a virtual wilderness with no streets and heavily forested land to the east and north.

The townsite was initially developed along the railroad tracks in lower Albina and to the east along Russell Street. The first subdivision was also platted in 1873, creating residential lots that extended east of the current Martin Luther King (MLK) Blvd. and north past NE Morris Street.

Settlement of the area began in 1874. An advertisement published in The Oregonian on July 22, 1876, touted the following opportunities in Albina:

"Homestead Lots for sale in this rapidly growing town, above high water, and with a fine view of the City of Portland, from One Hundred Dollar upwards, and on easy terms of payment. The location is unsurpassed for health and enjoys a cool breeze from the North in the hottest weather. A new Postoffice with daily mail has been established. Special inducements given to manufactories of all kinds along the river front. The Ferry Boat leaves from foot of H street every few minutes. For particulars apply at the office of Oregon Iron Works, on the ground, or to ATKINSON & WAKEFIELD. Corner Front and Stark Streets."

In 1880, just one year before the arrival of the first Volga Germans, only 143 people were living in Albina. At this time, over 50 percent of those living in Portland were foreign-born or had at least one immigrant parent. By 1890, that percentage would increase to 60 percent.

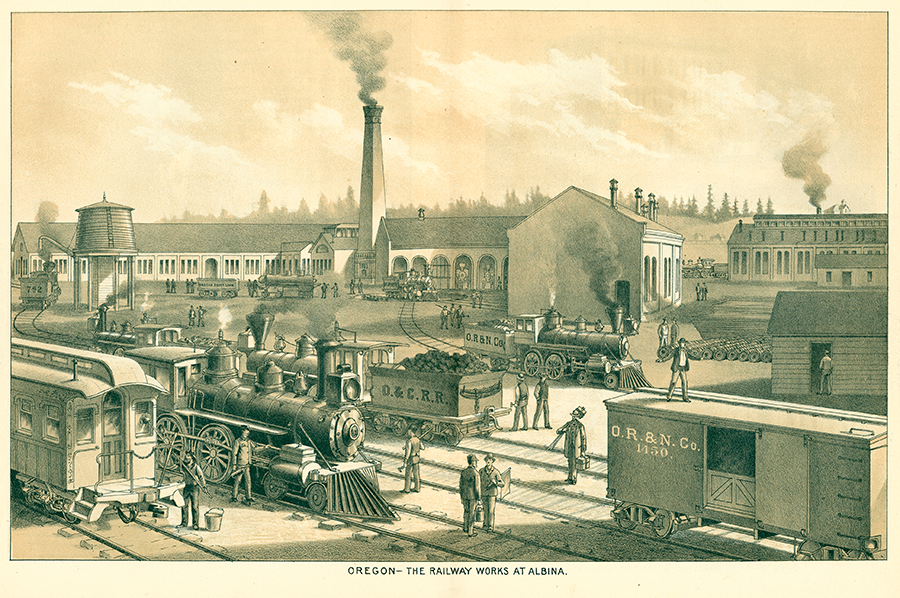

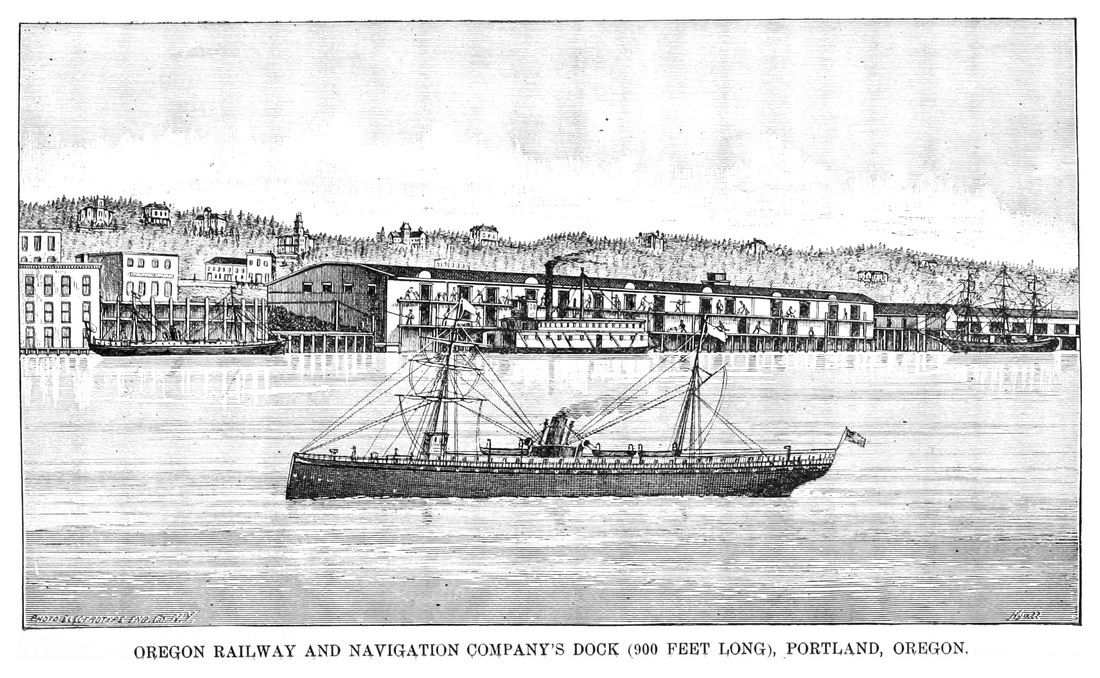

In March 1882, construction of the Oregon Railroad and Navigation Company (OR&NC) "Great Depot" began in the marshland below Albina. The depot included car and machine shops and a vast rail yard. The development caused Albina's population and property values to soar. Five railroads planned to locate their terminal at Albina. It was reported in The Oregonian that no fewer than 300 men would be employed in the car and machine shops, and nearly 4,000 would be employed at the freight and passenger depots, the roundhouse, shipping docks, coal terminal, grain terminals, and dry dock. In addition, it was expected that the expansion of the railroad operations would stimulate related businesses such as hotels, hardware stores, grocery stores, etc.

Construction of the transcontinental railroad to Portland was celebrated in September 1883, and the first trains running from Portland to Walla Walla began operating in November. Anticipating completion of the line, Henry Villard ordered that a small passenger station be built during the summer of 1883 at a cost of no more than $5,000. The station, located in East Portland at the foot of Cedar Street, was completed by September.

The direct railway connection to the Midwest and Eastern United States spurred additional growth in Albina and facilitated increased migration of Volga Germans to Albina.

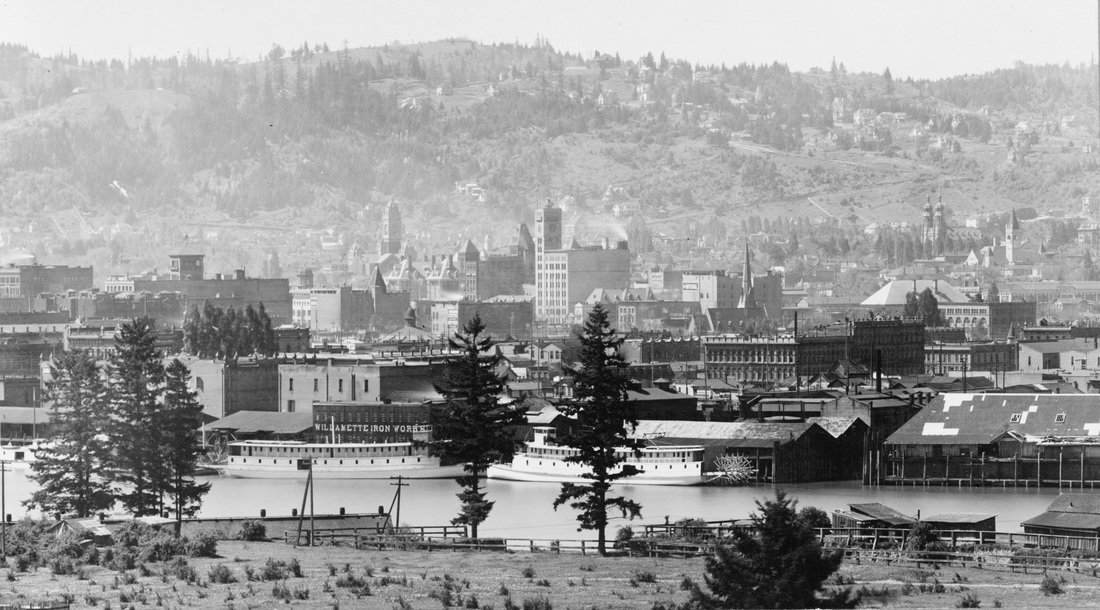

The 1884 Sanborn Insurance Map of Albina shows that the primary businesses included the seven-story Portland Flouring Mills (incorporated by William S. Ladd), Albina Sawing and Planing Mills, Oregon Iron Works, the Montgomery grain dock, and the OR&NC rail operations.

By the late 1880s, Albina became the fastest-growing city in Oregon and a company town, the company being the OR&NC. The OR&NC was founded by Henry Villard. Villard was also President of the Northern Pacific Railroad and a real estate investor in Albina. He had many connections with the influential businessmen in Portland. The OR&NC initially operated as an independent carrier, but the Union Pacific Railroad purchased a majority stake in 1898. In 1936, the Union Pacific absorbed the OR&NC completely.

Villard, along with his general agent, Thomas R. Tannatt (head of the Oregon Improvement Company), were directly involved in bringing Volga German settlers to the Pacific Northwest and surely knew that encouraging more of these people to Portland would be a benefit to both his railroad and real estate interests.

Construction of the transcontinental railroad to Portland was celebrated in September 1883, and the first trains running from Portland to Walla Walla began operating in November. Anticipating completion of the line, Henry Villard ordered that a small passenger station be built during the summer of 1883 at a cost of no more than $5,000. The station, located in East Portland at the foot of Cedar Street, was completed by September.

The direct railway connection to the Midwest and Eastern United States spurred additional growth in Albina and facilitated increased migration of Volga Germans to Albina.

The 1884 Sanborn Insurance Map of Albina shows that the primary businesses included the seven-story Portland Flouring Mills (incorporated by William S. Ladd), Albina Sawing and Planing Mills, Oregon Iron Works, the Montgomery grain dock, and the OR&NC rail operations.

By the late 1880s, Albina became the fastest-growing city in Oregon and a company town, the company being the OR&NC. The OR&NC was founded by Henry Villard. Villard was also President of the Northern Pacific Railroad and a real estate investor in Albina. He had many connections with the influential businessmen in Portland. The OR&NC initially operated as an independent carrier, but the Union Pacific Railroad purchased a majority stake in 1898. In 1936, the Union Pacific absorbed the OR&NC completely.

Villard, along with his general agent, Thomas R. Tannatt (head of the Oregon Improvement Company), were directly involved in bringing Volga German settlers to the Pacific Northwest and surely knew that encouraging more of these people to Portland would be a benefit to both his railroad and real estate interests.

Anticipating the real estate boom resulting from the railroad expansion in 1882, developers advertised 480 lots in the recently platted Albina Homestead tract. The development was said to be "situated next to Albina (at that time referring to the original townsite platted in 1873). The advertisement stated that "the streets are wide and have been cleared, while the lots are high and level and can be cleared very easily."

Real estate agents tempted potential buyers to act quickly by urging them to acquire "a limited number of these Lots and Blocks at reasonable prices and on easy terms." One advertisement went on to extoll the unique virtues of the Albina Homestead development.

Real estate agents tempted potential buyers to act quickly by urging them to acquire "a limited number of these Lots and Blocks at reasonable prices and on easy terms." One advertisement went on to extoll the unique virtues of the Albina Homestead development.

THE ALBINA HOMESTEAD is unquestionably the best field for investment and the most desirable place for location now on the market. Its close proximity to the cities of Portland and East Portland, and to the heavy improvements now being carried out by the various companies under the direction of Mr. Villard -- the Dry Docks, Elevators, Machine Shops and other works of these companies -- its nearness to the Albina Ferry, together with the proposed Street Railway from L Street Ferry, in East Portland, will make this property very accessible for all part of these cities. These advantages will necessarily attract a large population, and in the meantime make this the most popular and valuable suburban property in this vicinity, while in the near future it must furnish homes for the rapidly increasing population of Albina, and then its value will be at least five times what we now offer for it. We will show the property and give full information to all who may apply to us personally, and inquiries addressed to us by mail will receive prompt attention.

E. J. Haight & Co. Real Estate Agents, 52 Morrison street, and Lownsdale & Co. Real Estate Agents, 6 Washington st. Portland, Or.

City directories show that during the first decade of settlement, beginning in 1881, most Volga German households were in the original Albina townsite platted in 1873. Over time, many began to build or buy homes in the Albina Homestead, Central Albina, and Multnomah plats that were all developed in the 1880s.

The population continued to grow, and the boundaries of Albina expanded to the north and east. The Lincoln Park, North Irvington, and Lincoln Park Annex plats were developed to accommodate a surge of immigrants from Europe. Many Volga Germans resided in these plats up to the 1970s. Historian Roy Roos describes his observation of the development pattern.

The population continued to grow, and the boundaries of Albina expanded to the north and east. The Lincoln Park, North Irvington, and Lincoln Park Annex plats were developed to accommodate a surge of immigrants from Europe. Many Volga Germans resided in these plats up to the 1970s. Historian Roy Roos describes his observation of the development pattern.

"The first arrivals were mainly Irish and Germans, separated of course. Then by early 1880s, Scandinavians came who preferred upper subdivisions north of Eliot neighborhood such as along N. Mississippi up to about N. Prescott street. New plats that stretched further out were filed like mad by 1891, even out towards St. Johns past the University of Portland and east of MLK up to Killingsworth, as the Albina city limits expanded. From my findings, most of Russian Germans settled in the area north of Fremont and east of N. Williams Avenue out in the Lincoln Park subdivision (south of NE Prescott street). This area was more sparsely settled early and it is likely the reason they preferred it. The lots were cheaper too."

1902 map showing the predominant Volga German settlement area in the Albina district of Portland. Both the Albina Homestead and Lincoln Park additions are labeled. Source: Map of Portland, Oregon dated 1902, published by The Title Guarantee & Trust Co. and compiled by Huber and Maxwell, Civil Engineers. This map is displayed in the offices of Oregon Blueprint and the image is used with their permission.

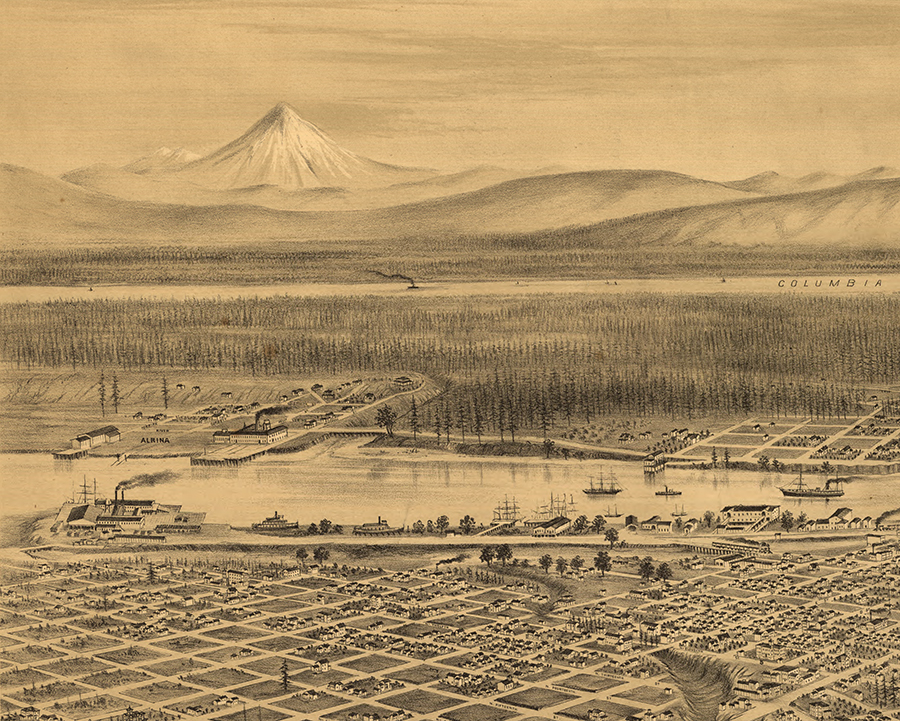

A sketch of the O.R. & N. Co. Dock in 1882. The fledgling community of Albina is shown in the background. Source: Public domain image extracted by Wikimedia Commons from page 62 of The Pacific North-West. A Guide for Settlers and Travelers. Oregon and Washington Territory. Original held and digitized by the British Library.

As new families arrived, there was a need to educate their children. In 1884, the Albina School House was opened on Russell between Williams and Vancouver. In the coming years, the school was expanded, and new schools were built to accommodate the growing number of pupils.

From 1887 until 1891, Albina city ordinances primarily addressed the economic interests of the railroad and other large investors. Gas, electric, and trolley services were extended from downtown Portland on the west side to Albina.

In April 1887, The Oregonian reported that Albina was growing rapidly and quoted William Killingsworth, a major residential real estate investor in Albina:

"Albina has been selected as the place to build industrial enterprises."

The City of Albina was formally incorporated in 1887, one of several independent cities along the Willamette River, hoping to gain prominence. The charter of incorporation envisioned boulevards and magnificent parks. As late as 1903, the notable landscape architect John Olmstead proposed a river bluff park for the North Albina district. These dreams were never realized as the controlling corporate interests had no desire to assume the necessary tax burdens.

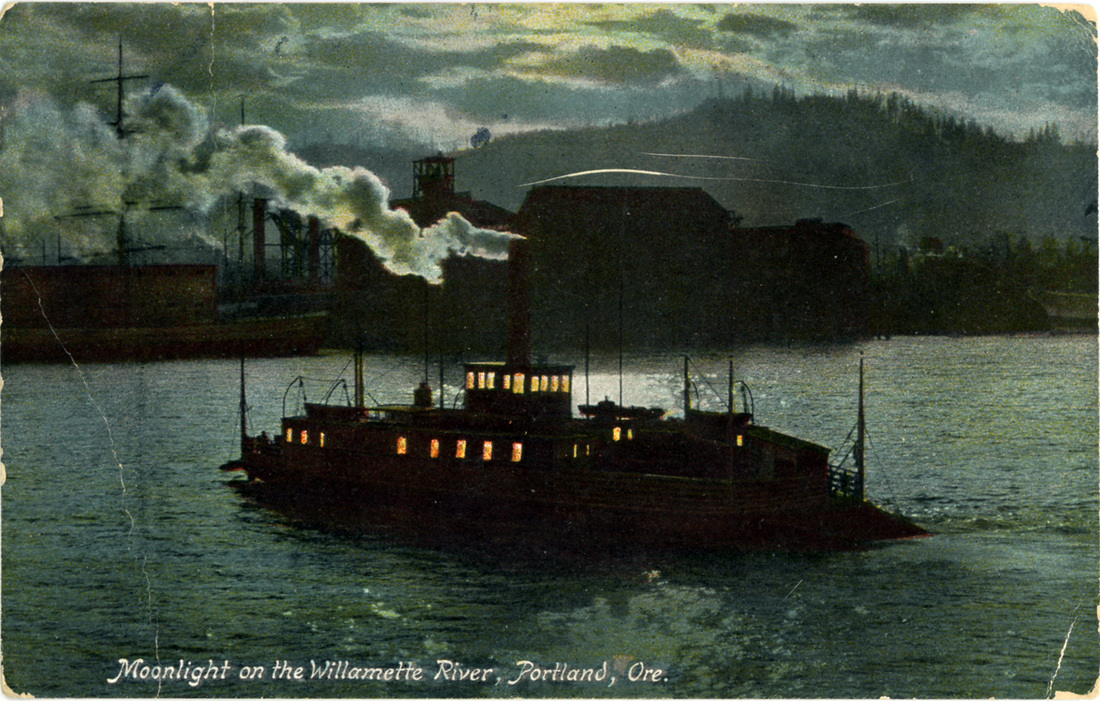

Before the opening of the Morrison Bridge in 1887, some parts of lower Albina were uninhabited wetlands, and the city was connected to the settlements in Portland, Sellwood, Milwaukie, and Oregon City by two ferries and an assortment of small boats. One ferry operated from the foot of Albina Street to Union Station and the other from Russell Street to Fifteenth Street. The population in Albina continued to rise, as did land prices, quadrupling in the first decade of the 20th century. By 1888, the population of Albina had grown to 3,000 people.

Before the opening of the Morrison Bridge in 1887, some parts of lower Albina were uninhabited wetlands, and the city was connected to the settlements in Portland, Sellwood, Milwaukie, and Oregon City by two ferries and an assortment of small boats. One ferry operated from the foot of Albina Street to Union Station and the other from Russell Street to Fifteenth Street. The population in Albina continued to rise, as did land prices, quadrupling in the first decade of the 20th century. By 1888, the population of Albina had grown to 3,000 people.

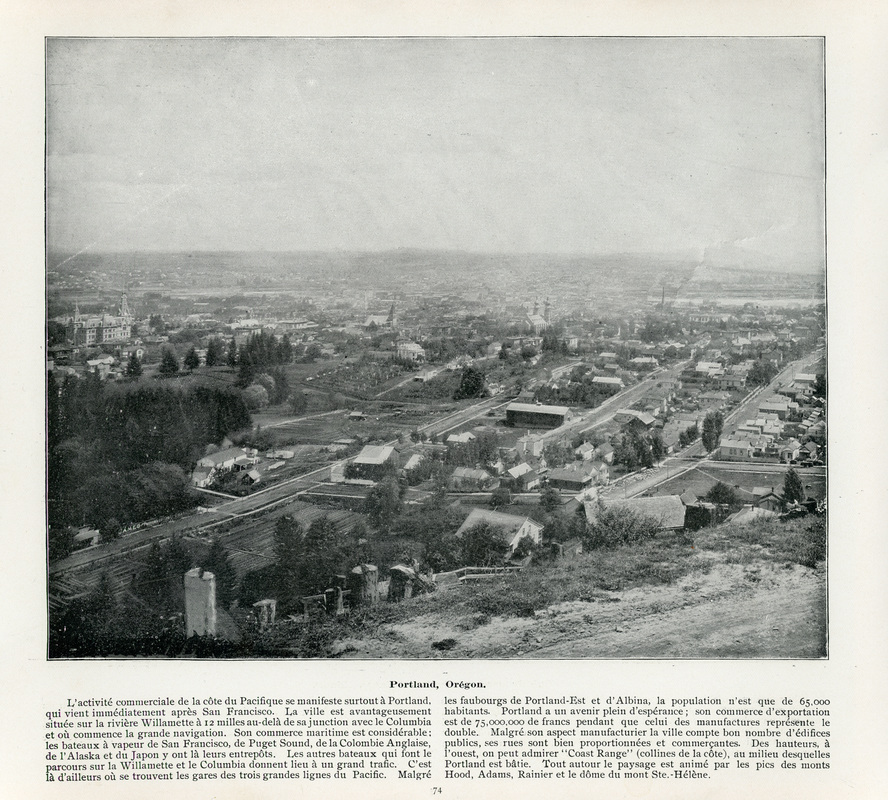

The selection of Albina as an area for industrial development was made by Portland's westside powers, who worked hand in hand with the banks, transit, and utility companies and with the support of local government. The Oregonian newspaper reported on July 18, 1888, that Albina and East Portland were "nearly touching each other."

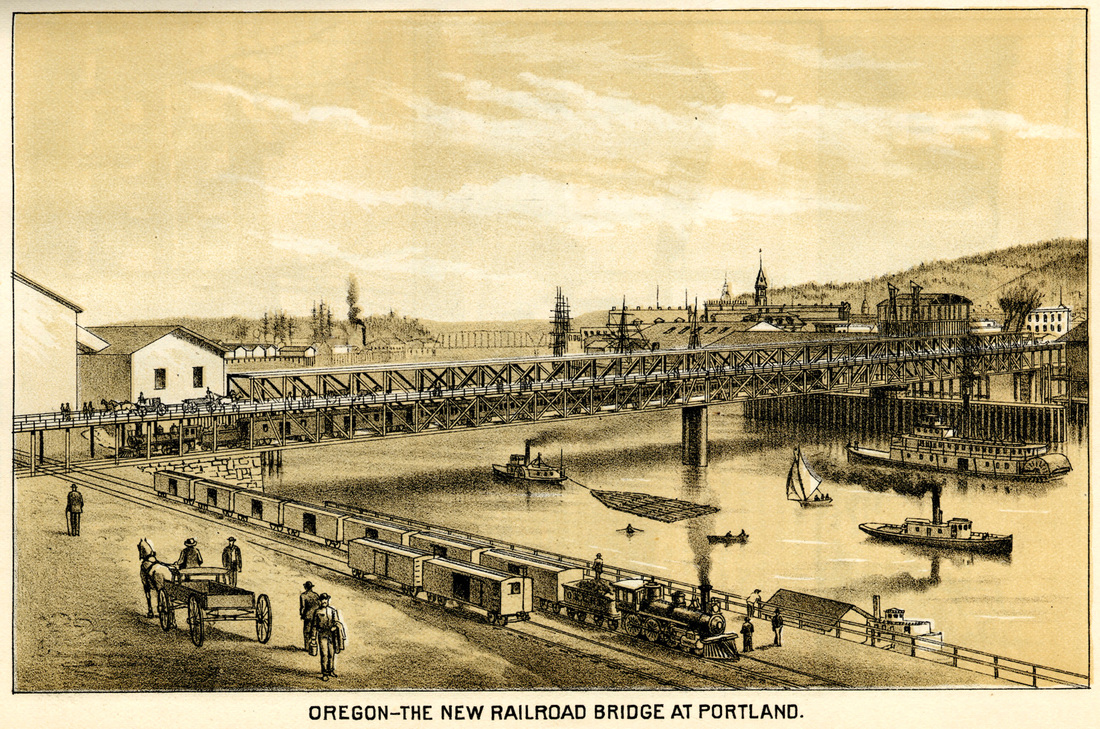

In 1889, Albina annexed the land north to Killingsworth Street and east to 24th. The O.R. & N. Co. completed the Steel Bridge and Willamette Bridge Railway (WBR) that same year. The WBR, owned by the Portland entrepreneur Charles F. Swigert, ran electric streetcars over the bridge between Portland and Albina. The WBR was the first of many electric streetcar lines to open in Portland. The people of Albina celebrated the opening of the bridge which greatly simplified travel to Portland.

In 1889, Albina annexed the land north to Killingsworth Street and east to 24th. The O.R. & N. Co. completed the Steel Bridge and Willamette Bridge Railway (WBR) that same year. The WBR, owned by the Portland entrepreneur Charles F. Swigert, ran electric streetcars over the bridge between Portland and Albina. The WBR was the first of many electric streetcar lines to open in Portland. The people of Albina celebrated the opening of the bridge which greatly simplified travel to Portland.

A drawing of the first Steel Bridge, depicted in December 1887 before the bridge actually went into service linking Portland with Albina (shown in the foreground). Trains crossed the Willamette River on the lower level of the bridge, and pedestrians, carriages and wagons crossed on the upper level. This bridge was replaced in 1912 with the Steel Bridge that remains in service today. Source: "The West Shore." This image is in the Public Domain.

According to the February 15, 1890 Albina Weekly Courier, the city continued to grow rapidly and haphazardly:

"One of the great blemishes of our great city is her short, jagged streets, many of which begin nowhere and end nowhere. The owners of the various additions [to Albina] have laid out their streets regardless of neighboring additions. There are now 25 additions to the original Albina townsite." |

In 1891, growth continued as the City of Albina annexed everything north to Columbia Boulevard and west to the Portsmouth area. Most of Albina at that time was unplatted farmland. It is important to note that Albina remained an independent municipality, with the City of Portland being entirely confined to the west bank of the Willamette River. Over 6,000 people were living in Albina at this time, about ten percent of the region's population.

To acknowledge the frequent and integral connections between activities on both sides of the Willamette, voters in Albina, East Portland, and Portland were asked in 1891 to vote on a measure to consolidate the three municipalities into one city. Economic interests strongly favored consolidation. The results of the consolidation vote showed 10,126 people in support and 1,714 against the measure. The Oregonian was especially impressed by the large voter turnout and the importance that downtown businessmen placed on approval of the measure. Several Portland businesses, such as William S. Ladd's Portland Flouring Mills and Henry Villard's OR&NC, owned nearly two miles of waterfront in Albina. These businesses and their owners would benefit from having political and financial power centralized under the City of Portland. It is not surprising that Villard served in the State House of Representatives in 1891 and promoted consolidation.

With the consolidation measure approved, Portland’s land area increased to twenty-six square miles, and its population grew to at least 63,000. At the time of consolidation in July 1891, Albina’s land area covered thirteen and a half square miles, including St. Johns, more land than Portland and East Portland combined.

Just days before Albina’s planned incorporation into the city of Portland was finalized, Albina’s city council hurriedly passed ordinances and signed contracts for such expenditures as paved roads, city parks, and lighting, which benefited property owners but created a financial burden for the taxpayers of the newly combined city.

The streets in Albina were laid out in the "Philadelphia pattern," with numbered streets paralleling the Willamette River and named streets running east to west. Many street names were changed beginning in 1892 because of duplication in the three consolidated cities. Another major street plan change was made in 1931, creating the system now used in Portland. This system established 100 numbers to the block and five geographic regions (N, NE, SE, NW, and SW). Portland's address style that places the geographic designation between the house number and street name (rather than following the street name as in Seattle) was also established at this time.

Just days before Albina’s planned incorporation into the city of Portland was finalized, Albina’s city council hurriedly passed ordinances and signed contracts for such expenditures as paved roads, city parks, and lighting, which benefited property owners but created a financial burden for the taxpayers of the newly combined city.

The streets in Albina were laid out in the "Philadelphia pattern," with numbered streets paralleling the Willamette River and named streets running east to west. Many street names were changed beginning in 1892 because of duplication in the three consolidated cities. Another major street plan change was made in 1931, creating the system now used in Portland. This system established 100 numbers to the block and five geographic regions (N, NE, SE, NW, and SW). Portland's address style that places the geographic designation between the house number and street name (rather than following the street name as in Seattle) was also established at this time.

The first known Portland fire station protecting the area, known as Chemical 4, was located at 1027 N Union Avenue (now 5035 NE MLK Blvd.). The station name of Chemical derives from the use of horse-drawn engines that used chemicals to propel water from a tank. They were used sparingly in the early 1900s in Portland. This station was originally a wooden building. In 1924, a bungalow-style station was built, and it would remain until the modernization program provided a new Station 14 at 19th and Killingsworth. Neither building exists any longer.

Streetcar lines were extended through Albina prompting housing developments and businesses to spring up along them. There were over 270 miles of streetcar lines in Portland. Many lines were privately operated until Portland Railway Light & Power had consolidated most of them by 1918.

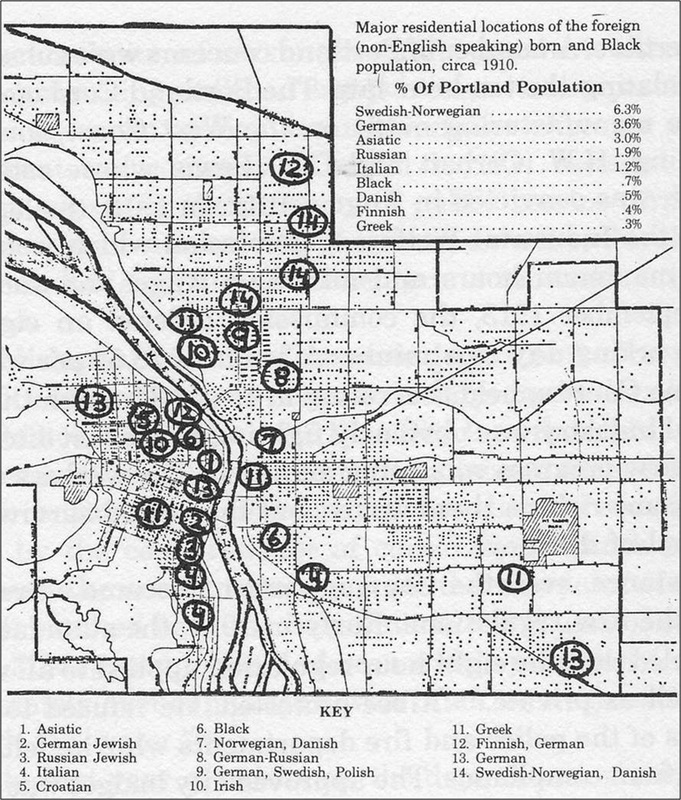

By 1910, the population on the east side of Portland reached 120,000. Portland's total population reached nearly 200,000 by 1912, in large measure due to growth on the east side of the Willamette River. Many ethnic groups were represented throughout the city and in the Albina district.

Streetcar lines were extended through Albina prompting housing developments and businesses to spring up along them. There were over 270 miles of streetcar lines in Portland. Many lines were privately operated until Portland Railway Light & Power had consolidated most of them by 1918.

By 1910, the population on the east side of Portland reached 120,000. Portland's total population reached nearly 200,000 by 1912, in large measure due to growth on the east side of the Willamette River. Many ethnic groups were represented throughout the city and in the Albina district.

The ethnic settlements map is from E. Kimbark MacColl's book The Shaping of the City, p.463. MacColl credits the sources as a Portland Public Schools Annual Report, and Ethnicity in Portland, 1859-1970, A Brief Demographic History to be published in 1976 by the Center for Urban Education. The German-Russian population circa 1910 is indicated on the map by the circled number 8.

During two periods of intense construction activity, 1905-13 and 1922-28, over 20,000 homes were built in Albina, mainly in the bungalow style.

The Albina Pioneer Association was founded on February 21, 1923. The association disbanded on August 1, 1965, but before that time was instrumental in placing a monument in Dawson Park to commemorate the early settlers of the area (those who lived in the district before 1893).

The number of African-Americans living in Albina was relatively small until World War II when more significant numbers moved to Portland to support the war effort, primarily working in the Kaiser and Oregon shipbuilding yards. In 1942, an extensive wartime housing development called Vanport was built in North Portland to house shipyard workers, including many recently arrived blacks. After the war, many of these workers left Portland due to lack of work and job discrimination.

The Vanport flood of 1948 resulted in relocating the remaining African-American population in Vanport (about 25 percent of the 40,000 inhabitants) to the Albina area. These people were not given a choice to live in other parts of Portland because of "redlining" practices meant to keep African-Americans out of other parts of Portland. The term is said to have received its name from bank officials who would hang up maps and draw red circles around minority neighborhoods to avoid investing in them. The City of Portland did not challenge this practice. The rapid change in the racial mixture of Albina created tension in the community.

With the construction of the Memorial Coliseum in February 1959 and the significant displacement of many people in the community caused by the Interstate 5 project through Portland in the 1960s, more blacks living in these areas were forced to move into predominantly white neighborhoods in Albina.

The Albina Pioneer Association was founded on February 21, 1923. The association disbanded on August 1, 1965, but before that time was instrumental in placing a monument in Dawson Park to commemorate the early settlers of the area (those who lived in the district before 1893).

The number of African-Americans living in Albina was relatively small until World War II when more significant numbers moved to Portland to support the war effort, primarily working in the Kaiser and Oregon shipbuilding yards. In 1942, an extensive wartime housing development called Vanport was built in North Portland to house shipyard workers, including many recently arrived blacks. After the war, many of these workers left Portland due to lack of work and job discrimination.

The Vanport flood of 1948 resulted in relocating the remaining African-American population in Vanport (about 25 percent of the 40,000 inhabitants) to the Albina area. These people were not given a choice to live in other parts of Portland because of "redlining" practices meant to keep African-Americans out of other parts of Portland. The term is said to have received its name from bank officials who would hang up maps and draw red circles around minority neighborhoods to avoid investing in them. The City of Portland did not challenge this practice. The rapid change in the racial mixture of Albina created tension in the community.

With the construction of the Memorial Coliseum in February 1959 and the significant displacement of many people in the community caused by the Interstate 5 project through Portland in the 1960s, more blacks living in these areas were forced to move into predominantly white neighborhoods in Albina.

These changes ran in parallel with the national African-American Civil Rights Movement.

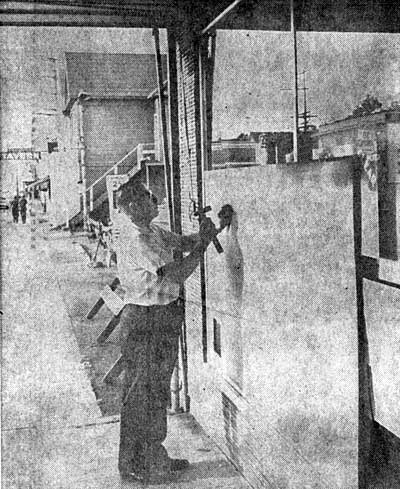

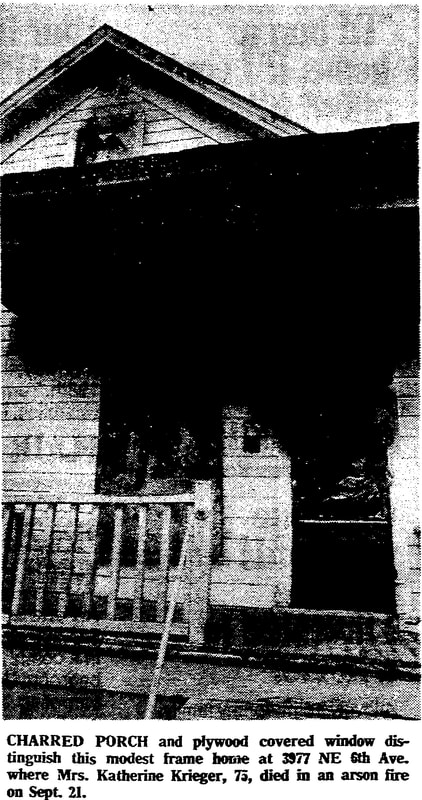

A political rally at Irving Park to encourage "revolution" in the African-American community turned violent during the riots of August 1967. Mayor Terry Shrunk and Governor Tom McCall requested that the National Guard and State Police be ready to intervene if the situation could not be managed alone by the Portland Police. Volga German businesses were damaged during this disturbance (some by firebombs). The riots were followed by continued unrest in the area for several years. More violence in 1969 and 1970 damaged long-established businesses such as Repp Bros. Grocery and Market, Weimer's Furniture and Hardware, Geist Clothing, and Lincoln Park Grocery, owned by Adam Bihn. On September 21, 1970, Mrs. Katherine Krieger (née Block) died in an arson fire allegedly caused by the Black Panthers. Several of her African-American neighbors attempted to save her, but it was too late. The crime was never solved. A series of arson attacks on businesses on Union Avenue between NE Fremont and Russell caused many owners to close or relocate. "It's fear, pure and simple." said one business leader. "It's the ever-present fear day to day -- reading in the paper where someone got it, the fire, the holdup, the bomb." Another businessman stated, "There are some 40 businesses that would like to move out of the area because of the ever-present fear of firebombing." The repeated acts of arson and violence spurred many businesses to close and long-time residents to move to the suburbs of east Portland.

A political rally at Irving Park to encourage "revolution" in the African-American community turned violent during the riots of August 1967. Mayor Terry Shrunk and Governor Tom McCall requested that the National Guard and State Police be ready to intervene if the situation could not be managed alone by the Portland Police. Volga German businesses were damaged during this disturbance (some by firebombs). The riots were followed by continued unrest in the area for several years. More violence in 1969 and 1970 damaged long-established businesses such as Repp Bros. Grocery and Market, Weimer's Furniture and Hardware, Geist Clothing, and Lincoln Park Grocery, owned by Adam Bihn. On September 21, 1970, Mrs. Katherine Krieger (née Block) died in an arson fire allegedly caused by the Black Panthers. Several of her African-American neighbors attempted to save her, but it was too late. The crime was never solved. A series of arson attacks on businesses on Union Avenue between NE Fremont and Russell caused many owners to close or relocate. "It's fear, pure and simple." said one business leader. "It's the ever-present fear day to day -- reading in the paper where someone got it, the fire, the holdup, the bomb." Another businessman stated, "There are some 40 businesses that would like to move out of the area because of the ever-present fear of firebombing." The repeated acts of arson and violence spurred many businesses to close and long-time residents to move to the suburbs of east Portland.

Below is a video documentary produced by Oregon Public Broadcasting about the Civil Rights movement in Portland. There is a very interesting quote in this video about the black population in Albina viewing themselves as "an internal colony." The Volga Germans saw themselves similarly when they first arrived in 1881. This feeling persisted until the 1950s when they began to assimilate and disperse throughout the metropolitan area.

By the early 1970s, African Americans comprised the majority of the population in the Albina area, and little evidence remained of what had once been Little Russia. As African Americans fought for a fair and just place in society, the assimilation and dispersion of the Volga German community in Portland was nearly complete.

The individual neighborhoods of the current Albina area are as diverse as the people who live there. Some of these areas have identities that go back 100 years, while others obtained their current names and boundaries with the advent of formal neighborhood

associations in Portland during the 1960s and 1970s. The neighborhood associations have names and boundaries more often reflecting school district designations than their historic origins. Over time, some names have faded, and histories of neighborhoods in Albina often overlap.

associations in Portland during the 1960s and 1970s. The neighborhood associations have names and boundaries more often reflecting school district designations than their historic origins. Over time, some names have faded, and histories of neighborhoods in Albina often overlap.

Beginning in the late 1990s, the Albina neighborhood began yet another transition as young, primarily white professionals moved into the neighborhood in what has become known as gentrification. Since then, housing prices have dramatically increased in most of inner-east Portland. Much of the African-American population in Albina has shifted north and east toward the Columbia River and Gresham, following the same movement pattern as many Volga Germans in the 1960s and 1970s.

Sources

Abbott, Carl. Portland: Gateway to the Northwest. Northridge, CA: Windsor Publications, 1985. Print.

Bryan, Joshua Joe. Portland, Oregon's Long Hot Summers: Racial Unrest and Public Response, 1967 - 1969. Thesis. Portland State University, 2013. Portland: Portland State U, 2013. Print.

Craighead, Alexander B. Railway Palaces of Portland, Oregon. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2016. Print.

Harper, Will. History of Albina. Comprehensive Planning Workshop Publication. Portland, Oregon: Portland State University, 1990. Print. (Note: Volga German descendant Hannah Deines was interviewed for this publication.)

MacColl, E. Kimbark. The Shaping of a City: Business and Politics in Portland, Oregon, 1885-1915. Portland, Or.: Georgian, 1976. Print.

Roos, Roy E. The History of Albina: Including Eliot, Boise, King, Humboldt, and Piedmont Neighborhoods. Portland, Oregon: 2008. Print.

Roos, Roy E. Albina area (Portland), The Oregon Encyclopedia.

"Albina. (Opposite Portland.)." The Oregonian [Portland}, July 22, 1876. page 2.

"The O. R. and N. Co.'s Terminus. Work At Albina To Be Commerced Next Week". The Morning Oregonian [Portland], March 8, 1882.

"Albina. The Actual Terminus of Our Railway System." The Oregonian [Portland}, November 27, 1882.

"Arson Held Primary Cause of Dwindling Economy of Albina." The Sunday Oregonian [Portland}. October 18, 1970. page 38.

"News From The East Side Albina and East Portland Nearly Touching Each Other." The Morning Oregonian [Portland], July 18, 1888. page 8.

"The East Side. Great Improvements Have Been Made In Every Quarter." The Oregonian [Portland], November 4, 1892, page 8.

"Troubled Times in Albina - Signs Point To Urban Wasteland As Troubled Area Loses Stores." The Oregonian, Thursday, June 19, 1969, page 14.

Portland Fire History website. https://www.portlandfirehistory.com/stations Accessed 21 February 2022.

Bryan, Joshua Joe. Portland, Oregon's Long Hot Summers: Racial Unrest and Public Response, 1967 - 1969. Thesis. Portland State University, 2013. Portland: Portland State U, 2013. Print.

Craighead, Alexander B. Railway Palaces of Portland, Oregon. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2016. Print.

Harper, Will. History of Albina. Comprehensive Planning Workshop Publication. Portland, Oregon: Portland State University, 1990. Print. (Note: Volga German descendant Hannah Deines was interviewed for this publication.)

MacColl, E. Kimbark. The Shaping of a City: Business and Politics in Portland, Oregon, 1885-1915. Portland, Or.: Georgian, 1976. Print.

Roos, Roy E. The History of Albina: Including Eliot, Boise, King, Humboldt, and Piedmont Neighborhoods. Portland, Oregon: 2008. Print.

Roos, Roy E. Albina area (Portland), The Oregon Encyclopedia.

"Albina. (Opposite Portland.)." The Oregonian [Portland}, July 22, 1876. page 2.

"The O. R. and N. Co.'s Terminus. Work At Albina To Be Commerced Next Week". The Morning Oregonian [Portland], March 8, 1882.

"Albina. The Actual Terminus of Our Railway System." The Oregonian [Portland}, November 27, 1882.

"Arson Held Primary Cause of Dwindling Economy of Albina." The Sunday Oregonian [Portland}. October 18, 1970. page 38.

"News From The East Side Albina and East Portland Nearly Touching Each Other." The Morning Oregonian [Portland], July 18, 1888. page 8.

"The East Side. Great Improvements Have Been Made In Every Quarter." The Oregonian [Portland], November 4, 1892, page 8.

"Troubled Times in Albina - Signs Point To Urban Wasteland As Troubled Area Loses Stores." The Oregonian, Thursday, June 19, 1969, page 14.

Portland Fire History website. https://www.portlandfirehistory.com/stations Accessed 21 February 2022.

Last updated October 21. 2023