People > Our People > Johannes and Anna Margaretha Schmidt

Johannes and Anna Margaretha Schmidt

I did not have the privilege of knowing my maternal grandparents, John and Anna Schmidt. Both died before my birth in 1956. I wanted to learn more about them and began studying the fragments of their lives gleaned from old documents and family stories. It's certainly not the same as spending time with them when they were living, but it has given me a sense of who they were and their lives.

Steve Schreiber

Steve Schreiber

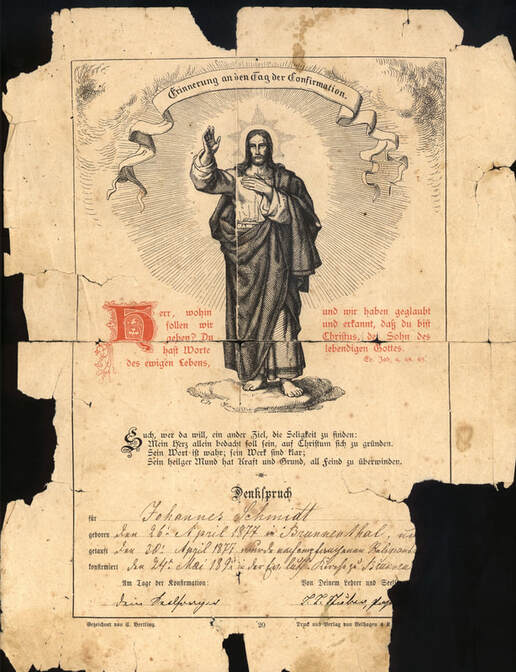

Johannes Schmidt was born April 26, 1877, in the colony of Brunnental, Russia, the son of Johannes Schmidt (born 1845 in Dietel, Russia) and Catharina Margaretha Molko (born 1848 in Warenburg, Russia). Johannes was baptized on April 30, 1877, in the Brunnental church, where he would also be confirmed 15 years later in 1892.

Anna Margaretha Hartung was born on December 31, 1877 in Brunnental. She was confirmed in 1893. Her parents were Johann Jacob Hartung (born 1840 in Frank, Russia) and Catharina Elisabeth Zitzmann (born 1842 in Frank).

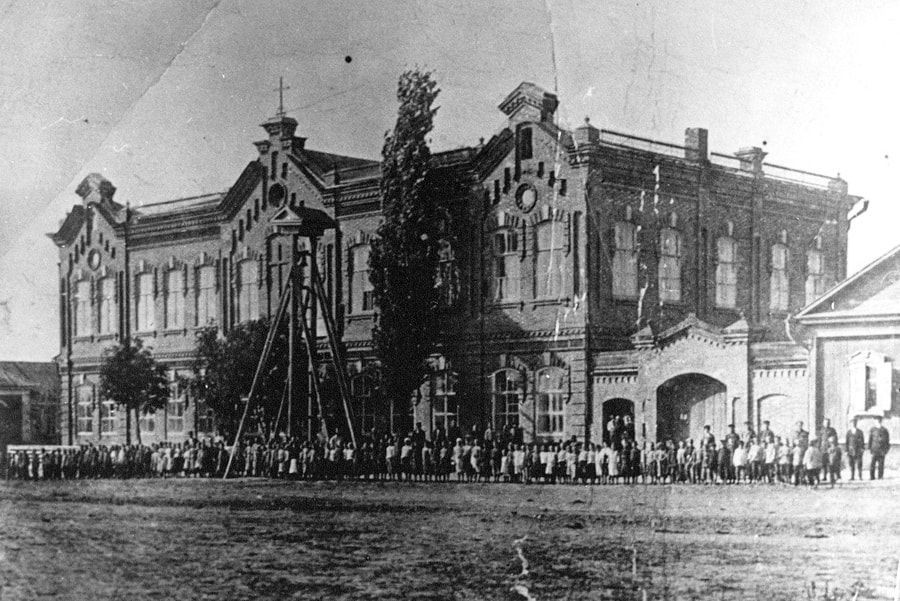

Johannes and Anna Margaretha were married on January 19, 1898, in Brunnental. The wooden church in the colony was not heated during the winter months due to the cost and risk of fire. As a result, Johannes and Anna were likely married in the school, which also served as the Gebethaus (house of prayer) during the winter months.

Johannes and Anna Margaretha were married on January 19, 1898, in Brunnental. The wooden church in the colony was not heated during the winter months due to the cost and risk of fire. As a result, Johannes and Anna were likely married in the school, which also served as the Gebethaus (house of prayer) during the winter months.

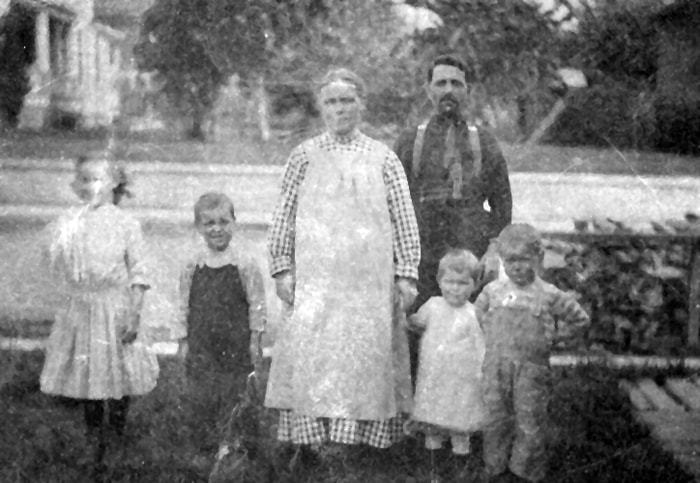

Johannes and Anna Margaretha's first child, Johannes, was born on March 31, 1898. Five more children were born in Brunnental. Maria was born on November 4, 1899. Heinrich was born on December 23, 1901. A daughter, Anna Marie (known as Marie), was born August 12, 1903. Another daughter with the same name, but known as Anna, was born on February 26, 1905. The last child born in Russia was a daughter named Amalia (known as Molly), who arrived on October 9, 1906.

Johannes and Anna Margaretha suffered a series of tragedies in 1907. Three of their children, Maria, Heinrich, and Amalia, died, possibly from a cholera epidemic that swept through the Volga basin that year.

Life was getting progressively worse for the Volga Germans. The privileges granted by Catherine the Great had been stripped away. The Russian government was in danger of collapse after the disastrous Russo-Japanese War. Revolutionaries had already attempted to overthrow the government in 1905. Many Brunnentalers (and Volga Germans in general) emigrated from Russia based on positive reports from family and friends who had migrated to Amerika. Sometime during the summer of 1907, Johannes and Anna Margaretha decided to leave their homeland for a new life in the United States. Johannes' brother, Philip Heinrich (known as "Philip"), had already emigrated and was living in Portland, Oregon. His sister, Maria Catharina, departed for America in 1907. Anna Margaretha's brother Jacob arrived in the USA in 1899, and her brother George came in 1907. This was chain migration in action.

Johannes and Anna Margaretha suffered a series of tragedies in 1907. Three of their children, Maria, Heinrich, and Amalia, died, possibly from a cholera epidemic that swept through the Volga basin that year.

Life was getting progressively worse for the Volga Germans. The privileges granted by Catherine the Great had been stripped away. The Russian government was in danger of collapse after the disastrous Russo-Japanese War. Revolutionaries had already attempted to overthrow the government in 1905. Many Brunnentalers (and Volga Germans in general) emigrated from Russia based on positive reports from family and friends who had migrated to Amerika. Sometime during the summer of 1907, Johannes and Anna Margaretha decided to leave their homeland for a new life in the United States. Johannes' brother, Philip Heinrich (known as "Philip"), had already emigrated and was living in Portland, Oregon. His sister, Maria Catharina, departed for America in 1907. Anna Margaretha's brother Jacob arrived in the USA in 1899, and her brother George came in 1907. This was chain migration in action.

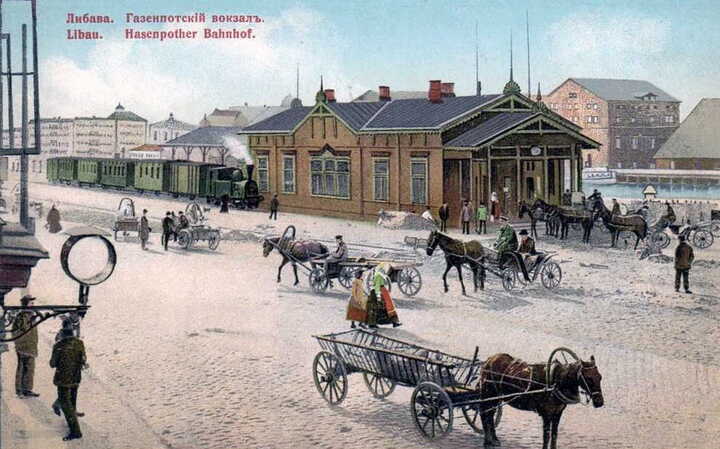

It was a sad day when the Schmidt family departed from Brunnental in the fall of 1907. They knew that they would probably never see their family and friends again. Once they reached the city of Saratov, the Schmidts traveled by train on the Libau-Romnyer railroad to the port city of Libau, Russia (now Liepaja, Latvia). Only a few months later, a fellow named Gottfried Schreiber from Norka, Russia, passed through this same station and port on his way to America. Remember Gottfried. We will come back to him later in this story.

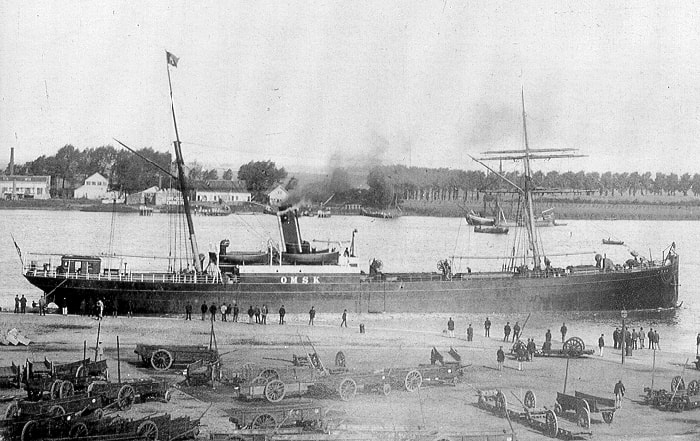

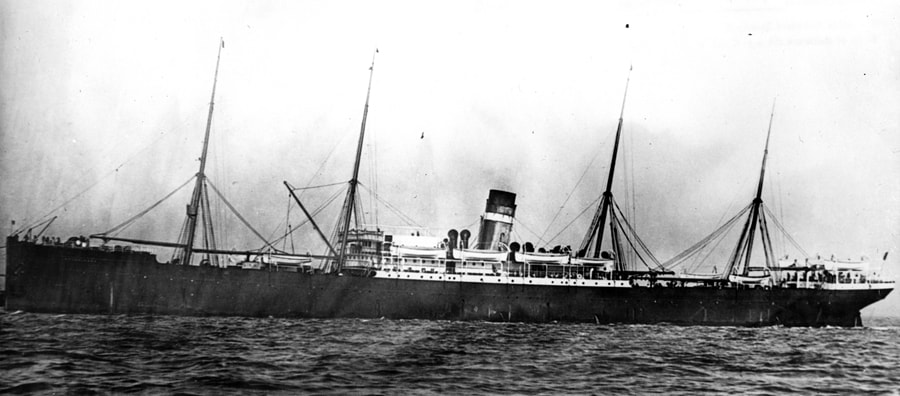

In Libau, the Schmidt's boarded the cargo steamship Omsk, which was bound for Kingston upon Hull, England, a large seaport on the eastern coastline at that time. The Omsk was not explicitly built for passengers but could carry up to 24 people in addition to cargo. After disembarking at Hull, the family boarded an emigrant train that traveled west across the English Midlands to Liverpool. Here, the Schmidt family boarded the steamship Kensington, bound for Québec, Canada.

The Kensington, part of the Dominion Line, sailed from Liverpool on October 24, 1907, under the command of Captain William Roberts. After a sea voyage of 2,613 miles, the Kensington arrived at Grosse Isle near Québec at 4:00 a.m. on November 3, 1907.

The ship's passenger list shows the Schmidt family members included Johannes (age 31), Anna (age 29), Johannes (age 8), Marie (age 4), Anna (age 2) and Johannes's mother, Margaretha (age 58).

Johannes and his family were traveling with a group from Brunnental who were all bound for Portland. The group members were listed together with consecutive Railway Order Numbers.

There were 1,007 passengers aboard the ship, and 881 traveled in steerage class. The official carrying capacity of the Kensington was 1,503 passengers. Upon arrival, the ship anchored at Grosse Isle, located in the St. Lawrence River northeast (downstream) of Québec. Grosse Isle is sometimes referred to as the Canadian Ellis Island. At 6:25 in the morning, two medical examiners began a health inspection of each passenger on the ship's upper deck. Three people from the ship were held in quarantine at Gross Isle because of Scarlet Fever. Fortunately, the Schmidt family was not among those held, and the inspection of passengers concluded at 9:00 a.m. After the inspection, the medical examiners signed a certificate that the ship was "clean. The Kensington proceeded upriver to the dock at Point Lévis on the south shore of the St. Lawrence River opposite Québec City.

The ship's passenger list shows the Schmidt family members included Johannes (age 31), Anna (age 29), Johannes (age 8), Marie (age 4), Anna (age 2) and Johannes's mother, Margaretha (age 58).

Johannes and his family were traveling with a group from Brunnental who were all bound for Portland. The group members were listed together with consecutive Railway Order Numbers.

- Anna Schlothauer (age 18)

- Adam (age 25) and Anna (age 19) Hergert and their son Heinrich (age 1)

- Elias (age 29) and Marie (age 27) Hergert. After his brother Jacob's death, Elias Hergert became an ordained minister and pastor of Portland's St. Pauls Evangelical and Reformed Church.

- Konrad (age 37) and Katharina (age 35) Linker and their children: Konrad (age 7), Heinrich (age 4), Maria (age 3) and Anna (age 1).

There were 1,007 passengers aboard the ship, and 881 traveled in steerage class. The official carrying capacity of the Kensington was 1,503 passengers. Upon arrival, the ship anchored at Grosse Isle, located in the St. Lawrence River northeast (downstream) of Québec. Grosse Isle is sometimes referred to as the Canadian Ellis Island. At 6:25 in the morning, two medical examiners began a health inspection of each passenger on the ship's upper deck. Three people from the ship were held in quarantine at Gross Isle because of Scarlet Fever. Fortunately, the Schmidt family was not among those held, and the inspection of passengers concluded at 9:00 a.m. After the inspection, the medical examiners signed a certificate that the ship was "clean. The Kensington proceeded upriver to the dock at Point Lévis on the south shore of the St. Lawrence River opposite Québec City.

The passengers disembarked from the Kensington and boarded a special train on the main branch of the Grand Trunk Railway, which departed at 2:00 in the afternoon. The Schmidt's traveled under Railway Order Number 26413. Their passage had been paid for by Johannes's brother, Heinrich Philip Schmidt, who had arrived in the United States in 1900.

From Point Lévis, the special train traveled southwest on the Grand Trunk main line, crossing to the north side of the St. Lawrence River at Montreal. The train continued to Toronto and Detroit, where the Schmidt's are recorded as entering the United States on November 4th. The family had $34.00 when they entered the country. The train likely continued to Chicago, the terminus of the Grand Trunk Railway. In Chicago, the Schmidts and the other families from Brunnental probably changed to a Northern Pacific train to continue their journey to Portland, Oregon. When they arrived at Portland's Union Station, the entire Brunnental party was likely met by family and friends who were expecting them.

The Schmidt family settled in the Volga German enclave located in the Albina area. The 1909 Portland City Directory shows that John was working as a laborer for Elwood Wiles, a contractor who built sidewalks and curbs across Portland's Eastside. John and his family resided at 868 E 6th N. (now near 4036 NE 6th Avenue).

Johannes and Anna Margaretha became members of St. Pauls Evangelical and Reformed Church upon their arrival in Portland. They were instrumental in the church's foundation and remained part of this congregation until their deaths. The church's first pastor was Rev. Jacob Hergert, also from Brunnental. Jacob's brother, Elias, traveled from Brunnental to Portland with the Schmidts and became church pastor in 1925 after Jacob's death. In John's obituary, Rev. Elias Hergert writes that John was an excellent Sunday School teacher and served as a Church Elder for many years.

Less than a year after their arrival in Portland, Johannes (now known as "John") and Anna Margaretha (now known as "Anna" or "Annie") celebrated the birth of their first child born in America, Jacob, on April 4, 1908. Another son, George, was born on March 26, 1910.

According to the 1910 U.S. Census, the Schmidt family lived at 912 Grand Avenue North (now 4226 NE Grand Ave.). Johannes worked as a laborer installing part of Portland's first sewer system. Anna was working as a "wash woman" for private clients. The 1910 City Directory, probably compiled before the 1910 census, shows that John worked on Oregon Railway and Navigation ships in Albina.

A son, Alexander, was born on December 3, 1911.

From Point Lévis, the special train traveled southwest on the Grand Trunk main line, crossing to the north side of the St. Lawrence River at Montreal. The train continued to Toronto and Detroit, where the Schmidt's are recorded as entering the United States on November 4th. The family had $34.00 when they entered the country. The train likely continued to Chicago, the terminus of the Grand Trunk Railway. In Chicago, the Schmidts and the other families from Brunnental probably changed to a Northern Pacific train to continue their journey to Portland, Oregon. When they arrived at Portland's Union Station, the entire Brunnental party was likely met by family and friends who were expecting them.

The Schmidt family settled in the Volga German enclave located in the Albina area. The 1909 Portland City Directory shows that John was working as a laborer for Elwood Wiles, a contractor who built sidewalks and curbs across Portland's Eastside. John and his family resided at 868 E 6th N. (now near 4036 NE 6th Avenue).

Johannes and Anna Margaretha became members of St. Pauls Evangelical and Reformed Church upon their arrival in Portland. They were instrumental in the church's foundation and remained part of this congregation until their deaths. The church's first pastor was Rev. Jacob Hergert, also from Brunnental. Jacob's brother, Elias, traveled from Brunnental to Portland with the Schmidts and became church pastor in 1925 after Jacob's death. In John's obituary, Rev. Elias Hergert writes that John was an excellent Sunday School teacher and served as a Church Elder for many years.

Less than a year after their arrival in Portland, Johannes (now known as "John") and Anna Margaretha (now known as "Anna" or "Annie") celebrated the birth of their first child born in America, Jacob, on April 4, 1908. Another son, George, was born on March 26, 1910.

According to the 1910 U.S. Census, the Schmidt family lived at 912 Grand Avenue North (now 4226 NE Grand Ave.). Johannes worked as a laborer installing part of Portland's first sewer system. Anna was working as a "wash woman" for private clients. The 1910 City Directory, probably compiled before the 1910 census, shows that John worked on Oregon Railway and Navigation ships in Albina.

A son, Alexander, was born on December 3, 1911.

Tragedy struck on April 5, 1911. Johannes's brother, Philip, was killed when a sewer trench he was working in collapsed, causing him to suffocate. He left a widowed wife and six children.

Anna gave birth to a baby boy on March 11, 1913. Sadly, he died on the same date.

The Portland City Directory shows that John and Anna lived at 95 Stanton in 1914 (now 931 N Stanton Street). John worked as a railroad car repairman.

John's World War I Registration Card shows that he was a carpenter for the Oregon, Washington, Railway and Navigation Company in the Albina yard. As a result of strong anti-German feelings during the war, Portland school officials advised the Schmidts to anglicize the spelling of their surname to Smith, which they did. At the time, the family lived at 861 Grand Avenue North (now 4027 NE Grand Avenue).

On May 7, 1914, Anna and Johannes celebrated the birth of their son Fredrick. Another daughter, Lydia, became part of the family on March 6, 1916. Two more children would become part of this large family: Heinrich (Henry) was born on February 13, 1918, and Esther Grace was born on March 14, 1920.

The 1920 U.S. Census shows that John, Anna and their family continued to live at 861 Grand Avenue North. John continued to work as a carpenter at the shipyard in Portland.

Family members recall that Anna believed certain people had a supernatural power to heal and to place a hex (curse) on others. Superstitions were common amongst the Volga Germans despite their beliefs in Christianity. Both belief systems were held simultaneously.

Anna gave birth to a baby boy on March 11, 1913. Sadly, he died on the same date.

The Portland City Directory shows that John and Anna lived at 95 Stanton in 1914 (now 931 N Stanton Street). John worked as a railroad car repairman.

John's World War I Registration Card shows that he was a carpenter for the Oregon, Washington, Railway and Navigation Company in the Albina yard. As a result of strong anti-German feelings during the war, Portland school officials advised the Schmidts to anglicize the spelling of their surname to Smith, which they did. At the time, the family lived at 861 Grand Avenue North (now 4027 NE Grand Avenue).

On May 7, 1914, Anna and Johannes celebrated the birth of their son Fredrick. Another daughter, Lydia, became part of the family on March 6, 1916. Two more children would become part of this large family: Heinrich (Henry) was born on February 13, 1918, and Esther Grace was born on March 14, 1920.

The 1920 U.S. Census shows that John, Anna and their family continued to live at 861 Grand Avenue North. John continued to work as a carpenter at the shipyard in Portland.

Family members recall that Anna believed certain people had a supernatural power to heal and to place a hex (curse) on others. Superstitions were common amongst the Volga Germans despite their beliefs in Christianity. Both belief systems were held simultaneously.

Despite their limited financial resources, John and Anna contributed to the Volga Relief Society, founded in Portland by George Repp and John W. Miller in 1921. Their monetary support to the society was converted to food remittances. They hoped the remittances would help save the lives of families still living in their Volga homeland. The region had been hit by a severe famine partly caused by drought. The Volga Germans were accustomed to periodic droughts, but the Bolshevik Revolution and subsequent Russian Civil War made the situation infinitely worse. The Bolsheviks confiscated seed grain and reserve food supplies, leaving the German colonies in a dire situation. John's widowed mother, Catharina Margaretha, traveled with them to Portland in 1907. She became homesick and returned to Brunnental several times. Her last trip to Russia was about 1911. She likely survived the famine of the 1920s due to the help of John and Anna. She was not as fortunate during the subsequent largely man-made famine, which began in 1932. This catastrophe was known in Ukraine as the Holmodor and, more generally, the Great Famine. Many countries, including the United States, have recognized this engineered famine as an act of genocide.

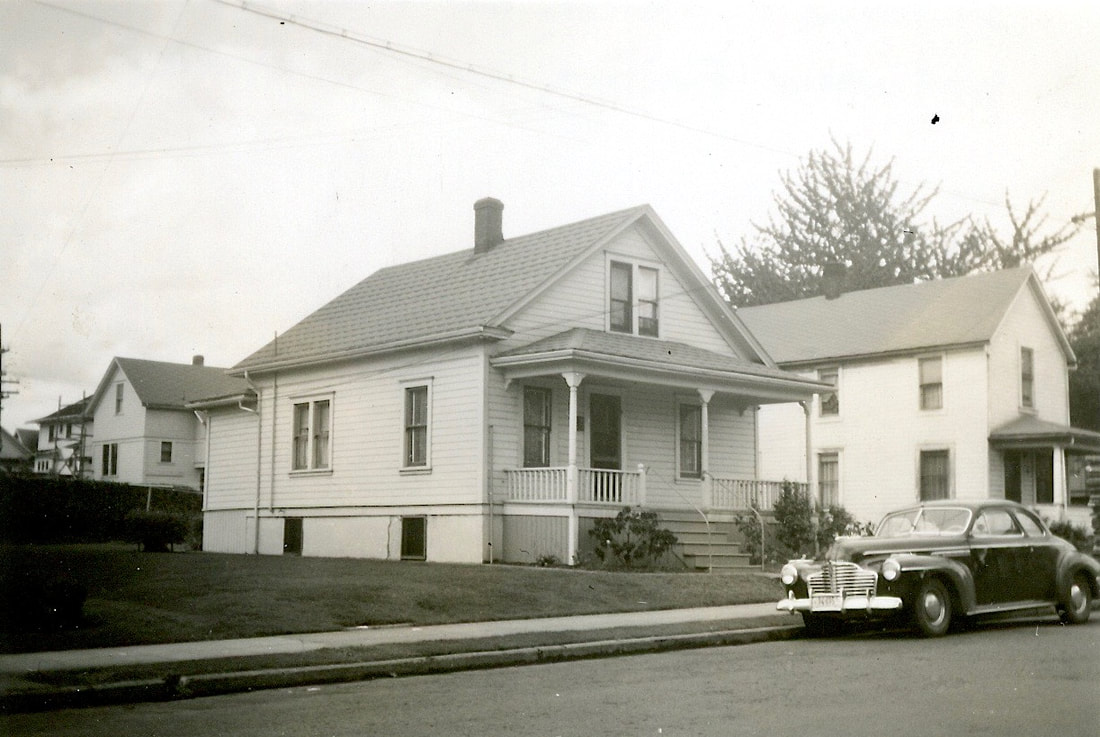

On February 8, 1922, John filed a Declaration of Intention to become a citizen of the United States. This document shows that the family lived at 835 E. 13th Street N. (now 3947 NE 13th Avenue). John continued his work as a carpenter at the time, likely for one of the railroads.

On February 8, 1922, John filed a Declaration of Intention to become a citizen of the United States. This document shows that the family lived at 835 E. 13th Street N. (now 3947 NE 13th Avenue). John continued his work as a carpenter at the time, likely for one of the railroads.

In 1923, Rev. Elias Hergert wrote a poem that mentions many of the people from Brunnental. Within the poem is an excerpt that speaks highly of John:

George and Heinrich Baum, John Schmidt

Each one has a heart;

George Melcher kept in step with them and continued his pleasantries.

In the fall of 1928, John suffered a work-related injury when his hand was damaged by a hammer blow. The injury led to sudden pain in his left arm, likely due to blood poisoning (sepsis), a life-threatening infection that can move rapidly to the heart, kidneys, and lungs. John prophetically told family and friends that he knew his life was in danger. He died on November 1st from acute lobar pneumonia at the age of 51. His dear friend and countryman, Rev. Elias Hergert, presided over his funeral at the St. Paul's church. John was buried later that day at the Rose City Cemetery. I was told by cemetery staff that the section he was buried in was designated for poor people at that time. As his children prospered, they replaced the small stamped concrete marker at his grave with a finer headstone.

Now a widow, Anna had six children living at home. John, Mary, and Jacob were married by this time and living independently. Her older sons, George and Alex, helped raise their younger siblings and provided much-needed financial resources for the family. The 1930 census shows that George was a cabinet maker at a furniture factory (probably Doernbecher). Alex was a spooler at a knitting mill (probably Jantzen). Fred, Lydia, Henry, and Esther are attending school. According to George's daughter, Karen Luna (née Smith), George was recruited by the San Francisco Seals to play professional baseball. Anna did not want him to go because she needed him at home to help with the youngest children. George honored his mother's wish. He stayed home and played locally for Rotary Bread and other company teams. Sometimes, George teamed up with the very talented Jake Hergert, the son of Pastor Elias Hergert.

The 1940 U.S. census shows that Anna, Lydia, Henry, and Esther continued to live in the house on NE 13th. Henry worked at Doernbecher Furniture, and Esther was an inspector at New System Laundry. Like their brother George, Henry and Esther were outstanding athletes and played semi-professional softball. Anna was asked supplemental questions by the census taker. She confirmed that she spoke German as her native language and that German was spoken in the home. She also confirmed that she had no Social Security number, Old-Age Insurance, or Railroad Retirement benefits.

As war swept across Europe in the summer of 1941, Anna may have feared that her German heritage would work against her despite being born in Russia. She filed a Declaration of Intention to become a U.S. citizen on September 15, 1941. Neighborhood grocery store owner Marie Danewolf served as her witness. The United States declared war on Germany in December.

Anna's youngest son, Henry, enlisted in the U.S. Army on October 9, 1942. Henry served as a member of Company C, 21st Armored Infantry Battalion, which was part of the 11th Armored Infantry Division. Henry's company fought in key battles leading to the end of World War II. Tragically, he was killed in Germany on March 6, 1945. The news of Henry's death was devastating to Anna and his siblings. Henry was initially buried at a military cemetery in Belgium. Several years later, Anna requested that his remains be returned to Portland, where he was interred at Rose City Cemetery in 1949.

Earlier in the story, I mentioned a fellow named Gottfried Schreiber. Remember him? He also emigrated from the port of Libau shortly after the Schmidts passed through in 1907. Gottfried married Elizabeth Döring in Portland. The Schreibers lived across NE 13th Street from John and Anna. Gottfried and Elizabeth's son, Frederick, and Johannes and Anna Margaretha's daughter, Esther, married in 1943. Small world. My story begins 13 years later!

In her last years, Anna suffered from diabetes, heart disease, and dementia (probably Alzheimer's). Her children took turns caring for her as her health declined. After a life full of joy and sadness, Anna died at her home on October 16, 1950, at the age of 72. Her funeral service was held at St. Pauls church, and many family members and friends attended. The following scripture from Revelations 14:13 was read at her service by Pastor Bock:

Then I heard a voice from heaven say, “Write this: Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord from now on.”

“Yes,” says the Spirit, “they will rest from their labor, for their deeds will follow them.”

Anna was buried the same day at the Rose City Cemetery near John and their Portland-born children who preceded them in death.

I remember that my mother and her siblings were very close. We spent a lot of time visiting family who mostly lived close by. As a kid, sorting out the connections with all the aunts, uncles, and cousins was a little overwhelming. I now understand what a remarkable support network it was. Together, they survived adversity and thrived in a new homeland.

Although I never met my grandparents, researching their story has allowed me to know and appreciate them.

Now a widow, Anna had six children living at home. John, Mary, and Jacob were married by this time and living independently. Her older sons, George and Alex, helped raise their younger siblings and provided much-needed financial resources for the family. The 1930 census shows that George was a cabinet maker at a furniture factory (probably Doernbecher). Alex was a spooler at a knitting mill (probably Jantzen). Fred, Lydia, Henry, and Esther are attending school. According to George's daughter, Karen Luna (née Smith), George was recruited by the San Francisco Seals to play professional baseball. Anna did not want him to go because she needed him at home to help with the youngest children. George honored his mother's wish. He stayed home and played locally for Rotary Bread and other company teams. Sometimes, George teamed up with the very talented Jake Hergert, the son of Pastor Elias Hergert.

The 1940 U.S. census shows that Anna, Lydia, Henry, and Esther continued to live in the house on NE 13th. Henry worked at Doernbecher Furniture, and Esther was an inspector at New System Laundry. Like their brother George, Henry and Esther were outstanding athletes and played semi-professional softball. Anna was asked supplemental questions by the census taker. She confirmed that she spoke German as her native language and that German was spoken in the home. She also confirmed that she had no Social Security number, Old-Age Insurance, or Railroad Retirement benefits.

As war swept across Europe in the summer of 1941, Anna may have feared that her German heritage would work against her despite being born in Russia. She filed a Declaration of Intention to become a U.S. citizen on September 15, 1941. Neighborhood grocery store owner Marie Danewolf served as her witness. The United States declared war on Germany in December.

Anna's youngest son, Henry, enlisted in the U.S. Army on October 9, 1942. Henry served as a member of Company C, 21st Armored Infantry Battalion, which was part of the 11th Armored Infantry Division. Henry's company fought in key battles leading to the end of World War II. Tragically, he was killed in Germany on March 6, 1945. The news of Henry's death was devastating to Anna and his siblings. Henry was initially buried at a military cemetery in Belgium. Several years later, Anna requested that his remains be returned to Portland, where he was interred at Rose City Cemetery in 1949.

Earlier in the story, I mentioned a fellow named Gottfried Schreiber. Remember him? He also emigrated from the port of Libau shortly after the Schmidts passed through in 1907. Gottfried married Elizabeth Döring in Portland. The Schreibers lived across NE 13th Street from John and Anna. Gottfried and Elizabeth's son, Frederick, and Johannes and Anna Margaretha's daughter, Esther, married in 1943. Small world. My story begins 13 years later!

In her last years, Anna suffered from diabetes, heart disease, and dementia (probably Alzheimer's). Her children took turns caring for her as her health declined. After a life full of joy and sadness, Anna died at her home on October 16, 1950, at the age of 72. Her funeral service was held at St. Pauls church, and many family members and friends attended. The following scripture from Revelations 14:13 was read at her service by Pastor Bock:

Then I heard a voice from heaven say, “Write this: Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord from now on.”

“Yes,” says the Spirit, “they will rest from their labor, for their deeds will follow them.”

Anna was buried the same day at the Rose City Cemetery near John and their Portland-born children who preceded them in death.

I remember that my mother and her siblings were very close. We spent a lot of time visiting family who mostly lived close by. As a kid, sorting out the connections with all the aunts, uncles, and cousins was a little overwhelming. I now understand what a remarkable support network it was. Together, they survived adversity and thrived in a new homeland.

Although I never met my grandparents, researching their story has allowed me to know and appreciate them.

Sources

Written by Steven Schreiber.

Last updated October 26, 2023