People > Our People > Heinrich Schmidt

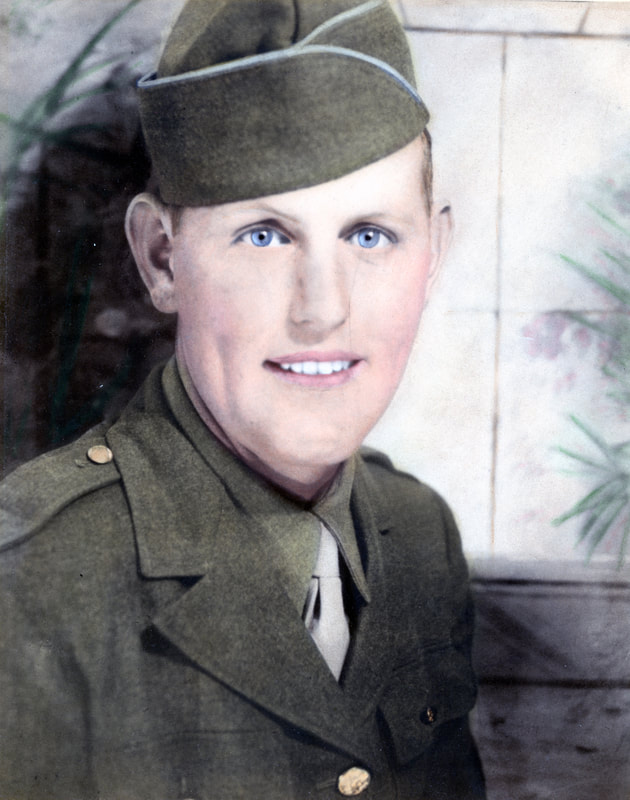

Henry Smith

Written by Steven Henry Schreiber, nephew of Henry Smith

Heinrich Schmidt was born in Portland on February 13, 1918, in the midst of World War I and the Spanish flu pandemic. Heinrich was the 13th of 14 children, although five of his siblings died in childhood before his birth. His parents, Johannes Schmidt and Anna Margaretha Hartung, were descendants of ethnic Germans who were enticed to leave their homeland in the 1760s to become colonists in Russia's lower Volga River region. One of the promises made by the Russian Czarina, Catherine the Great, was that these colonists and their descendants would be exempt from military service forever. This was a powerful incentive for people who survived the Seven Years' War, recognized by many historians as the First World War.

Heinrich's parents and his siblings John and Mary departed from the German colony of Brunnental, Russia, and arrived in Quebec, Canada, aboard the steamship Kensington in November 1907. They immediately traveled by train to Portland, Oregon, to join family members and friends determined to make a new life in America. Volga Germans began migrating to the Americas in 1875, shortly after the promise of military exemption and many other promises were broken by the Russian government.

At the time of Heinrich's birth, anti-German sentiment was strong in the United States. As a result, Portland public school officials advised the Schmidts to change the spelling of the family name to Smith, an Anglicized version of Schmidt. Heinrich was known as Henry or by his nickname of "Heine." German was spoken at home, church, and the Volga German neighborhood. Many Volga German children could not speak English when they began attending public schools.

Heinrich's parents and his siblings John and Mary departed from the German colony of Brunnental, Russia, and arrived in Quebec, Canada, aboard the steamship Kensington in November 1907. They immediately traveled by train to Portland, Oregon, to join family members and friends determined to make a new life in America. Volga Germans began migrating to the Americas in 1875, shortly after the promise of military exemption and many other promises were broken by the Russian government.

At the time of Heinrich's birth, anti-German sentiment was strong in the United States. As a result, Portland public school officials advised the Schmidts to change the spelling of the family name to Smith, an Anglicized version of Schmidt. Heinrich was known as Henry or by his nickname of "Heine." German was spoken at home, church, and the Volga German neighborhood. Many Volga German children could not speak English when they began attending public schools.

Henry's father, John, tragically died of pneumonia in November 1928 at the age of 51. This was a difficult situation for a boy of ten, putting enormous pressure on his mother to take care of the family. All of the children pitched in to help. The older siblings (John, Mary, Jake, George, and Alex) helped raise their younger siblings (Fred, Lydia, Henry, and Esther). Driven by adversity, family ties remained strong over time, and Anna's children took turns caring for her towards the end of her life.

Henry attended the St. Paul's Evangelical and Reformed Church on NE 8th and Failing, a short walk from the family home on NE 13th. He was confirmed on April 9, 1933, by Pastor Elias Hergert.

Henry often walked to Sabin Elementary School with his sisters Esther and Lydia. He continued his education at Benson Polytechnic High School, where he learned trade skills that helped him land a job building furniture at Doernbecher Manufacturing Company.

Henry was remembered as a very bright and outgoing person. He was an outstanding baseball and softball player. Many thought he had the potential to play professional baseball. His brother George and sister Esther were standout players for local semi-professional teams.

Henry attended the St. Paul's Evangelical and Reformed Church on NE 8th and Failing, a short walk from the family home on NE 13th. He was confirmed on April 9, 1933, by Pastor Elias Hergert.

Henry often walked to Sabin Elementary School with his sisters Esther and Lydia. He continued his education at Benson Polytechnic High School, where he learned trade skills that helped him land a job building furniture at Doernbecher Manufacturing Company.

Henry was remembered as a very bright and outgoing person. He was an outstanding baseball and softball player. Many thought he had the potential to play professional baseball. His brother George and sister Esther were standout players for local semi-professional teams.

The outbreak of World War II cut short Henry's dream of playing professional baseball. Henry worked for the Oregon Shipbuilding Corporation as a ship fitter to support the war effort. Founded by Henry J. Kaiser, the Kaiser Shipyards launched over 600 Liberty and Victory ships between 1941 and 1945.

Henry enlisted in the U.S. Army on October 9, 1942. Despite the long aversion to war, Henry was among many young descendants of Volga Germans who volunteered to serve in the U.S. armed forces. They felt strongly that American ideals were worth fighting for. It was their choice, not one imposed upon them.

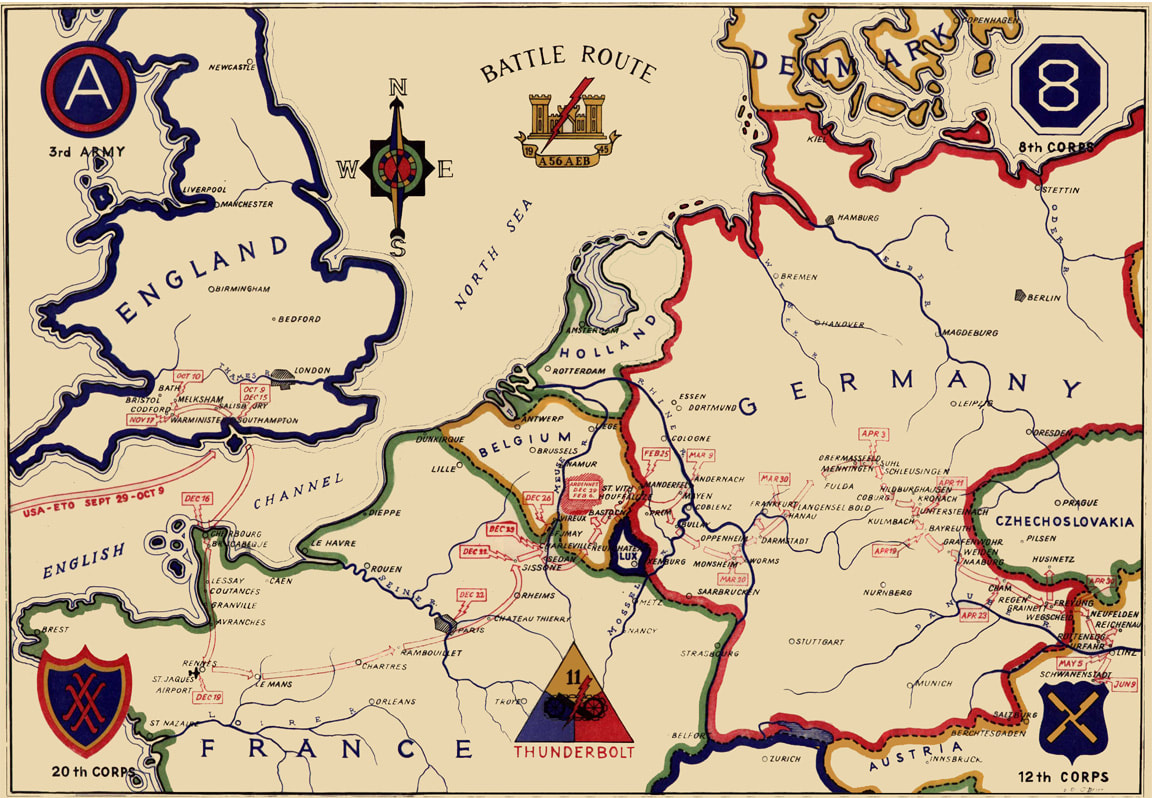

Henry was assigned to Company C, 21st Armored Infantry Battalion, part of the 11th Armored Division. Company C was initially sent to Camp Polk, Louisiana, where they later participated in the Louisiana Maneuvers. They later transferred to Camp Barkeley, Texas (on September 5, 1943) to continue their training exercises. On February 11, 1944, the 11th Division transferred to Camp Cooke, California, to participate in desert training as a part of the California Maneuvers.

After the successful D-Day Invasion at Normandy, the 11th Division staged for deployment to Europe at Camp Kilmer, New Jersey, from mid-September 1944 until their departure by steamship from New York on September 29, 1944. Henry arrived in England on October 11, 1944, and prepared for live combat with two months of training on the Salisbury Plain near Bath. He undoubtedly found time to visit nearby Stonehenge and the magnificent Salisbury Cathedral. Henry was not the first family member to visit England. He had surely heard stories from his parents about their travels to America in 1907. The Schmidt's departed from the European mainland at Libau and arrived by steamship at Kingston upon Hull. They traveled across the English Midlands by train from Hull to Liverpool, where they boarded the passenger ship Kensington, bound for Quebec.

Henry enlisted in the U.S. Army on October 9, 1942. Despite the long aversion to war, Henry was among many young descendants of Volga Germans who volunteered to serve in the U.S. armed forces. They felt strongly that American ideals were worth fighting for. It was their choice, not one imposed upon them.

Henry was assigned to Company C, 21st Armored Infantry Battalion, part of the 11th Armored Division. Company C was initially sent to Camp Polk, Louisiana, where they later participated in the Louisiana Maneuvers. They later transferred to Camp Barkeley, Texas (on September 5, 1943) to continue their training exercises. On February 11, 1944, the 11th Division transferred to Camp Cooke, California, to participate in desert training as a part of the California Maneuvers.

After the successful D-Day Invasion at Normandy, the 11th Division staged for deployment to Europe at Camp Kilmer, New Jersey, from mid-September 1944 until their departure by steamship from New York on September 29, 1944. Henry arrived in England on October 11, 1944, and prepared for live combat with two months of training on the Salisbury Plain near Bath. He undoubtedly found time to visit nearby Stonehenge and the magnificent Salisbury Cathedral. Henry was not the first family member to visit England. He had surely heard stories from his parents about their travels to America in 1907. The Schmidt's departed from the European mainland at Libau and arrived by steamship at Kingston upon Hull. They traveled across the English Midlands by train from Hull to Liverpool, where they boarded the passenger ship Kensington, bound for Quebec.

Over two years, Henry had proven himself a very competent soldier and leader. His commanding General recommended him for promotion, and he quickly rose from private to staff sergeant. As a non-commissioned officer, he was responsible for a squad or a platoon.

The 11th Armored Division, known as the "Thunderbolts," landed in Normandy, France on December 16, 1944. Their first assignment was to contain the enemy in the Lorient Pocket. However, the German Von Rundstedt offensive resulted in a forced march to the Meuse and a focus on defending a 30-mile sector from Givet to Sedan beginning December 23. Launching an attack from Neufchâteau, Belgium, on December 30th, the 11th Division defended the highway to Bastogne against a fierce German assault.

The 11th Armored Division, known as the "Thunderbolts," landed in Normandy, France on December 16, 1944. Their first assignment was to contain the enemy in the Lorient Pocket. However, the German Von Rundstedt offensive resulted in a forced march to the Meuse and a focus on defending a 30-mile sector from Givet to Sedan beginning December 23. Launching an attack from Neufchâteau, Belgium, on December 30th, the 11th Division defended the highway to Bastogne against a fierce German assault.

The 11th Division acted as the spearhead of a wedge into the enemy line. Its junction with the First Army at Houffalize on January 16, 1945, created a huge trap for the Germans. After the liquidation of the German Bulge, the Siegfried Line was pierced by Allied forces, and the 11th Division advanced into Germany. Henry was seriously wounded on January 14th during the Battle of the Ardennes while saving the life of a comrade. He was sent to a hospital in Belgium to recover. Henry received a Bronze Star for his valor. His citation reads in part:

Sgt. Smith risked his life to save one of his wounded comrades in his infantry battalion. In the face of direct enemy sniper and small arms fire under enemy observation, Sgt. Smith entered a building containing many enemy to remove a wounded man to safety. His complete disregard for personal safety exemplifies the highest traditions of the military forces of the United States.

During his recovery, Henry may have wondered about his distant German ancestors. He would have been surprised to know that he had come nearly full circle from where his mother's Hartung family had lived before journeying to Russia. The Hartungs were from the cities of Hanau and Büdingen near Frankfurt. In part, they left their homeland in 1766 to escape the incessant warfare in Central Europe. They wanted to live in peace. Yet ironically, here he was nearly 180 years later, fighting a war in his ancestral homeland.

Because of his injuries, Henry could have gone home to Portland, where his injuries and the award of the Bronze Star were reported in the local newspapers. The Mayor of Portland, Earl Riley, sent Anna a personal letter of support and congratulations. Henry had done all that was asked and more. Instead, he chose to return to his friends and comrades in Company C.

As Henry rejoined his company, the 11th Division was poised to cross the Prum and Kyll Rivers. On March 3, 1945, Company C was ordered to secure a bridge over the Kyll River at Oberbettingen. They advanced toward the enemy at 3:00 p.m., crossing the Prum and receiving light resistance from the Germans near Fleringen, where they consolidated with Companies A and B for the night. The attack resumed at 8:25 a.m. the next day against small arms, mortar, and artillery fire. At 4:00 p.m., they seized the high ground near Wallersheim. Company C remained in this position on March 5th, while reconnaissance was made in preparation for an attack to the northeast. The attack was launched on March 6th at 6:30 a.m. through Schwirzheim, Duppach, and Oberbettingen in an effort to capture the bridge over the Kyll River at Oberbettingen. By 5:00 p.m., the U.S. troops had seized Oberbettingen, but the retreating Germans had destroyed the bridge. A bridgehead was established in the face of fierce sniper fire. An enemy counter-attack later in the day temporarily stopped any further progress. Henry could not be located in the fog of battle and was reported as missing in action. His mother, Anna, was notified of the situation by Western Union telegram, creating an anxious situation for the family.

Because of his injuries, Henry could have gone home to Portland, where his injuries and the award of the Bronze Star were reported in the local newspapers. The Mayor of Portland, Earl Riley, sent Anna a personal letter of support and congratulations. Henry had done all that was asked and more. Instead, he chose to return to his friends and comrades in Company C.

As Henry rejoined his company, the 11th Division was poised to cross the Prum and Kyll Rivers. On March 3, 1945, Company C was ordered to secure a bridge over the Kyll River at Oberbettingen. They advanced toward the enemy at 3:00 p.m., crossing the Prum and receiving light resistance from the Germans near Fleringen, where they consolidated with Companies A and B for the night. The attack resumed at 8:25 a.m. the next day against small arms, mortar, and artillery fire. At 4:00 p.m., they seized the high ground near Wallersheim. Company C remained in this position on March 5th, while reconnaissance was made in preparation for an attack to the northeast. The attack was launched on March 6th at 6:30 a.m. through Schwirzheim, Duppach, and Oberbettingen in an effort to capture the bridge over the Kyll River at Oberbettingen. By 5:00 p.m., the U.S. troops had seized Oberbettingen, but the retreating Germans had destroyed the bridge. A bridgehead was established in the face of fierce sniper fire. An enemy counter-attack later in the day temporarily stopped any further progress. Henry could not be located in the fog of battle and was reported as missing in action. His mother, Anna, was notified of the situation by Western Union telegram, creating an anxious situation for the family.

The 11th eventually pushed through the enemy resistance, and Henry's comrades began to search for him and others who were missing after the counter-attack. Henry's remains were discovered near Hillesheim. It was determined that he had been hit by a mortar shell fragment. Anna received another heart-wrenching telegram reporting that Henry had been killed in action. The Smith family was devastated.

On March 23, 1945, Anna received a letter from Brigadier General Holmes E. Dager dated March 23, 1945. The letter reads in part:

On March 23, 1945, Anna received a letter from Brigadier General Holmes E. Dager dated March 23, 1945. The letter reads in part:

Your son was a patriotic American and a gallant solider. He was fighting for the ideas of democracy, peace and security - a fight we who remain shall continue to wage until the forces of war, hate and evil are overcome..... your son was participating in a battle of vital importance to our operations and the zeal and courage with which he fought was an inspiration to his comrades and friends.

Company C continued its march into Germany, crossing the Moselle and Rhine Rivers. The 11th Division seized the city of Hanau, where Henry's 4th great-grandfather, Johann Christoffel Hartung, was born. Allied victory was close at hand. On May 5, 1945, the 11th Division liberated the Mauthausen concentration camp and joined with Soviet Red Army forces on May 8. The end of the Nazi regime was nearing.

The war must have created many conflicting emotions for Henry. Was he a German, a Russian, an American, or a combination of all three? He was undoubtedly a descendant of Germans. The language and culture were part of his family identity. Although his ancestors left their homelands to escape warfare and forced conscription, there was a quiet pride in being German. It was not pride based on nationalism. There was no German nation until 1871, and Hitler's Nazi party was a recent phenomenon. The Volga Germans had no connection to either. The isolation of the German colonists in Russia maintained a strong ethnic identity for generations. They weren't Russians, although small pieces of Russian culture (foods, clothing, language) also shaped them. Henry's parents chose to leave Russia in 1907 because they did not want their children to fight in wars, and they hoped for a better life in the United States. The Russians had just lost a humiliating war with Japan in 1905, which helped trigger the first phase of the communist revolution. The Schmidts feared that the worst was still to come and history would prove them right. Henry was almost certainly aware that in late 1941, the Soviets sent every Volga German man, woman, and child to labor camps in Siberia and parts of Central Asia, effectively ending their distinct culture forever. Despite many conflicting emotions, Henry ultimately chose to fight for his country and American ideals, even though that meant fighting against Germans and the Soviet Union. He knew it was the right thing to do.

Henry was buried with honors at a United States military cemetery in Belgium. His last rites were given by a Protestant Chaplain. Henry was awarded the oldest U.S. military award, the Purple Heart, for those wounded or killed while serving their country.

At the request of the family, Henry's remains were exhumed in 1949 and sent to Portland for burial at the Rose City Cemetery with his father and several siblings.

I was born in 1956, and my parents gave me the middle name of Henry in honor of my uncle. It's a name that I'm proud to have.

The war must have created many conflicting emotions for Henry. Was he a German, a Russian, an American, or a combination of all three? He was undoubtedly a descendant of Germans. The language and culture were part of his family identity. Although his ancestors left their homelands to escape warfare and forced conscription, there was a quiet pride in being German. It was not pride based on nationalism. There was no German nation until 1871, and Hitler's Nazi party was a recent phenomenon. The Volga Germans had no connection to either. The isolation of the German colonists in Russia maintained a strong ethnic identity for generations. They weren't Russians, although small pieces of Russian culture (foods, clothing, language) also shaped them. Henry's parents chose to leave Russia in 1907 because they did not want their children to fight in wars, and they hoped for a better life in the United States. The Russians had just lost a humiliating war with Japan in 1905, which helped trigger the first phase of the communist revolution. The Schmidts feared that the worst was still to come and history would prove them right. Henry was almost certainly aware that in late 1941, the Soviets sent every Volga German man, woman, and child to labor camps in Siberia and parts of Central Asia, effectively ending their distinct culture forever. Despite many conflicting emotions, Henry ultimately chose to fight for his country and American ideals, even though that meant fighting against Germans and the Soviet Union. He knew it was the right thing to do.

Henry was buried with honors at a United States military cemetery in Belgium. His last rites were given by a Protestant Chaplain. Henry was awarded the oldest U.S. military award, the Purple Heart, for those wounded or killed while serving their country.

At the request of the family, Henry's remains were exhumed in 1949 and sent to Portland for burial at the Rose City Cemetery with his father and several siblings.

I was born in 1956, and my parents gave me the middle name of Henry in honor of my uncle. It's a name that I'm proud to have.

Sources

Written by Steven Henry Schreiber, nephew of Henry Smith, on Memorial Day, May 24, 2020.

Letter from Mayor Earl Riley to Anna M. Smith dated March 10, 1945.

Letter from Brigader General H.E. Dager to Anna M. Smith dated March 23, 1945.

Western Union telegram to Anna Smith dated March 29, 1945.

Letter from Major General J.A. Ulio to Anna M. Smith dated April 2, 1945

Letter from Major General Edward F. Witsell to Anna M. Smith dated November 12, 1948.

Press release regarding the Bronze Star awarded to Henry Smith.

Obituary for Henry Smith. The Oregon Journal, 1945.

11th Armored Division Wikipedia page.

Letter from Mayor Earl Riley to Anna M. Smith dated March 10, 1945.

Letter from Brigader General H.E. Dager to Anna M. Smith dated March 23, 1945.

Western Union telegram to Anna Smith dated March 29, 1945.

Letter from Major General J.A. Ulio to Anna M. Smith dated April 2, 1945

Letter from Major General Edward F. Witsell to Anna M. Smith dated November 12, 1948.

Press release regarding the Bronze Star awarded to Henry Smith.

Obituary for Henry Smith. The Oregon Journal, 1945.

11th Armored Division Wikipedia page.

Last updated October 26, 2023