The Steinfeld Family

Heinrich (Henry) Steinfeld was born July 16, 1884, in the Volga German colony of Holstein, Russia. Early in life, Henry learned the family trade of blacksmithing. When the Russian government began conscripting Volga German men for military service, Henry decided it was time to make a life in the New World. In 1902, at the age of 18, Henry arrived in Baltimore on the steamship Gera on March 15, 1902, along with his 13-year-old brother, David (born April 8, 1889, in Holstein). The ship manifest shows that the brothers had last lived in the German colony of Stephan, Russia, and were planning to join a Steinfeld relative in Herington, Kansas.

Henry would later move to Winnipeg, Canada, where he met Barbara Hahn (born February 18, 1889), an immigrant from the Austrian Empire. The two were soon married, and they moved to St. Johns, Oregon, in July 1909, joining Henry's brother David. Henry, Barbara, and David are shown living in the same household at 667 Clinton on the 1910 U.S. Census.

Henry worked as a blacksmith in the North Portland shipyards and laying concrete sidewalks. Barbara raised vegetables, geese, and chickens. Together, they operated a poultry farm in St. Johns at 10006 North Allegheny.

Henry would later move to Winnipeg, Canada, where he met Barbara Hahn (born February 18, 1889), an immigrant from the Austrian Empire. The two were soon married, and they moved to St. Johns, Oregon, in July 1909, joining Henry's brother David. Henry, Barbara, and David are shown living in the same household at 667 Clinton on the 1910 U.S. Census.

Henry worked as a blacksmith in the North Portland shipyards and laying concrete sidewalks. Barbara raised vegetables, geese, and chickens. Together, they operated a poultry farm in St. Johns at 10006 North Allegheny.

Henry and Barbara began a family when their daughter Elsie was born about 1911. The family expanded with sons William (born about 1913), Victor (born about 1917), and Raymond (born about 1922).

When the poultry died from disease, Barbara was motivated to use her experience working at a pickling factory in Canada, and the family fortunes would forever change.

In 1922, Henry and Barbara decided to devote themselves to raising cucumbers and cabbages, which provided the ingredients for their cottage pickling business located on a 4.5-acre site in St. Johns at the intersection of North Allegheny Avenue and North Olympia Streets. With the help of their daughter Elsie Steinfeld Ames and son Bill, jars of pickles and kraut made in their garage were sold door to door for 10 cents a pint or 15 cents per quart.

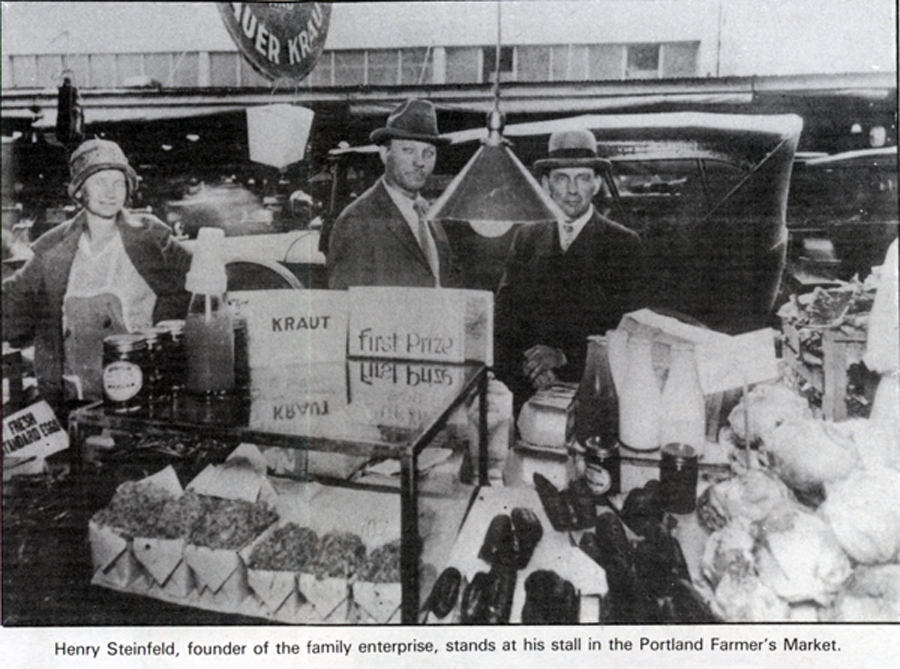

By 1925, with their reputation growing and products selling briskly, Henry Steinfeld opened a stall in the Farmer's Market on Yamhill Street in downtown Portland. The successful Steinfeld's stall was between Fourth and Fifth on Yamhill's north side. Across from their stall was another budding entrepreneur, Fred G. Meyer, who also arrived in Portland in 1909.

Henry and Barbara were successful during the mid-1920s and remained self-supporting through the Great Depression.

When the poultry died from disease, Barbara was motivated to use her experience working at a pickling factory in Canada, and the family fortunes would forever change.

In 1922, Henry and Barbara decided to devote themselves to raising cucumbers and cabbages, which provided the ingredients for their cottage pickling business located on a 4.5-acre site in St. Johns at the intersection of North Allegheny Avenue and North Olympia Streets. With the help of their daughter Elsie Steinfeld Ames and son Bill, jars of pickles and kraut made in their garage were sold door to door for 10 cents a pint or 15 cents per quart.

By 1925, with their reputation growing and products selling briskly, Henry Steinfeld opened a stall in the Farmer's Market on Yamhill Street in downtown Portland. The successful Steinfeld's stall was between Fourth and Fifth on Yamhill's north side. Across from their stall was another budding entrepreneur, Fred G. Meyer, who also arrived in Portland in 1909.

Henry and Barbara were successful during the mid-1920s and remained self-supporting through the Great Depression.

In 1934, Henry leased land along the Columbia River in Scappoose and built bunkhouses for the laborers who worked in the fields to grow the tons of cucumbers and cabbage needed for the business. Sauerkraut was also produced in Scappoose. The family used a Mack truck to haul barrels of pickles and kraut to Seattle and Spokane.

Henry decided to liquidate the company in 1941 when Victor (Vic) received his draft notice. Henry worried that his sons would be drafted and the company would not survive World War II without their help. Later, the family learned that Vic did not pass his induction physical and would not serve in the military. Vic teamed with his younger brother Raymond (Ray) in 1942 to revive the business with a $5,000 loan from Henry.

In those days, all the work was done by hand. Barrels were moved by human power. Shredding the cabbage was often dangerous and tiring, while loading the jars with "kraut" was done with wooden forks. Tin was scarce during the war years, so they began packing the pickles and kraut in glass jars.

Vic managed the plant in St. Johns, and Ray moved to Scappoose to manage the farm and sauerkraut production. The brothers worked 12-hour days, six days a week, with no vacations.

Henry died in 1945 at the age of 61, and the growing business was now firmly in the hands of the next generation.

A pickling plant in Scappoose, previously owned by Hunts Foods, was purchased in 1951 to accommodate demand. Although over 30 small pickling companies existed then, only Steinfeld's would survive. The company diversified into several varieties of sweet and dill pickles, relishes, peppers, and pepperoncini.

Barbara Steinfeld died on January 19, 1976. Three years to the day after her death, the original plant in St. Johns was gutted in an early-morning fire.

Undaunted, the Steinfelds built a new state-of-the-art production and distribution plant in 1980 on a 15-acre lot in the Rivergate Industrial Park at 10001 N. Rivergate Blvd. The business continued to grow, supplying products to nine Western states and several foreign countries.

The business took another blow in 1984 when Vic Steinfeld died. His brother and close working partner, Ray, described Vic's passing as "a very great loss." In 1985, the third generation took over the day-to-day operations, and Ray served as board chairman. Vic's son, Richard, became the company president, and Ray's sons, Ray Jr. and Jim, served as chief executive officer and chief corporation officer. Jane Steinfield-Thomas became vice president in charge of administration.

Steinfeld's celebrated its 70th anniversary in 1992 with the third generation at the helm. At this time, Steinfeld's products were sold in eleven western states and Canada. In 1990, the Japanese market accounted for 4 percent of company sales. The plant in the Rivergate Business Park in north Portland could process as much as a million pounds of cucumbers per day during harvest season, and their sauerkraut facility in Scappoose was the only kraut plant west of the Mississippi.

In 2000, the family made the difficult decision to sell Steinfeld's to Dean Foods Company.

Later in his career, Ray was asked what he valued most in his fellow man. He answered: "Integrity. I like someone I can believe, someone who believes in the value of work. My parents were Christians and taught us the Christian way of life, to treat others honestly and fairly, and to live by the golden rule." For Ray, it was a spiritual bet that paid off. "We didn't set out to be the biggest, just to do our best, be the best we could be."

Henry decided to liquidate the company in 1941 when Victor (Vic) received his draft notice. Henry worried that his sons would be drafted and the company would not survive World War II without their help. Later, the family learned that Vic did not pass his induction physical and would not serve in the military. Vic teamed with his younger brother Raymond (Ray) in 1942 to revive the business with a $5,000 loan from Henry.

In those days, all the work was done by hand. Barrels were moved by human power. Shredding the cabbage was often dangerous and tiring, while loading the jars with "kraut" was done with wooden forks. Tin was scarce during the war years, so they began packing the pickles and kraut in glass jars.

Vic managed the plant in St. Johns, and Ray moved to Scappoose to manage the farm and sauerkraut production. The brothers worked 12-hour days, six days a week, with no vacations.

Henry died in 1945 at the age of 61, and the growing business was now firmly in the hands of the next generation.

A pickling plant in Scappoose, previously owned by Hunts Foods, was purchased in 1951 to accommodate demand. Although over 30 small pickling companies existed then, only Steinfeld's would survive. The company diversified into several varieties of sweet and dill pickles, relishes, peppers, and pepperoncini.

Barbara Steinfeld died on January 19, 1976. Three years to the day after her death, the original plant in St. Johns was gutted in an early-morning fire.

Undaunted, the Steinfelds built a new state-of-the-art production and distribution plant in 1980 on a 15-acre lot in the Rivergate Industrial Park at 10001 N. Rivergate Blvd. The business continued to grow, supplying products to nine Western states and several foreign countries.

The business took another blow in 1984 when Vic Steinfeld died. His brother and close working partner, Ray, described Vic's passing as "a very great loss." In 1985, the third generation took over the day-to-day operations, and Ray served as board chairman. Vic's son, Richard, became the company president, and Ray's sons, Ray Jr. and Jim, served as chief executive officer and chief corporation officer. Jane Steinfield-Thomas became vice president in charge of administration.

Steinfeld's celebrated its 70th anniversary in 1992 with the third generation at the helm. At this time, Steinfeld's products were sold in eleven western states and Canada. In 1990, the Japanese market accounted for 4 percent of company sales. The plant in the Rivergate Business Park in north Portland could process as much as a million pounds of cucumbers per day during harvest season, and their sauerkraut facility in Scappoose was the only kraut plant west of the Mississippi.

In 2000, the family made the difficult decision to sell Steinfeld's to Dean Foods Company.

Later in his career, Ray was asked what he valued most in his fellow man. He answered: "Integrity. I like someone I can believe, someone who believes in the value of work. My parents were Christians and taught us the Christian way of life, to treat others honestly and fairly, and to live by the golden rule." For Ray, it was a spiritual bet that paid off. "We didn't set out to be the biggest, just to do our best, be the best we could be."

Sources

Information provided by Joan K. Steinfeld, Sherwood, Oregon and Richard Steinfeld, Portland, Oregon.

"Success for Steinfeld's is a family dream," by Nancy Strope, food columnist for The Oregonian. Date of publication unknown.

U.S census lists, ship manifests and draft registration cards from Ancestry.com

The Steinfeld Story by Ray Steinfeld, Sr.

"Steinfelds celebrate 70 years of sauerkraut," The Chronicle, Scappoose, Oregon, Saturday, October 10, 1992, pg. 2.

"Steinfeld's family business success beats the odds," The Chronicle, Scappoose, Oregon, Saturday, October 10, 1992, pg. 8.

"Success for Steinfeld's is a family dream," by Nancy Strope, food columnist for The Oregonian. Date of publication unknown.

U.S census lists, ship manifests and draft registration cards from Ancestry.com

The Steinfeld Story by Ray Steinfeld, Sr.

"Steinfelds celebrate 70 years of sauerkraut," The Chronicle, Scappoose, Oregon, Saturday, October 10, 1992, pg. 2.

"Steinfeld's family business success beats the odds," The Chronicle, Scappoose, Oregon, Saturday, October 10, 1992, pg. 8.

Last updated November 18, 2023