Irving Park's Volga German Connection

By Steven SchreiberIn the early days of settlement, the local residents used the open land comprising today's Irving Park as a field for pasturing their horses and cows. Emma Schwabenland Haynes recalls the following story about her grandfather, early Volga German pioneer John O. Miller:

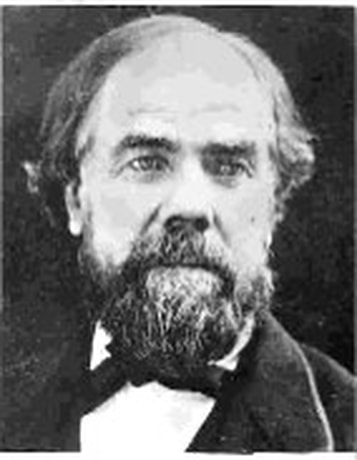

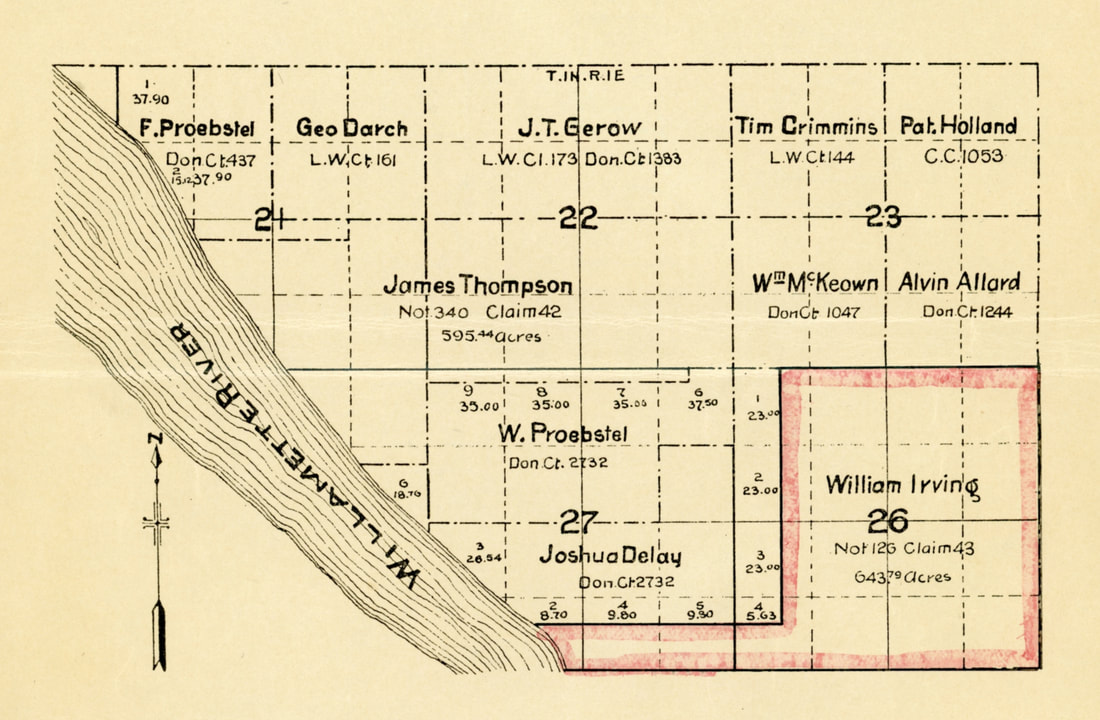

Grandfather's barns were located in back of the Morris Street house, and he took his four Jersey cows to pasture in the blocks where Irving Park is now located. For this privilege he paid a small yearly fee to the owner. These cows were kept until 1908, and constitued his chief source of income until that time. The land had been owned by Captain William Irving, a native of Scotland and famous figure in early Pacific Northwest maritime history, since 1851 - 30 years before the first Volga Germans arrived in Portland. Captain Irving and his new 18-year-old bride, Elizabeth Dixon, were granted a square-shaped donation land claim bounded by Fremont on the North, Tillamook on the South, 7th Avenue on the West, and 24th Avenue on the East. There was also a narrow panhandle strip that ran from what is now Halsey, Broadway, and Schuyler to the Willamette River near the current location of the Broadway Bridge.

|

The Irving land claim at this time had two components: The western half (from 7th to 15th) was in Elizabeth's name and was known as West Irvington. The eastern half was in William Irving's name. The total land claim was 635 acres with 1,600 feet of river frontage and was patented in 1865 and recorded in 1887. At the time of the Irving claim, the land was almost all farms and forests.

To the west of West Irvington was the small town of Albina, which in 1851 consisted primarily of working-class housing represented by one-and-one-half-story late Victorian cottages.

Captain Irving built a large house of redwood in a Gothic style on a rise near the river where he and his wife raised five children: Mary, John, Susan, Elizabeth, and Nellie. A monument near Memorial Coliseum marks the location.

In 1859, the Irving family moved to British Columbia and appointed another boat captain, George Shaver, to manage their property. Married to Sarah Dixon, Shaver was Elizabeth Irving's brother-in-law, and his family moved into the Irving house. Historically, the original Irving house is called the "Shaver House," which no longer exists today.

A second house was built in 1884 that was located near the first, and it was occupied by Irving's daughter, Elizabeth Spencer, and her husband. The "Spencer House" was moved to its current location on NE 12th between Brazee and Knott (2611 N.E. 12th) in 1911 to make room for the Broadway Bridge. Today, the Spencer House is the oldest in the Irvington neighborhood.

Captain Irving became a leading citizen in New Westminster, British Columbia, and died there in 1872 at age 56.

Elizabeth Dixon Irving moved back to Portland a few years later to manage her half of the donation land claim.

Captain Irving's daughter, Elizabeth Irving Spencer, and son, John Irving, sold significant portions of their father's share of the donation land claim. On March 1, 1882, John Irving filed a plat for "John Irving's First Addition to East Portland." On April 21, 1882, he and Elizabeth Dixon Irving sold 288 acres of the donation land claim to their business partners David P. Thompson, Ellis G. Hughes, and John W. Brazee for $62,109. The partners and their subsequent investors, such as Charles Prescott, would work together to develop the area in a relatively uniform fashion.

Captain Irving built a large house of redwood in a Gothic style on a rise near the river where he and his wife raised five children: Mary, John, Susan, Elizabeth, and Nellie. A monument near Memorial Coliseum marks the location.

In 1859, the Irving family moved to British Columbia and appointed another boat captain, George Shaver, to manage their property. Married to Sarah Dixon, Shaver was Elizabeth Irving's brother-in-law, and his family moved into the Irving house. Historically, the original Irving house is called the "Shaver House," which no longer exists today.

A second house was built in 1884 that was located near the first, and it was occupied by Irving's daughter, Elizabeth Spencer, and her husband. The "Spencer House" was moved to its current location on NE 12th between Brazee and Knott (2611 N.E. 12th) in 1911 to make room for the Broadway Bridge. Today, the Spencer House is the oldest in the Irvington neighborhood.

Captain Irving became a leading citizen in New Westminster, British Columbia, and died there in 1872 at age 56.

Elizabeth Dixon Irving moved back to Portland a few years later to manage her half of the donation land claim.

Captain Irving's daughter, Elizabeth Irving Spencer, and son, John Irving, sold significant portions of their father's share of the donation land claim. On March 1, 1882, John Irving filed a plat for "John Irving's First Addition to East Portland." On April 21, 1882, he and Elizabeth Dixon Irving sold 288 acres of the donation land claim to their business partners David P. Thompson, Ellis G. Hughes, and John W. Brazee for $62,109. The partners and their subsequent investors, such as Charles Prescott, would work together to develop the area in a relatively uniform fashion.

|

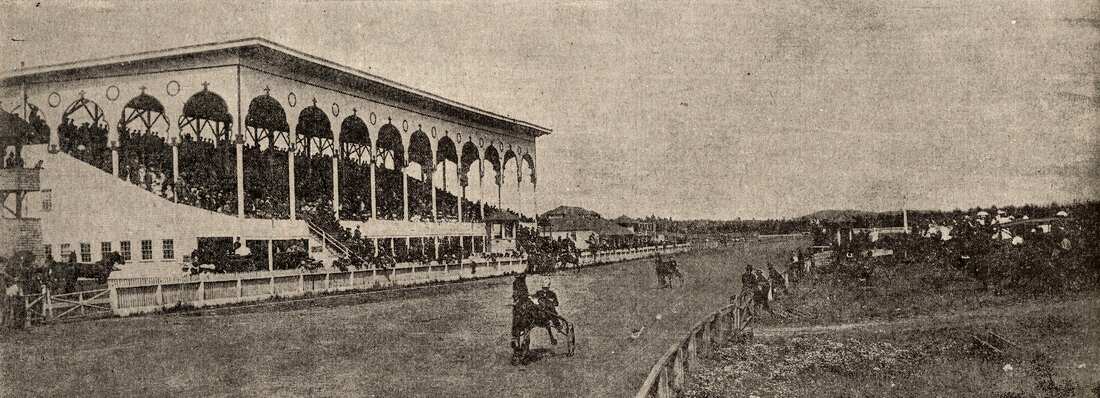

Elizabeth Dixon Irving married A. G. Ryan in 1887 and leased 90 acres in the far northwest corner of her remaining claim to W. S. Dixon for five years. W. S. Dixon was a nephew of Elizabeth's who lived in Vancouver, British Columbia. The lease to Dixon stipulated that no improper, unlawful, or offensive use of the property could be made. Dixon assigned the lease to an innocent-sounding Multnomah Fair Association (MFA). The MFA soon began construction of a race track, grandstands, and paddocks. Many early residents in the Irvington development kept their horses in stables along the north side of the track—stables were not permitted within the neighborhood as stipulated in covenants.

|

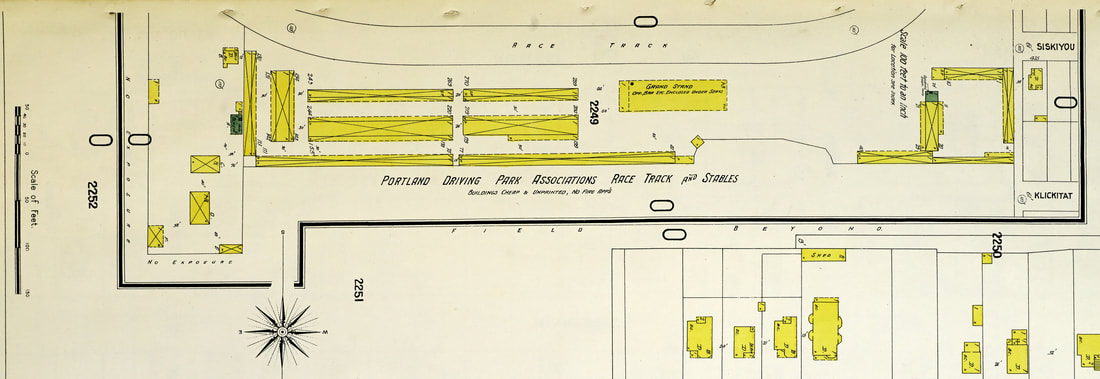

Although known simply as the Irvington racetrack, the formal name was Portland Driving Park Associations Race Track and Stables. The complex occupied the area currently bounded by Fremont on the North, 14th on the East, Russell on the South, and 7th on the West. A large grandstand with a bar and offices underneath was located between the extended lines of Klickitat and Siskiyou streets and 9th and 10th streets. Long rows of stables were situated to the east of the grandstand. To the west of the grandstand was another cluster of stables and a shoeing shop. The 1901 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map includes the note: "Buildings cheap & unpainted, no fire apparatus."

The Irvington track was extremely popular with businessmen who returned to their homes in the area for the weekend but worked downtown during the week. Also, the good streetcar connections allowed many people to attend the races. Crowds numbering 5,000 people attended weekend racing events.

Emma Schwabenland Haynes wrote the following about her memories of the race track which was close to her childhood home:

During the spring of 1895 further changes took place in the Miller neighborhood. All of the land and the four blocks east of the Morris Street house was bought by an investment company for use as a racetrack. Since many of the trees and all the stumps were still standing, dynamite was used to blast them out, and the reverberations were so great that some of grandmother’s dishes fell out of the cupboard and were broken. Also, no baby chickens were hatched that spring because all the eggs were spoiled by the constant shaking of the ground.

For the next ten years the racing season was the most exciting period in the lives of the neighborhood children. They always looked forward to the arrival of the horses and the jockeys, while the crowds of spectators, the peanut stands, the constant gambling and betting, and the music of the gaily uniformed bands, all lent a certain amount of excitement and glamour to their lives. There was never any money with which to buy tickets, but the twins could see the races from the roof of their kitchen, and the two American-born brothers usually managed to carry water to the horses as an admission price. If this was impossible, they would sometimes bore holes under the fence surrounding the track or even shinny up the sides. On other occasions the guards at the gate would allow all the little boys to race from the ticket office to the entrance of the track. The understanding was that the boy who won the race would be allowed to enter free, but it usually happened that the whole group continued running until they arrived safely inside. Countless stories of the race track were often told by Uncle George Repp, Uncle George Miller, Uncle Johnny, Fred Schnell and all the other men who were still boys in the 1890s.

After the races were over and the doors opened, mother, Aunt Katy, and the other girls in the neighborhood scampered to the grandstand as fast as they could, and would run quickly up and down the rows, looking for any money that might have been accidentally dropped. Everything of value was picked up and carried home, and during all of those years, the chief handkerchief supply of the family came from these grandstand seats. The racetrack was also a source of spending money for the boys in the neighborhood because they were allowed to pick up the empty gunny sacks which had been filled with feed for the horses. Two good sacks of this type could always be sold for a nickel.

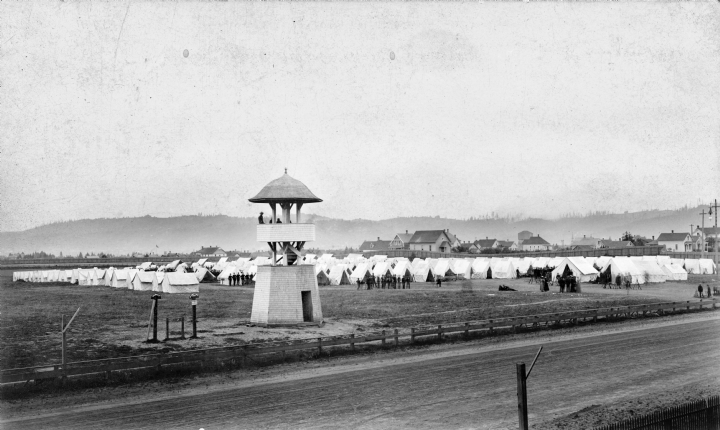

On April 29, 1898, the track was requisitioned as Camp McKinley, an encampment for the federalized Oregon National Guard, which was being sent off to the Philippines to fight in the Spanish-American War. One hundred sixty-one tents were pitched on the grounds until the camp was disbanded around May 19, 1898, when all federal property was removed. Directly across 7th Avenue from the encampment was Ebenezer German Congregational Church, the first congregation established by the Volga Germans in Portland.

Emma Schwabenland Haynes recalls the following story about the camp:

Emma Schwabenland Haynes recalls the following story about the camp:

Mother possessed a plush-covered Memory Book in which her friends wrote dedicatory rhymes of various kinds. One the pages contains the couplet, "Tis war for me. Peace be with thee." and is signed by one of the boys stationed at the Camp McKinley, as the hurriedly constructed barrack inside the racetrack was called during the Spanish-American war of 1898.

Camp McKinley was located inside the Irvington Race Track during the Spanish American War. Circa 1898-99. The Ebenezer German Congregational Church (established 1892) is the large building shown behind and closest to the tents. Digital image used with the permission of the Oregon Historical Society Research Library (Image bb006844).

In 1905, Elizabeth sued the Multnomah Fair Association, claiming the lease terms were violated. Representing Elizabeth was Captain E. W. Spencer, Manager of the Irving Real Estate Company, who also served as her attorney. According to a July 21, 1905 article published in The Oregonian, it seems the dispute focused on whether Elizabeth's nephew, W. S. Dixon, or the MFA would control the betting ring at the track. Years earlier, Dixon had been given the ownership of the betting operation as a condition of the lease assignment to the MFA. Captain Spencer, acting on behalf of Elizabeth Ryan, had consented to the assignment of the lease based on this condition. Dixon controlled the betting ring for two years but had been refused further control by the MFA, who was pressured to allow bookmaking by the locals who viewed Dixon as an outsider. Dixon claimed he had the right to control the betting for two more years.

There was an extensive legal battle, but eventually, Elizabeth regained control of the land. She ultimately divorced Ryan, claiming that he was an abusive drunkard. Later, the racetrack property was laid out in lots. A 1908 prospectus brochure described part of the former racetrack now being developed as "Prospect Park," an area between Knott, Siskiyou, 7th and 14th, and the highest point in Irvington. This area overlooked Holladay Park, the current location of Lloyd Center. The residential area had asphalt streets, cement walks, sewer, water, and gas. In 1912, Augustana Lutheran Church built its parsonage on land that had been part of the race track.

According to the Irvington Historic District Nomination Form, the race track was demolished in 1907. In 1914, 16.26 acres of the former racetrack were dedicated as Irving Park, which must have been a privately owned park then.

There was an extensive legal battle, but eventually, Elizabeth regained control of the land. She ultimately divorced Ryan, claiming that he was an abusive drunkard. Later, the racetrack property was laid out in lots. A 1908 prospectus brochure described part of the former racetrack now being developed as "Prospect Park," an area between Knott, Siskiyou, 7th and 14th, and the highest point in Irvington. This area overlooked Holladay Park, the current location of Lloyd Center. The residential area had asphalt streets, cement walks, sewer, water, and gas. In 1912, Augustana Lutheran Church built its parsonage on land that had been part of the race track.

According to the Irvington Historic District Nomination Form, the race track was demolished in 1907. In 1914, 16.26 acres of the former racetrack were dedicated as Irving Park, which must have been a privately owned park then.

In 1919, the Portland City Council approved a program to acquire land that would be used to create new city parks in areas of the city that had none. At that time, the Albina district did not have a public park. As early as 1904, in John Charles Olmsted's plan for Portland, the area was considered a source of open space and a potential public park.

In December 1919, the City Council approved the purchase of the Irvington racetrack parcel (approximately 15 acres), which at that time was controlled by S. C. Spencer, who may have been acting on behalf of Elizabeth Irving. Mr. Spencer had initially offered the property for $60,000 against an initial assessment by the City of $15,000. According to the February 13, 1920 edition of The Oregonian, the City later assessed the land at $44,000.

After the City Council approved purchasing the Spencer tract, a controversy surrounding another parcel of land in Albina, known as the Dutard tract, made local headlines for several months. The controversy indirectly brought attention to the Volga Germans living in the area.

At the May 5, 1920, City Council meeting, a group of Albina residents led by former City Commissioner Dan Kellaher appeared and urged the purchase of the Dutard tract (owned by H. Dutard) as the neighborhood's city park. Mr. Kellaher objected to the selection of the Spencer tract by Park Superintendent Keyser, or as he said, any other "Kaiser."

"Confine your insults to those present," said Mayor George Baker. "I object to the inferences made against a man who is not here to defend himself. Mr. Keyser is 100 percent American, and it would be wise for you to follow the subject matter in this case rather than make veiled insinuations which will avail you nothing, concluded the Mayor."

Undaunted, Mr. Kellaher and Rev. John Dawson of the Episcopal Church of the Good Shepherd again appeared before the City Council at their June 9, 1920 meeting. They demanded to know if there were plans to purchase the nearby Dutard tract in addition to the Spencer tract.

Rev. Dawson, whose church was several blocks from the Dutard tract, said of the Spencer tract: "This tract is not satisfactory to the children of Albina."

Rev. Dawson explained his position: "The children will not associate with the children who use the Spencer tract. Those children, although entitled to playground facilities, are Russian, and the section in which the Spencer tract is located is known as St. Petersburg." [emphasis added to highlight Rev. Dawson's reference to the Volga Germans who were often seen by others simply as "Russians"]

Commission Sylvester Charles Pier, who was in charge of the Parks Bureau then, stated: "I will not recommend the purchase of the Dutard tract. To members of the council, I wish to state that this matter came before you, and it was by unanimous vote of the council that the Spencer tract was purchased, and the Dutard tract was passed by as almost worthless as a playground."

Mayor Baker went on to say that the Spencer tract had been purchased because of the larger size, which would provide better facilities for the district's children.

Rev. Dawson recalled that several hundred children had been gathered at the Dutard tract when the City Council members stopped on a park inspection trip.

"I was surprised to see all those children there that morning," explained Rev. Dawson.

"You don't know the abilities of Mr. Kellaher," said Mayor Baker.

"Just one of your old political tricks," responded Mr. Kellaher.

"No one knows the game better than you, Dan," confessed the Mayor.

"I've been honest in this matter, George, you know that," asserted Mr. Kellaher.

"Yes, I believe you have for once in your life, Dan," agreed the Mayor.

Mayor Baker then referred the matter to the Commissioner of Finance to see if the Dutard tract could be purchased as a good investment for the City.

Mr. Kellaher asked that he and Rev. Dawson be kept informed if the City Council would consider the matter again.

Mayor Baker replied, "Yes, but this council doesn't want a packed meeting. You two gentlemen are sufficient."

"We have no traveling show," responded Mr. Kellaher.

"What's the matter, did it break up?" concluded the Mayor.

A third reading of an ordinance to purchase the Dutard tract was presented to the City Council in October 1920. Several Commissioners (including Commissioners Pier and Bigelow) voted against the purchase of the small tract for $29,240, but the ordinance was approved by a majority of the council.

In December 1920, the City Council gave final approval to purchase the Dutard tract, and the parcel was named Dawson Park in honor of Rev. Dawson.

Despite Rev. Dawson's concerns about the Russian children, many likely enjoyed playing at Dawson Park.

In December 1919, the City Council approved the purchase of the Irvington racetrack parcel (approximately 15 acres), which at that time was controlled by S. C. Spencer, who may have been acting on behalf of Elizabeth Irving. Mr. Spencer had initially offered the property for $60,000 against an initial assessment by the City of $15,000. According to the February 13, 1920 edition of The Oregonian, the City later assessed the land at $44,000.

After the City Council approved purchasing the Spencer tract, a controversy surrounding another parcel of land in Albina, known as the Dutard tract, made local headlines for several months. The controversy indirectly brought attention to the Volga Germans living in the area.

At the May 5, 1920, City Council meeting, a group of Albina residents led by former City Commissioner Dan Kellaher appeared and urged the purchase of the Dutard tract (owned by H. Dutard) as the neighborhood's city park. Mr. Kellaher objected to the selection of the Spencer tract by Park Superintendent Keyser, or as he said, any other "Kaiser."

"Confine your insults to those present," said Mayor George Baker. "I object to the inferences made against a man who is not here to defend himself. Mr. Keyser is 100 percent American, and it would be wise for you to follow the subject matter in this case rather than make veiled insinuations which will avail you nothing, concluded the Mayor."

Undaunted, Mr. Kellaher and Rev. John Dawson of the Episcopal Church of the Good Shepherd again appeared before the City Council at their June 9, 1920 meeting. They demanded to know if there were plans to purchase the nearby Dutard tract in addition to the Spencer tract.

Rev. Dawson, whose church was several blocks from the Dutard tract, said of the Spencer tract: "This tract is not satisfactory to the children of Albina."

Rev. Dawson explained his position: "The children will not associate with the children who use the Spencer tract. Those children, although entitled to playground facilities, are Russian, and the section in which the Spencer tract is located is known as St. Petersburg." [emphasis added to highlight Rev. Dawson's reference to the Volga Germans who were often seen by others simply as "Russians"]

Commission Sylvester Charles Pier, who was in charge of the Parks Bureau then, stated: "I will not recommend the purchase of the Dutard tract. To members of the council, I wish to state that this matter came before you, and it was by unanimous vote of the council that the Spencer tract was purchased, and the Dutard tract was passed by as almost worthless as a playground."

Mayor Baker went on to say that the Spencer tract had been purchased because of the larger size, which would provide better facilities for the district's children.

Rev. Dawson recalled that several hundred children had been gathered at the Dutard tract when the City Council members stopped on a park inspection trip.

"I was surprised to see all those children there that morning," explained Rev. Dawson.

"You don't know the abilities of Mr. Kellaher," said Mayor Baker.

"Just one of your old political tricks," responded Mr. Kellaher.

"No one knows the game better than you, Dan," confessed the Mayor.

"I've been honest in this matter, George, you know that," asserted Mr. Kellaher.

"Yes, I believe you have for once in your life, Dan," agreed the Mayor.

Mayor Baker then referred the matter to the Commissioner of Finance to see if the Dutard tract could be purchased as a good investment for the City.

Mr. Kellaher asked that he and Rev. Dawson be kept informed if the City Council would consider the matter again.

Mayor Baker replied, "Yes, but this council doesn't want a packed meeting. You two gentlemen are sufficient."

"We have no traveling show," responded Mr. Kellaher.

"What's the matter, did it break up?" concluded the Mayor.

A third reading of an ordinance to purchase the Dutard tract was presented to the City Council in October 1920. Several Commissioners (including Commissioners Pier and Bigelow) voted against the purchase of the small tract for $29,240, but the ordinance was approved by a majority of the council.

In December 1920, the City Council gave final approval to purchase the Dutard tract, and the parcel was named Dawson Park in honor of Rev. Dawson.

Despite Rev. Dawson's concerns about the Russian children, many likely enjoyed playing at Dawson Park.

Sources

Haynes, Emma S. My Mother's People. N.p.: n.p., 1959. Print.

"Irving Park." Portland Parks and Recreation. City of Portland, n.d. Web. 06 Mar. 2013. http://www.portlandonline.com/parks/finder/index.cfm?PropertyID=195&action=ViewPark

Roos, Roy. "Irvington Neighborhood, Portland." Oregon Encyclopedia, Portland State University, n.d. Web. 06 March 2013.

"History of the Irvington Neighborhood." Irvington Community Association. n.p., n.d. Web. 06 Mar. 2013. http://www.irvingtonpdx.com/about/history.html

Oregon Parks & Recreation. "Irvington Historic District Nomination." Web. 06 March 2013. http://heritagedata.prd.state.or.us/historic/index.cfm?do=main.loadFile&load=NR_Noms/10000850.pdf

"Spencer Says No." The Oregonian [Portland] 21 July 1905: p. 14. Newsbank. Web. 06 March 2013.

"Many Go To Races." The Morning Oregonian [Portland]. Newsbank Web. 5 July 1907. Page 1o.

"22 Sites For Parks Offered To City Steps to Purchase Three Authorized by Council." The Oregonian [Portland] 10 December 1919: p. X. Newsbank. Web. 06 March 2013.

"Dutard Site Advocated." The Oregonian [Portland] 06 May 1920: p. X. Newsbank. Web. 06 March 2013.

"Dutard Tract Again Up To City Council." The Oregonian [Portland] 10 June 1920: p. X. Newsbank. Web. 06 March 2013.

"City Acts to Get Park. Dutard Tract Ordinance Passed to 3rd Reading." The Oregonian [Portland] 07 October 1920: p. X. Newsbank. Web. 06 March 2013.

"Dutard Tract Approved. City Council Votes Unanimously to Buy Albina Playground." The Oregonian [Portland] 31 December 1920: p. X. Newsbank. Web. 06 March 2013.

1901 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Portland, Multnomah County, Oregon. Sheet 234. Accessed on the Library of Congress website on 5 November 2022.

"Irving Park." Portland Parks and Recreation. City of Portland, n.d. Web. 06 Mar. 2013. http://www.portlandonline.com/parks/finder/index.cfm?PropertyID=195&action=ViewPark

Roos, Roy. "Irvington Neighborhood, Portland." Oregon Encyclopedia, Portland State University, n.d. Web. 06 March 2013.

"History of the Irvington Neighborhood." Irvington Community Association. n.p., n.d. Web. 06 Mar. 2013. http://www.irvingtonpdx.com/about/history.html

Oregon Parks & Recreation. "Irvington Historic District Nomination." Web. 06 March 2013. http://heritagedata.prd.state.or.us/historic/index.cfm?do=main.loadFile&load=NR_Noms/10000850.pdf

"Spencer Says No." The Oregonian [Portland] 21 July 1905: p. 14. Newsbank. Web. 06 March 2013.

"Many Go To Races." The Morning Oregonian [Portland]. Newsbank Web. 5 July 1907. Page 1o.

"22 Sites For Parks Offered To City Steps to Purchase Three Authorized by Council." The Oregonian [Portland] 10 December 1919: p. X. Newsbank. Web. 06 March 2013.

"Dutard Site Advocated." The Oregonian [Portland] 06 May 1920: p. X. Newsbank. Web. 06 March 2013.

"Dutard Tract Again Up To City Council." The Oregonian [Portland] 10 June 1920: p. X. Newsbank. Web. 06 March 2013.

"City Acts to Get Park. Dutard Tract Ordinance Passed to 3rd Reading." The Oregonian [Portland] 07 October 1920: p. X. Newsbank. Web. 06 March 2013.

"Dutard Tract Approved. City Council Votes Unanimously to Buy Albina Playground." The Oregonian [Portland] 31 December 1920: p. X. Newsbank. Web. 06 March 2013.

1901 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Portland, Multnomah County, Oregon. Sheet 234. Accessed on the Library of Congress website on 5 November 2022.

Last updated October 25, 2023