Beliefs > The Brethren

The Brethren

In addition to the primary religious denominations, an early pietistic movement evolved into an organized body of considerable strength and influence in the Volga German colonies. Der Brüderschaft Versammlung, known as the "Brotherhood," or more commonly the "Brethren" movement, might be described as an auxiliary to the Protestant churches.

The Brethren were part of the Stundist revival movement that began with the German settlers living in South Russia. The movement takes its name from the Stunde or devotional "hour," in which adherents would gather in homes to sing, pray, and read scripture. The movement emphasized individual moral and spiritual regeneration, cultivating an inner spiritual life and rejecting material pleasures.

The Brethren were part of the Stundist revival movement that began with the German settlers living in South Russia. The movement takes its name from the Stunde or devotional "hour," in which adherents would gather in homes to sing, pray, and read scripture. The movement emphasized individual moral and spiritual regeneration, cultivating an inner spiritual life and rejecting material pleasures.

Rev. Wilhelm Stärkel from the colony of Norka was one of the few Volga German clerics who supported the Brethren movement in Russia. Many of his colleagues tried to suppress the Brethren, resulting in tensions between lay people and the clergy. For some, these tensions prompted immigration to the United States and Canada.

Along with Rev. Stärkel, the evangelists Heinrich Peter Ehlers and Johannes Koch were the three principal leaders of the Brotherhood movement amongst the Volga colonists. All three men were ardent Millennialists and took an active role in the Zionist movement of their day, lecturing on its behalf and supporting it financially. Author George Eisenach characterizes them as "fanatic in their support of this doctrine." Johannes Koch was ordained in 1888 after he arrived in the United States. Given that many of the people in Portland had known evangelist Johannes Koch in Russia, it is clear why he was called to establish the Ebenezer German Congregational Church, the mother congregational church for the Volga Germans in Portland.

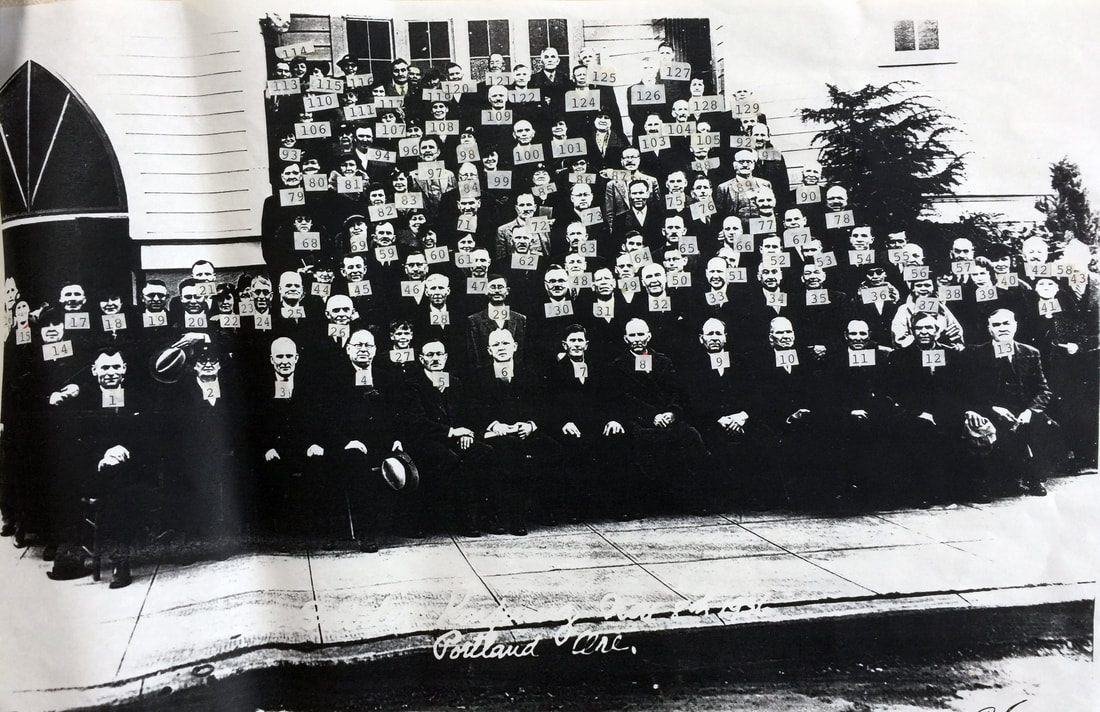

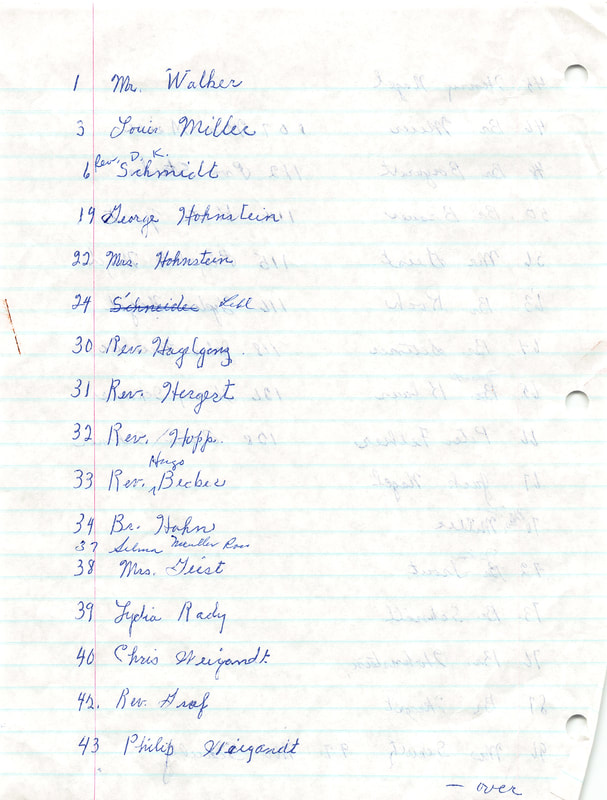

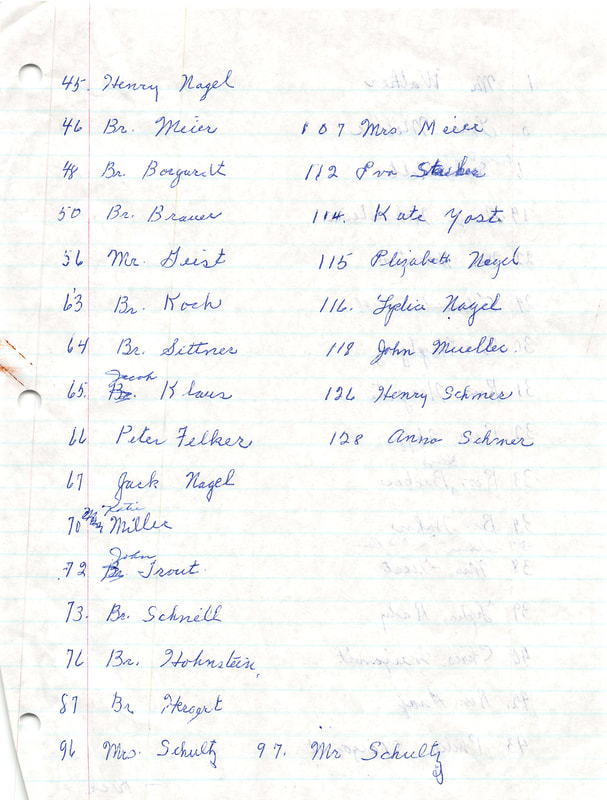

Because of Rev. Stärkels' support, many people in Norka belonged to the Brethren. Once a year, there was a minor regional parish conference for the Brethren. Likewise, there were two large general conferences, one each on the Bergseite (hilly side of the Volga River) and the Wiesenseite (meadow side), which are always held in Norka and in Brunnental (a daughter colony of Norka). Many people from Norka and Brunnental immigrated to the United States and became leaders in founding many of the Volga German churches in Portland. The Brethren conferences continued in the United States, including several in Portland.

Although the Brethren organized private prayer circles and Bible study, they simultaneously participated in all the church functions. They put into practice the theory of the priesthood of all believers. Almost without exception, Brethren members were the nucleus of the individual church organizations and directed their development.

The main difference when compared to the teaching of the Evangelische Kirche (Lutheran church) is the very prominent place the Brethren gave to the prophetic books of the Old and New Testaments and, therefore, also to the teaching of millennialism, a belief strongly supported by Rev. Stärkel who wrote a book on this topic.

The primary organization of the Brethren was the local prayer meeting. These meetings, which were instituted on behalf of practical piety, were led and directed by laymen. The meetings were held four times a week—Wednesday evening, Saturday evening, Sunday afternoon, and Sunday evening. A Christian bond of union arose among those who met four times a week to hear God's Word, to confess their sins, to give their testimonies, and to tell of their spiritual triumphs. There, they rejoiced with those who rejoiced and wept with those who wept. Bound together by common spiritual aspirations, these circles of pious friends and steadfast companions watched over each other and helped bear one another's burdens.

The elders appointed three Brethren to lead the group at each prayer meeting. In their addresses, the leaders frequently referred to their own conversion and laid down the fundamental premise that all who wished to be saved must be born again. The listeners were made supremely aware of the danger of a literal hell and told of the horror of everlasting punishment. They condemned this world and thought only of the next.

The Brethren quoted numerous Bible passages in support of their views. The singing of revival hymns was a conspicuous part of the meeting, even before its opening. Necessity forced the adoption of "lining" the hymns, for the whole group possessed only a few copies of each German hymn book. The lines, read by one of the leaders and repeated in song by the group, proved of great value because the converts thereby memorized hundreds of sacred songs.

The prayer meeting was a place where plainness of dress was the rule. Every individual was met and greeted with heartfelt interest. The story of trouble was heard with deep sympathy. No formality could exist where such feeling reigned. No effort was needed to draw people together. In Russia, private homes generally served as the meeting places. In some villages, modest prayer-meeting halls were erected.

The women, known as Sisters, occupied separate pews and were generally silent during the meetings. Upon entering the prayer meeting hall, one would see all the men seated in the pews on the left and all the women sitting in the pews on the right with their heads covered. Songs are sung about 15 minutes before the appointed time for the official opening. After that, the elders ask the Brethren to "go forward." The first named person takes his place at the center chair and takes charge of the meeting. He opens the meeting by announcing a hymn from the Wolga Gesangbuch (Volga Songbook), the church hymnal used in the Lutheran Church among the Volga colonists in Russia. He "lines" the hymn for the audience. Following the hymn, he leads in prayer with the converts kneeling. Without any announcement, someone in the audience starts a song, which is taken up by the assembled group. While a few verses are being sung, the center leader chooses the text, usually from eight to twelve verses in length. Following the Scripture reading, selected on the spot, a song is sung appropriate to the ideas of the text, and he makes timely applications from it.

At the close of his address, an appropriate song is sung, after which either the Brother to the right or left of the main leader brings his message. He uses the same text and devotes eight to ten minutes to his remarks. He frequently begins by saying that what has been said is in harmony with God's Holy Word. His speech is followed by a few stanzas of a hymn and that, in turn, by the discourse of the other Brother. The meetings, which last an hour and a half or even longer, are closed officially with the Lord's Prayer recited by all.

In 1888, the Czarist government banned Stundism and began prosecuting its believers. This act undoubtedly prompted more Volga Germans to emigrate from Russia. The Brethren movement continued in many areas where immigrants settled in the New World. In Portland, the names of several churches founded by Volga German immigrants referenced the Brethren movement (the German Congregational Evangelical Brethren Church and the Free Evangelical Brethren Church). Nearly all of the Volga German congregations in Portland held Brethren meetings, some until the 1990s.

Along with Rev. Stärkel, the evangelists Heinrich Peter Ehlers and Johannes Koch were the three principal leaders of the Brotherhood movement amongst the Volga colonists. All three men were ardent Millennialists and took an active role in the Zionist movement of their day, lecturing on its behalf and supporting it financially. Author George Eisenach characterizes them as "fanatic in their support of this doctrine." Johannes Koch was ordained in 1888 after he arrived in the United States. Given that many of the people in Portland had known evangelist Johannes Koch in Russia, it is clear why he was called to establish the Ebenezer German Congregational Church, the mother congregational church for the Volga Germans in Portland.

Because of Rev. Stärkels' support, many people in Norka belonged to the Brethren. Once a year, there was a minor regional parish conference for the Brethren. Likewise, there were two large general conferences, one each on the Bergseite (hilly side of the Volga River) and the Wiesenseite (meadow side), which are always held in Norka and in Brunnental (a daughter colony of Norka). Many people from Norka and Brunnental immigrated to the United States and became leaders in founding many of the Volga German churches in Portland. The Brethren conferences continued in the United States, including several in Portland.

Although the Brethren organized private prayer circles and Bible study, they simultaneously participated in all the church functions. They put into practice the theory of the priesthood of all believers. Almost without exception, Brethren members were the nucleus of the individual church organizations and directed their development.

The main difference when compared to the teaching of the Evangelische Kirche (Lutheran church) is the very prominent place the Brethren gave to the prophetic books of the Old and New Testaments and, therefore, also to the teaching of millennialism, a belief strongly supported by Rev. Stärkel who wrote a book on this topic.

The primary organization of the Brethren was the local prayer meeting. These meetings, which were instituted on behalf of practical piety, were led and directed by laymen. The meetings were held four times a week—Wednesday evening, Saturday evening, Sunday afternoon, and Sunday evening. A Christian bond of union arose among those who met four times a week to hear God's Word, to confess their sins, to give their testimonies, and to tell of their spiritual triumphs. There, they rejoiced with those who rejoiced and wept with those who wept. Bound together by common spiritual aspirations, these circles of pious friends and steadfast companions watched over each other and helped bear one another's burdens.

The elders appointed three Brethren to lead the group at each prayer meeting. In their addresses, the leaders frequently referred to their own conversion and laid down the fundamental premise that all who wished to be saved must be born again. The listeners were made supremely aware of the danger of a literal hell and told of the horror of everlasting punishment. They condemned this world and thought only of the next.

The Brethren quoted numerous Bible passages in support of their views. The singing of revival hymns was a conspicuous part of the meeting, even before its opening. Necessity forced the adoption of "lining" the hymns, for the whole group possessed only a few copies of each German hymn book. The lines, read by one of the leaders and repeated in song by the group, proved of great value because the converts thereby memorized hundreds of sacred songs.

The prayer meeting was a place where plainness of dress was the rule. Every individual was met and greeted with heartfelt interest. The story of trouble was heard with deep sympathy. No formality could exist where such feeling reigned. No effort was needed to draw people together. In Russia, private homes generally served as the meeting places. In some villages, modest prayer-meeting halls were erected.

The women, known as Sisters, occupied separate pews and were generally silent during the meetings. Upon entering the prayer meeting hall, one would see all the men seated in the pews on the left and all the women sitting in the pews on the right with their heads covered. Songs are sung about 15 minutes before the appointed time for the official opening. After that, the elders ask the Brethren to "go forward." The first named person takes his place at the center chair and takes charge of the meeting. He opens the meeting by announcing a hymn from the Wolga Gesangbuch (Volga Songbook), the church hymnal used in the Lutheran Church among the Volga colonists in Russia. He "lines" the hymn for the audience. Following the hymn, he leads in prayer with the converts kneeling. Without any announcement, someone in the audience starts a song, which is taken up by the assembled group. While a few verses are being sung, the center leader chooses the text, usually from eight to twelve verses in length. Following the Scripture reading, selected on the spot, a song is sung appropriate to the ideas of the text, and he makes timely applications from it.

At the close of his address, an appropriate song is sung, after which either the Brother to the right or left of the main leader brings his message. He uses the same text and devotes eight to ten minutes to his remarks. He frequently begins by saying that what has been said is in harmony with God's Holy Word. His speech is followed by a few stanzas of a hymn and that, in turn, by the discourse of the other Brother. The meetings, which last an hour and a half or even longer, are closed officially with the Lord's Prayer recited by all.

In 1888, the Czarist government banned Stundism and began prosecuting its believers. This act undoubtedly prompted more Volga Germans to emigrate from Russia. The Brethren movement continued in many areas where immigrants settled in the New World. In Portland, the names of several churches founded by Volga German immigrants referenced the Brethren movement (the German Congregational Evangelical Brethren Church and the Free Evangelical Brethren Church). Nearly all of the Volga German congregations in Portland held Brethren meetings, some until the 1990s.

Sources

Eisenach, George J. Pietism and the Russian Germans in the United States. Berne, IN: Berne, 1948. Print.

Eisenach, George J. A History of the German Congregational Churches in the United States. Yankton, SD: Pioneer, 1938. Print.

Gaus, Alex, comp. The German Brotherhood: 254 Years of History from the Volga River in Russia, U.S.A., Canada, South America, and Siberia. Flint, MI: S.n., 1977. Print.

Koehler, Paul. "The German Brotherhood: 272 Years of History." Journal of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia 27.4 (2004): 8-18. Print.

Eisenach, George J. A History of the German Congregational Churches in the United States. Yankton, SD: Pioneer, 1938. Print.

Gaus, Alex, comp. The German Brotherhood: 254 Years of History from the Volga River in Russia, U.S.A., Canada, South America, and Siberia. Flint, MI: S.n., 1977. Print.

Koehler, Paul. "The German Brotherhood: 272 Years of History." Journal of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia 27.4 (2004): 8-18. Print.

Last updated November 16, 2023