People > Our People > John Deering Family

John Deering Family

by Alice Bernice Davison and Richard Davison

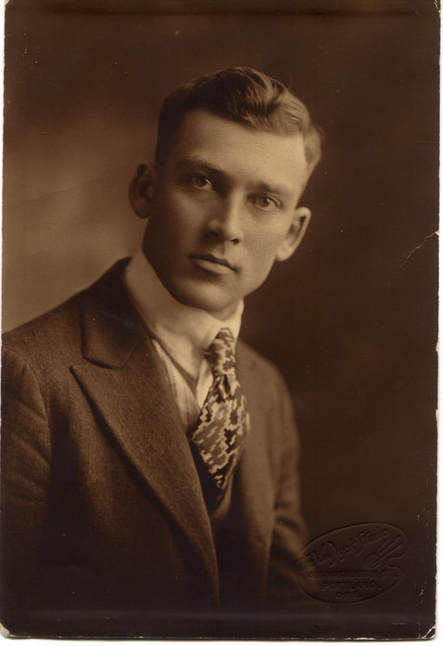

My Dad was John Deering (Johannes Döring). He and his family (father, mother, and two brothers) left Norka, Russia, for the United States in June 1913. Dad's father, Heinrich (Henry), was reluctant to move to America, but the final decision was left to my Dad. At the time of their departure, Dad was nineteen, his brother Peter was eight, and his brother George was four.

They traveled on the steamship Dominion, first to Finland, then to Liverpool, and finally to Quebec, Canada. They took a train from Quebec to Portland via Port Huron and Chicago. During the trip, Dad saw some Finnish people playing accordions, and he was very impressed with the sounds this instrument produced. This explains why I took up the accordion!

During the train ride to Chicago, George was restless and noisy. A woman sitting near the family (an immigrant, too) turned and slapped George. Protecting his brother, Dad slapped the woman back, and the conductor threw him off the train! Because he did not know English, the conductor took pity and had him put on the next train, and he got back together with his parents and brothers in Chicago.

Dad's maternal grandmother, Anna Maria Klaus (née Giebelhaus), and her sister were already in Portland, and they provided the new arrivals with a home to live in. Dad's father lived only nine months in the United States before he sickened and died at 41. When his father passed, Dad became the sole supporter of the family. Initially, he worked in the brickyards during the day and went to school at night to learn to speak and write English and earn his U.S. citizenship papers. Over time, he held several jobs and worked for several companies, including Portland Cement and Portland Cordage.

Dad's maternal grandmother, Anna Maria Klaus (née Giebelhaus), and her sister were already in Portland, and they provided the new arrivals with a home to live in. Dad's father lived only nine months in the United States before he sickened and died at 41. When his father passed, Dad became the sole supporter of the family. Initially, he worked in the brickyards during the day and went to school at night to learn to speak and write English and earn his U.S. citizenship papers. Over time, he held several jobs and worked for several companies, including Portland Cement and Portland Cordage.

In 1919, Dad married my mother, Bernice Marietta King (from Lansing, Michigan), and in 1920, his mother (Anna Elizabeth) married Friedrich Rennich. Rennich had a farm in Vancouver, Washington, and, at the time, was living there with his two daughters, Katherine and Emma. Peter and George stayed with their mother and stepfather, Rennich, living and working on the farm until they finished school. I was born in 1921, and at some point before this time, my mother and father rented Piggot's Castle. I spent my first three years of life in this castle and vividly remember, among other things, our abode and scenes of the Portland landscape from the castle's turrets.

In 1924, there apparently was an economic depression in the Portland area, and Dad lost his job at Portland Cordage. My mother's mother was living in Venice, California, and encouraged my parents to move to Los Angeles, where there were jobs. They decided to make this move, and we traveled to California via a cargo ship during the winter. I remember snow and ice on the ground when we moved and that a sled was used to move our worldly belongings to the ship. I also remember that we encountered rough weather during the voyage. The shipment of lumber the ship was carrying was lost overboard, and we were several days late in arriving at San Pedro.

Dad landed a job with Los Angeles Power and Light digging ditches. He did this work until he obtained his citizenship papers in 1926 when he was promoted to "cable splicer." (At the time, Los Angeles was placing all their power connections underground. Dad was very proud of his citizenship, and being born on July 4th meant a lot to him.) He retired from LA Power after working for them for 35+ years. Peter and George remained in Portland. Peter married Esther Rickman, and they had two boys. George married Pauline Lehl, and they had two girls. I understand that everyone called George "Doc" (I don't know why) and that he and Pauline operated the Milwaukee Sanitary Service.

Dad landed a job with Los Angeles Power and Light digging ditches. He did this work until he obtained his citizenship papers in 1926 when he was promoted to "cable splicer." (At the time, Los Angeles was placing all their power connections underground. Dad was very proud of his citizenship, and being born on July 4th meant a lot to him.) He retired from LA Power after working for them for 35+ years. Peter and George remained in Portland. Peter married Esther Rickman, and they had two boys. George married Pauline Lehl, and they had two girls. I understand that everyone called George "Doc" (I don't know why) and that he and Pauline operated the Milwaukee Sanitary Service.

Dad used to tell me about Norka as he knew it. Here are a few things that I recall him telling me:

It was a very large community, and life was very hard. The winters were cold, and the community had to work in the spring and summer to prepare for the following winter. The families depended on each other, and many things were done in common, such as herding the animals on the steppes during the summer and raising rye, wheat and oats, etc. Each family had their own home, barns, animals, orchards, and garden plots. The church, Lutheran, was very important to the community; It was strict and dominated all aspects of life.

The rivers froze over during the winter and were used as highways. A common mode of travel on these highways was by horse and sleigh. Large hoops of bells were a part of the horse harnesses. Trips to Saratov were made at this time for special things like sugar, molasses, spices, cloth, some clothing, and to trade.

Schooling was limited to reading, writing, and a little math. German was the language that was taught. All children were expected to work with their parents, so school was stopped in early spring and began again when the harvest was completed in the Fall. (Likewise, festivals, parties, and weddings were celebrated in the winter if weather permitted so as not to interfere with planting and harvesting.) The school was held in a single room with wooden benches and tables. The teachers were strict and used switches for discipline. Part of their teaching was from the Bible. Dad obtained the equivalent of an eighth-grade education.

The clothing people wore was very Russian. Boots were made of soft leather. Families would cure hides, tan them, and take them to a local shoemaker with an order of the kind and number of boots and shoes they wanted made. Dad's favorite was a soft, knee-high leather boot. One could also purchase heavy work boots or fur-lined winter boots. Both men and women wore boots. Wool was carded, spun, and knitted into sweaters, gloves, hats, socks, etc. Shirts and clothing of all kinds were made from linen and wool. This material was purchased or traded for. Winter was the time for replenishing clothing.

Feather beds were made for comfort and warmth. Grandmother Deering brought several with her to America. Uncle George and Aunt Pauline gave my husband and me pillows for a wedding present made from grandmother's feather bed.

Fruits and vegetables, such as apples, beets, squash, turnips, and carrots, were stored in a root cellar in large barrels. Cabbage was made into sauerkraut. Other things were pickled, smoked, and put into crocks. A special sausage was made, smoked, and hung in the attic. Part of the chimney was used for smoking the sausage bums. Dad's favorite treat was a chunk of sausage from the attic and an apple from the barrel. (He liked them mellow.) – This he considered a feast. The family jokingly called the sausage "Russian Turkey." (I believe that Aunt Pauline's brothers were still making this sausage at their meat market in Portland in the mid-1980s.) Their bread was like our sourdough bread, and a starter was always kept going.

Cooking was done with coal. Wood was very scarce and was used mainly for smoking all meats. Dad would say bacon would be the width of a hand, from little finger tip to thumb tip. He loved the crispy fat on all meats.

Cows, horses, chickens, geese, and sheep were kept in large barns and sheds during winter. In cold weather, steam from the animals would pour out of the buildings when the doors opened. The stalls were cleaned daily, and the refuse was piled outside. In the spring, this refuse was used for fertilizer and fuel. The fuel was prepared using large forms about two-foot square. They were packed tight with manure and water, then dried in the sun and stored in a dry place. The fuel was used in a furnace fed from outside the house. Large adobe or mud-type pipes were connected to the furnace and ran through the house. These pipes would be warm, and in the coldest weather, the children's feather beds were placed on top of them for extra warmth.

Sources

Photographs and information courtesy of Alice Bernice and Richard Davison. This story was told by Alice Bernice Davison to her son, Richard Davison, and submitted for publication on this website on June 29, 2007. It has been edited for clarity.

Last updated October 26, 2023